AGD releases critical infrastructure national security Bill

Australia's Attorney-General's Department (AGD) has published its exposure draft for the Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017, which contains a "last resort" provision enabling ministers to direct companies to conduct risk mitigation actions.

The Bill was designed for the purpose of increasing the federal government's capacity to manage national security risks arising as a result of offshore and overseas involvement and control over infrastructure.

"Foreign involvement in Australia's critical infrastructure is essential to Australia's economy. However, with increased foreign involvement, through ownership, offshoring, outsourcing, and supply chain arrangements, Australia's national critical infrastructure is more exposed than ever to sabotage, espionage, and coercion," Attorney-General George Brandis said in a statement on Tuesday morning.

This last resort power would be used for "critical assets in the high-risk sectors when a significant national security risk cannot otherwise be mitigated", AGD stated in the Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017: Explanatory Document [PDF].

Existing powers in some jurisdictions that already allow for ministers to give directions to a critical infrastructure owner or operator are limited to being "generally only triggered in the case of an emergency event", the document explains.

Under Section 30 of The Security of Critical Infrastructure Bill 2017 exposure draft [PDF], the minister is permitted to give a reporting or operating entity of a critical infrastructure asset "a written direction requiring the entity to do, or refrain from doing, a specified act or thing".

The last resort power can only be used where there is a "significant" national security risk; the reporting entity or operator has not implemented risk mitigations; and there are no federal, state, or territory regimes that could be used to enforce risk mitigation strategies.

The minister is required to give primary consideration to a mandatory Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) adverse security assessment to consider the risk and recommend an action; be satisfied that "good faith" negotiations have taken place with the entity; consider the costs and consequences of implementing the mitigation strategy on an entity's competition and customers; and ensure the direction is "reasonably necessary for purposes relating to eliminating or reducing the risk".

Under s31, the minister must consult with the relevant state or territory minister and with the entity before giving a direction, with a civil penalty of 250 penalty units specified for entities that do not comply with the directions (s32).

In terms of the regulatory burden of the last resort power, the explanatory document outlines four separate scenarios and their potential costs.

"Across the four scenarios, it is assumed that a direction will only be used once every three years," the explanatory document says.

"Each scenario has been assigned an equal probability of 25 percent; within each scenario, the 25 percent probability is split between the 12 entity types (small, medium, large by electricity generation, electricity transmission/distribution, ports, and water), and a medium and a large entity is twice as likely to be issued a direction than a small entity."

Scenario 1 depicts a direction to move and store all corporate and offshore data to an Australian Signals Directorate (ASD)-certified cloud services provider, which it estimates to cost AU$396,655 across electricity, water, and ports sectors annually, with one-off costs ranging between AU$64,155 for small electricity generation and AU$1.5 million for large electricity transmission/distribution entities.

Under scenario 2, a business would be directed to limit offshore access to industrial control systems unless approved by government, with an annual compliance burden of AU$67,955 and one-off costs of between AU$51,099 for large electricity generation and AU$129,932 for small electricity transmission/distribution.

