Bus companies prosper amid protests in San Francisco

On a recent morning, I climbed onto my bike to ride to work, pedaling through a chilly San Francisco morning down 24th Street in the Mission District.

Descending the street’s steep hill and taking in the view east toward the Bay, I saw an armada of white double-decker buses with tinted windows that filled the street in front of me.

I coasted past a municipal bus stop at Valencia street, where a gaggle of people staring at their mobile devices climbed aboard the vehicle with the electric sign “GBUS to MTV” in the window. As the people disappeared inside, a city bus idled impatiently behind the much larger private one. Horns honked, drivers’ faces reddened.

A couple of weeks later at the same bus stop, a group of “anti-gentrification” protesters blocked the so-called “Google bus” until the cops came and moved them away. The group held signs voicing anger about rising rents and evictions in the city and blamed the technology and biotech companies that employ the shuttles for the problem.

While private employee shuttles have been operating in the city for nearly a decade, their use has grown by leaps in recent years as more technology workers have moved to San Francisco from Silicon Valley. The massive, Wi-Fi enabled shuttles have become as ubiquitous in the San Francisco cityscape as cable cars, creating what transportation officials say is a bus fleet the size of a medium-sized city’s public transit system.

Yet, as old and new residents debate the shuttles’ role in widening the gap between rich and poor and raising rents, the phenomenon has been a boon for one of the city’s traditional blue-collar employers – the shuttle bus industry – at a time when it has come under threat from companies like Uber and Lyft, which has also changed the way city folks get around.

A Cottage Industry

Amid the kerfuffle, shuttle companies are hiring drivers, mechanics and support staff needed to run a growing enterprise.

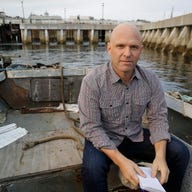

“It’s been a good business,” said Gary Bauer, founder and CEO of Bauer’s Intelligent Transportation, which started working with Google in 2005 with 10 shuttles.

Now Bauer’s IT is running 53 shuttles for tech employees. Google alone now operates 100 buses throughout the Bay Area, according to a University of California, Berkeley study.

Genentech, the biotechnology company, started its own shuttle service as a way to improve recruitment, reduce parking costs and reduce its land use in a region where real estate is at a premium.

By 2012, according to the UC Berkeley research, nine technology companies including Facebook and Apple had followed Google’s lead, shuttling people between San Francisco and Silicon Valley.

In San Francisco there are now 35,000 separate boardings each day for shuttles moving both in the city and out. About 7,000 shuttled daily between the city and Silicon Valley, according to the study.

“It keeps my drivers employed, keeps my mechanics employed,” Bauer said. “We now have 430 employees.”

Yet as the private bus bonanza has ballooned, so have protests and, in at least one case, violence. One Google shuttle in Oakland had its window broken out as it tried to take employees to work.

“People call them the Richie Rich buses, but that’s not the way it is,” Bauer said of the class warfare. “These people are concerned about the environment and congestion on city streets. This whole thing has been misconstrued ... I think it’s a positive thing for everybody. It definitely is a growing opportunity for people getting to and from work, and we’ve got to look at ways of reducing pollution.”

TECHIES vs. ANTI-GENTRIFICATION PROTESTERS

The mathematics of the shuttle debate appear simple: Bauer says each of his buses holds 56 people, which he says removes the same amount of cars from the road. With dozens of shuttles running each day from just this one company, that’s hundreds of fewer cars. Expand it out, and each day in San Francisco traffic is a little better, the air a little cleaner.

It’s good for the environment and traffic. What’s not to like?

Well, everything, according to the bus haters. First, anti-shuttle people say the enormous buses are often not full, and that many of the employees who do use the gas-guzzler buses would otherwise ride their bikes or take mass transit.

They say the free transportation also allows wealthy tech employees to live further from Silicon Valley, increasing city congestion, not improving it, and driving up rents in the process.

David Campos, a San Francisco supervisor who represents the Mission District, said tech workers should not be demonized, but that more needs to be done to address a problem that has affected his area.

“Not vilifying the tech workers doesn’t mean we don’t have a real and frank conversation about the impact these shuttles are having,” Campos said during a speech recently.

