3D printing will be huge, in the most boring and fascinating ways imaginable

This isn't another "Look how innovative 3D printing technology is" kind of article. That sort of article has been around ever since the earliest days of additive manufacturing. What makes this article different is that I'll be talking about why 3D printing is poised to move beyond the innovator, into the mainstream.

Many of you may be familiar with the distribution of innovation curve shown below:

Many exciting innovations are born, live, and die in the first two phases of the innovation curve: innovators and early adopters. Some, like Internet-enabled smartphones, blast from years of relative obscurity to dominate the entire curve.

Many ZDNet columnists are innovators and early adopters. I lugged my heavy Altair 8800 onto an airplane (I had to call the airport first and explain what I was carrying). That was my first "mobile" computer. James Kendrick signs his email with "...using mobile devices since they weighed 30 lbs." Jason Perlow, back around the year 2000, showed me a Linux shell running on a handheld Sharp Zaurus (which made me giddy in that unique way that seeing the Linux shell running on something unexpected makes certain geeks giddy).

But these innovations didn't reach the mainstream overnight. The Sharp Wizard came out in 1989. Microsoft tried to get mainstream adoption with tablet computing years before Apple. I bought a (terrible) Acer tablet PC back in 2002, a full eight years before the first iPad.

All this brings us back to 3D printing.

There is no doubt 3D printing is both practical and transformative. Costs are coming down, extrusion materials are becoming more varied, and projects range from an entirely 3D-printed R6 droid to giant 3D printers producing houses.

There is a problem with the innovator curve shown above. Some technologies don't make it out of the first two bands. And here's the dirty little secret of those two bands: they're not mainstream. If your product is stuck in the early adopter phase, you might have a nice small company. But you will never blast past the billion dollar mark. Look at how far mainstreaming of technology has taken Apple. Their profit last quarter eclipsed Microsoft and Alphabet (Google) -- combined.

Solar energy is one such problematic technology. We all agree that solar should be a winner. I mean, seriously, how bad can free energy be? But the problem with solar is that it costs too much and is too generally unreliable and cumbersome to be a win for everyone. Here in Florida, I have a neighbor using solar to heat his pool. But he still connects to the grid for everything else.

Solar was stuck in the early adopter phase for years. Some of our super eco-conscious friends have wanted solar for decades, but it's only been in the last few years that the technology and price point have made it clear there would be ROI for them to go for it.

3D printers have been adopted by hobbyists and "makers," industrial designers, product engineers, medical practitioners, and artists, to name just a few professions. But so far, 3D printers have not been adopted as just another piece of office equipment. I believe that's about to change.

A long time ago, I spent $6,000 (in 1980s dollars -- about $12,000 to $20,000 in today's value) for an Apple LaserWriter. I recall also buying a LaserWriter Plus. Those were the early days of desktop publishing. Now, today desktop publishing has been overtaken by the Web, but back then, the idea that a small business could produce its own marketing materials -- on demand -- was transformative.