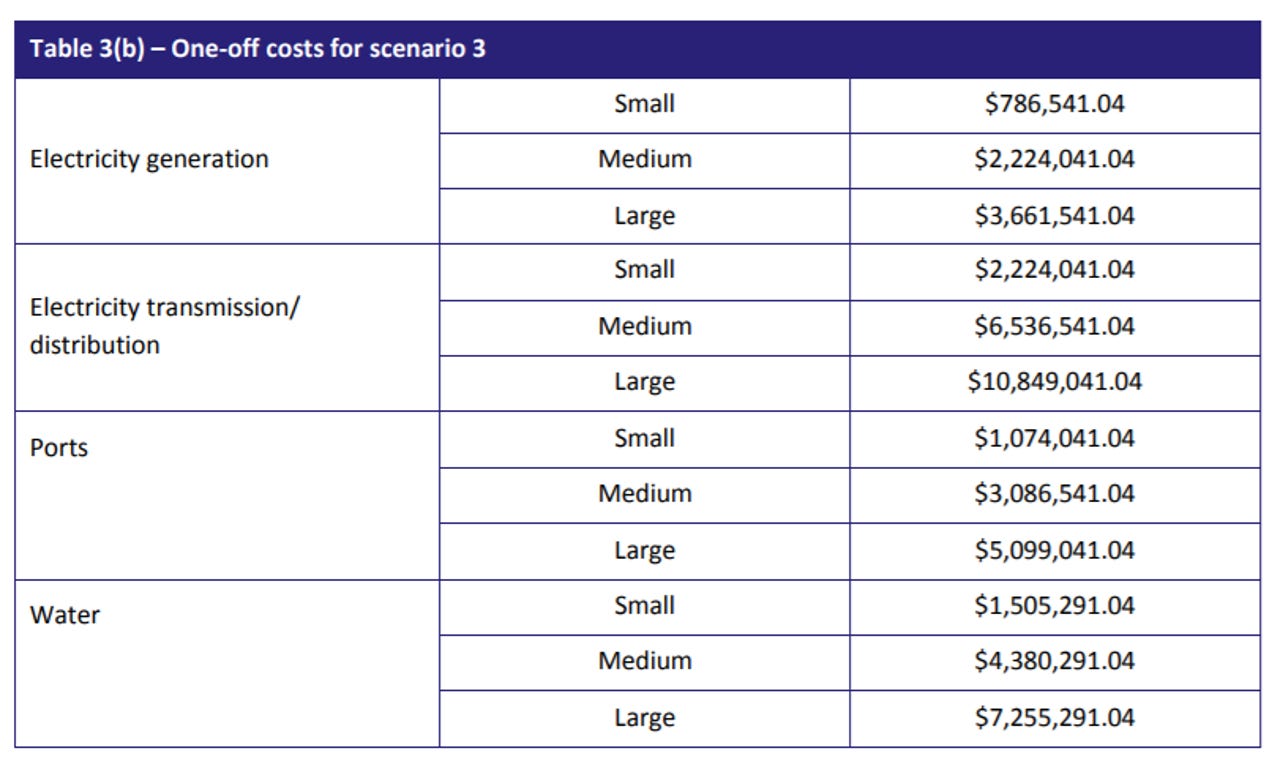

Scenario 3 would see the government preventing a business from outsourcing core network operations, with an annual compliance burden of AU$3.82 million and one-off costs ranging between AU$786,541 for electricity generation and AU$10.8 million for large electricity transmission/distribution.

Lastly, scenario 4 involves a government direction preventing a business from sourcing core operational systems technology from low-cost and less-secure providers, with an annual compliance burden estimated at AU$5.09 million and one-off costs of between AU$74,928 for small ports and AU$34 million for large electricity transmission/distribution.

"The total annual expected regulatory burden, averaged out over each scenario, sector, and entity size based on the assumptions above (including using the power once every three years) and across a 10-year costing timeframe, is AU$9.38 million," the explanatory document says.

"It is unlikely that such a power could be used to mitigate all possible national security risks, such as an identified risk of espionage."

The government's Critical Infrastructure Centre (CIC), launched in January, already works across electricity, water, ports, and telecommunications to conduct national security risk assessments and make suggestions for mitigation strategies.

However, the government said it currently has a limited capacity of understanding which entities own, control, and have access to critical infrastructure, as this information is commonly treated as commercial-in-confidence and thereby not shared.

Stressing a need for collaboration between industry and government to manage critical infrastructure risks, the Bill therefore also vests in the AGD secretary the power to form a critical infrastructure assets register and collect interest and control information.

"Ownership interests are often held in complex corporate structures, spanning multiple jurisdictions, or through trusts, managed funds, or nominee companies. Further, while ownership is an important aspect, the degree of control and access through outsourcing and offshoring arrangements can also be difficult to establish, as they are often detailed in complex contractual arrangements," the document explains.