No one is denying that the increase in the massive vehicles on the old city’s narrow streets has caused a problem.

“The commuter shuttle sector has grown very rapidly and it’s created an impact on (San Francisco’s municipal buses),” said Carli Paine, a transportation planner with San Francisco’s Municipal Transit Authority who is working on the city’s new regulations. “Muni can’t get to the curb in loading and unloading passengers, which causes impacts of localized congestion, (and in some cases caused) bike riders to veer out of the bike lane into mixed flow traffic.”

Still, Paine said the effects are not being seen at every bus stop used by the tech shuttles, but that they have verified areas where congestion is a problem.

SEEKING DATA

As debate has raged over the pros and cons of the shuttles, each side has sought ammunition to prove its argument. The buses and their drivers work in a challenging environment, with blockades and protests becoming common.

A lack of data and research on the issue has stoked the flames in some ways, with each side making claims about the benefits and downsides without much to back them up.

Yet a recent study from UC Berkeley released in January set out to answer some key questions. Graduate students Danielle Dai, a transportation engineer, and David Weinzimmer, who studies city and regional planning, passed out slips of paper at nine bus stops with a Web address linking to a survey. The researchers received 130 valid responses from tech company employees.

Dai and Weinzimmer asked what the employees would do if shuttle buses were discontinued, and the results seemed to provide ammunition data for both sides.

On the pro-shuttle side, 48 percent said they would drive alone to work. “The data shows that nearly half of current shuttle riders would drive alone if the shuttles were not provided, supporting the positive impacts of the shuttles on environmental and congestion reduction goals,” according to the study.

“On the other hand, since 20 percent say they would use public transit were the shuttles not available, the shuttles do have an impact on public transit ridership and finances.”

For the shuttle haters, the study found that 40 percent said they would move closer to work if shuttles were unavailable.

The researchers concluded that the shuttles do “exacerbate the jobs-housing imbalance by enabling individuals to live farther from work.”

GROWTH CHALLENGES

Like every burgeoning new business, shuttle companies in the Bay Area will have new costs associated with increased regulation and providing amenities to people used to a high level of coddling.

San Francisco recently passed first-in-the-nation regulations to help rein in what one supervisor called the “Wild Wild West on our streets.”

The new rules will charge the companies $1 per stop, which could amount to about $100,000 or more for a company like Google or Apple. The city also set aside 200 bus stops that can be used by the shuttles – they’ll face tickets if they use non-designated stops.

While the new rules were hailed by some as a first step in the right direction, they angered others who say the tech firms have been getting away with breaking the law for far too long.

Angry city bus riders who pay $2 a ride said at a recent public meeting that the tech firms were getting off too easy. And non-mass-transit drivers who pay $300 per ticket for parking at a city bus stop asked transportation officials why the companies weren’t also being cited.

A woman who addressed city transportation officials at a recent hearing on the shuttles said she got a ticket for dropping her husband off at a bus stop recently, even though tech shuttles were doing the same thing for free.

“It wasn’t a $1 ticket for one stop, it was more than $100,” she told the officials. “That’s the way regular citizens in San Francisco are treated if they’re unlucky enough to be spotted by a meter man.”

Bauer and the technology companies are supportive of the city’s new rules, saying it’s time the two worked together to streamline this new transportation system.

Another challenge of quick growth is providing enough tech support for the massive demand on each bus ride. As ridership increases, shuttle bus owners aren’t having a problem finding more vehicles or drivers. They’re trying to keep up with the high-speed Wi-Fi demands of their multi-gadget-using clientele.

“The average person has two or three devices. It’s a phone, a computer and an iPad, if it’s not also your watch and your glasses,” Bauer said, referring to Google Glass users. “That’s a major drain on bandwidth, and Wi-Fi is a draw (for riders). To keep up with that has been a challenge in our industry.”

With these kinds of challenges and a city amenable to making it work, the economic picture for shuttle companies in the San Francisco Bay Area seems bright. It remains to be seen if the protests will continue.

“I don’t get the downside,” Bauer said. “If you’re taking cars off the road and reducing the pollution everyone’s concerned about with climate change, I’m not understanding the downside.”

Photo: Flickr/CJ Martin

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com