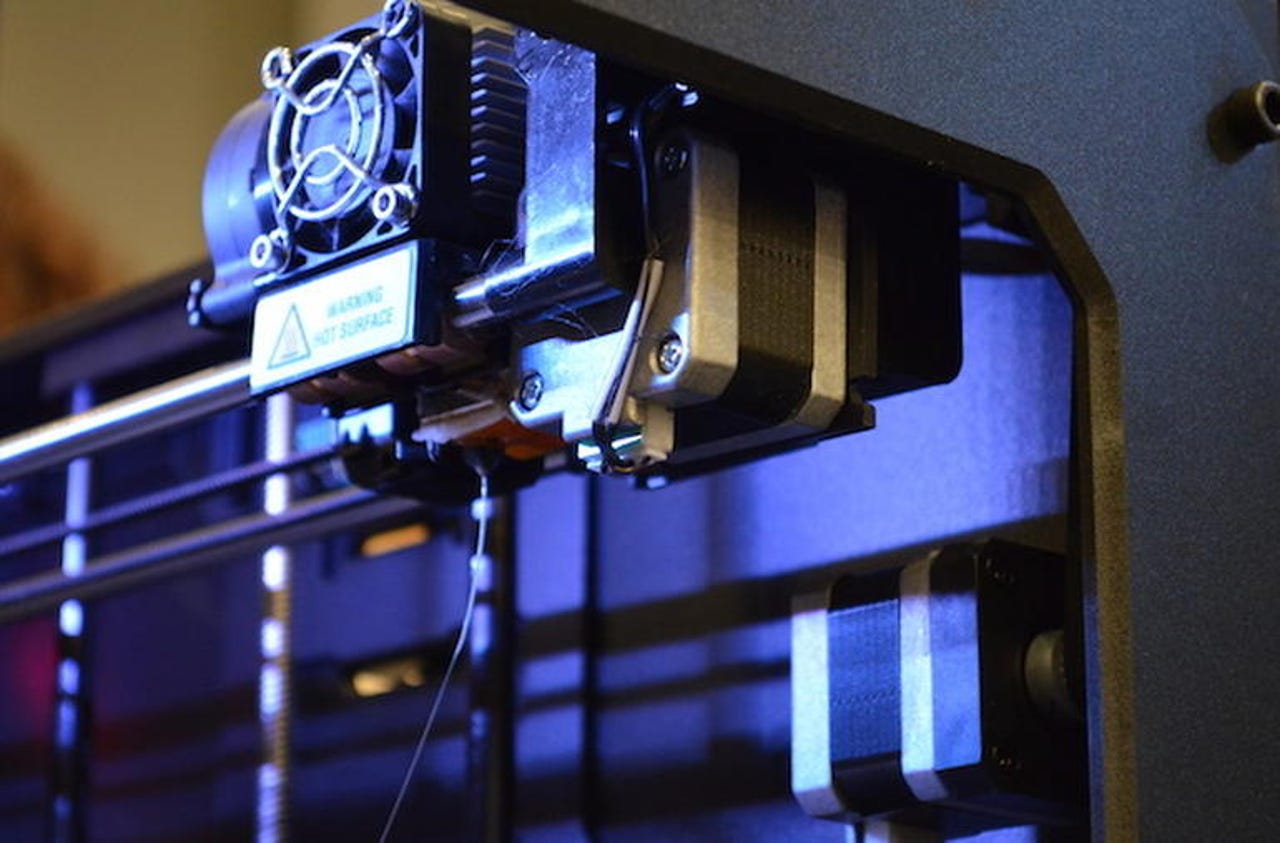

Gallery: Stratasys 3D printer

Not only was it transformative, it was equalizing. Small companies (like mine) could produce marketing materials that looked as good as those produced by much bigger companies. And we could produce those materials much faster. The result was we were able to get into markets that would normally have been closed to small companies.

Desktop publishing bypassed the print shop. It bypassed the typesetter (a person who hand cut out type and pasted it up for production). It bypassed the photo lab. And it warped time, allowing us to shrink time-to-presentation by weeks and months compared to the older process. And while each individual piece produced was slightly more expensive than the per-unit cost when printed the old fashioned way, we didn't need to produce that many, and so the savings more than covered the cost of the printers.

This is where I see 3D printing going. 3D printing will enable anyone to make small, helpful objects. While creative desktop publishers pushed the limits of the hardware (we certainly did), creative 3D printers will do the same. But the bulk of desktop publishers produced regular stuff: flyers, brochures, manuals, and so on.

3D printing will do the same. 3D printing will let you look at a need and fill it. Let's say you have an odd arrangement of light switches on your wall, for which there is no commercial cover that would look good. Design, and then 3D print one.

Or let's say you need a little box that hangs just so off of the back of a TV to hold a hidden set top box. 3D print one. Or let's say your boss is constantly complaining about having no reasonable place to hook his bluetooth ear jewelry. Design a small stand and print it on the 3D printer.

Or let's say your wife bought a pair of popcorn forks (yeah, they exist, but they're terrible) and she wants you to make a new set that works according to her preferences and specifications.

Buyers could choose to use 3D printing for kids craft projects, to help customize kitchen utensils, to create containers and stands for office needs, to create battle armor for your cat.

All of these are viable 3D printing projects. The possibilities are endless.

The point is, in order to cross the chasm from early adopter to early majority, 3D printing has to move from visionary and innovator to pragmatist. The real compelling mainstream business case for 3D printing is creating new products.