"The government needs to be able to identify and respond to the full range of national security risks in a way that provides flexibility to respond to changes in the geopolitical landscape as it evolves."

Under s35, the secretary may take and retain for as long as is necessary any documents produced by affected entities, and make copies of such documents.

"The secretary must keep a Register of Critical Infrastructure Assets, containing information in relation to those assets," Section 17 says.

"The responsible entity for a critical infrastructure asset must give the secretary operational information in relation to the asset. An entity that is a direct interest holder in relation to a critical infrastructure asset must give the secretary interest and control information in relation to the entity and the asset."

Entities must report the required information within six months of the legislation's commencement, and must notify the government of any changes to this information within 30 days of the change being made under threat of a civil penalty of 25 penalty units.

The Bill would regulate around 100 critical infrastructure assets across "the highest-risk sectors" of electricity, ports, and water (s9).

Critical water assets are defined under the Bill as being water and sewerage infrastructure that services at least 100,000 connections and provides collection, production, filtration, treatment, storage, conveyance, or reticulation of water and sewage; while critical electricity assets are networks, systems, or interconnectors for the transmission or distribution of electricity, or electricity generation stations that are critical to the security and reliability of electricity networks or systems in a state or territory (s10).

The ports specified under s11 are the Port of Darwin, Port of Geelong, Port Adelaide, Port of Rockhampton, Port Botany, Port Hedland, Port of Brisbane, Broome Port, Port of Cairns, Port of Christmas Island, Port of Dampier, Port of Eden, Port of Fremantle, Port of Gladstone, Port of Hay Point, Port of Hobart, Port of Melbourne, Port of Newcastle, Port of Townsville, Port of Sydney Harbour, and any security-regulated port.

"If any of these assets were disrupted, they would have a significant impact on Australia's economic interests and services for large populations," the explanatory document says.

"Direct interest holders of a critical infrastructure asset will be required to provide interest and control information in respect of the asset. Responsible entities for a critical ... will be required to provide operational information, such as system access abilities and operator and outsourcing arrangements."

The CIC is to maintain a "secure web portal" for the reporting of this information by entities, it said, with s21 adding that the secretary must ensure the register is not made public.

According to the government, the register would "impose a minimal compliance burden on industry".

The government is accepting submissions on the Bill until November 10, asking for feedback on nine issues, including whether gas, datacentre, and other critical assets should be included in the legislation; whether the Bill sufficiently safeguards against the directions power being exercised as anything other than a last resort; whether the costings are accurate; and whether there are barriers for companies to provide information or cooperate with the government.

Macquarie Government, part of the Macquarie Telecom Group, welcomed the legislation and said it is necessary to force private companies to comply with the same guidelines that government agencies operate under.

"Much of the infrastructure that allows us to operate in our day to day lives -- power, communications, water, transport systems -- are privately owned, and all are completely dependent on information and communications technologies to work," Macquarie Government managing director Aidan Tudehope said.

Earlier on Tuesday, when announcing that the government would be looking to recruit those working within infosec for the banking and telecommunications sectors to fill out its Cyber Reserve force, Minister Assisting the Prime Minister on Cyber Security Dan Tehan said the AGD's draft legislation is being created for potential use, as he cited no historical cases where it might have been used.

"A hit on a power grid can have catastrophic implications for that country, and unfortunately we've seen state actors use that in the past," Tehan said.

"We want to make sure here in Australia, we're doing everything we can to keep our critical infrastructure safe."

The government in September similarly passed the telecommunications national security Bill, with the Telecommunications Sector Security Reforms (TSSR) to establish a framework for national security threats within the telco industry.

Brandis and Communications Minister Mitch Fifield in August said the TSSR has an emphasis on "the shared responsibility between government and the telecommunications industry".