We've seen the start of this. The incredible growth in crowdfunding would not have been as compelling if entrepreneurs weren't able to use 3D printing to build tangible prototypes. And 3D designers wouldn't have had as much hope for their eventual success if they all had to go through the very restrictive and often-impractical venture funding route.

Bite Silicon Valley: 3D printed confections with ChefJet Pro

Look at what YouTube and smartphones did together. Sure, there were digital video cameras. But distributing video online was costly as heck. YouTube came on the scene just a year or so before smartphones starting taking off, and they fueled each other. Today, there are individuals -- like James Bruton, the guy 3D printing the R6 droid and a giant animatronic Hulk Buster suit -- who have hundreds of thousands of viewers.

But while 3D printing has had a lot of life in the Kickstarter community and other maker communities already, more and more people will be able to see the ability to create products, create objects, and design objects for others as a new and viable way to make a living.

In reality, there's often relatively little difference between an innovator and a member of the buying majority. While skill and education often differentiate innovators and early adopters (those who can figure out how to use the innovations), it's really often about bottom line. Before 2008, there were millions of programmers. But now everyone wants to create an app because they think that's their ticket to riches.

Innovators often want to use the technology to use it and to figure out what they might be able do with it. The chasm jump happens when mainstreamers see an obvious tangible benefit and a relatively low barrier to entry.

But for 3D printing to cross the chasm, mainstream buyers not only have to see applications (or realize that they can make things they previously just tolerated not having), but also be able to afford the gear, and be confident they have or can develop the skills to use the technology.

All three of those criteria have been difficult for 3D printing. Price is easy. It's coming down rapidly. But good 3D printers are still in the few thousand dollar range and that will squelch adoption, at least for a while.

Envisioning uses is still hard for the early majority because it takes a new mindset to realize that if you need a part or a fixture or a fix, you can actually draw it on your computer and generate it in the physical world.

But the third barrier is the skills barrier, and that one still has some challenge. Many people have absolutely no experience with CAD (computer aided design) -- or design for that matter -- and thinking in 3D space takes some getting used to.

A lot of people will say that CAD is hard, and they just don't have the skills or design ability to create the 3D models you need to feed into 3D printers. For complex projects, that's true. But here's the thing. There's a lot you can build out of simple rectangles.

Because of rectangles, I think the skills hurdle to adoption can be overcome. Here's why.

If you can select a few files on screen by drawing a rectangle around them, you can do CAD. There is an amazing amount that you can build by combining rectangle-shaped objects. The entire knock-down furniture business is built on the idea that rectangle-shaped slabs can be combined into many wonderful and useful variations.

Build some box shapes. Cut out some holes in them. Build some more box shapes. Pretty soon you have a unique holder or object that can make your life easier, solve a problem, or save time.

You can get very basic 3D printers for just a few hundred dollars -- about the price of a good inkjet printer or today's laser printers. There are service bureaus that will take designs and print them for you. There are Makerspaces all across the world where you can gain shared access to a 3D printer.

Even Staples offers a 3D printing service in some stores. If that doesn't help prove my case that 3D printers will become common office equipment, nothing will.

3D printing is not commonplace -- yet. Back in the 1980s when my company invested in laser printers, they were still quite costly. Today, you can buy a laser printer for about 2 percent of what one cost thirty years ago.

3D printers are fascinating. They're as close to the idea of the Star Trek replicator as we're likely to see in our lifetimes. Experimental 3D printers have printed pizzas, bio matter, and prosthetic devices. You can buy a chocolate-making 3D printer right now. 3D printers have even saved lives.

By combining the Internet (and 3D design marketplaces like Thingiverse), someone in one part of the world can design a physical object, and someone on the opposite side of the planet can make it appear. So, in a way, 3D printing is also a bit like the Star Trek transporter (without the scary dematerializing and rematerializing of molecular matter).

Crowdfunded 3D printer innovations

The future of 3D printing will not be all about industrial designers and artists and tiny little R2D2 replica figurines -- although, to be sure, that's been a big part of the birth of 3D printing. Instead, the future of 3D printing will be as dull and prosaic as office equipment and as incredible and amazing as the human mind can imagine.

By the way, I'm doing more updates on Twitter and Facebook than ever before. Be sure to follow me on Twitter at @DavidGewirtz and on Facebook at Facebook.com/DavidGewirtz.