Can open source and open systems really open the door to healthier democracies?

Civiciti, a new tool for civic participation, was recently presented in Barcelona, but some urban authorities in Spain prefer to develop their own open-source software.

Many think technology can improve democracy and good governance. Open data and online platforms allow the public to participate more directly and gain greater transparency and accountability.

This whole area of technology for improved governance could be worth $2bn over the next decade, according to Pablo Sarrias, CEO and founder of OpenSeneca.

His company was set up by Telefónica Open Future and Barcelona-based electronic voting company Scytl, which has provided proprietory election technology for the 2016 US elections, among others.

But given the high cost of using technology to enable the public to participate more directly in political processes, is it really worth the effort?

Sarrias thinks that at the very least participatory platforms can foster "a constructive dialogue", unlike social networks where "robots and trolls can poison certain initiatives".

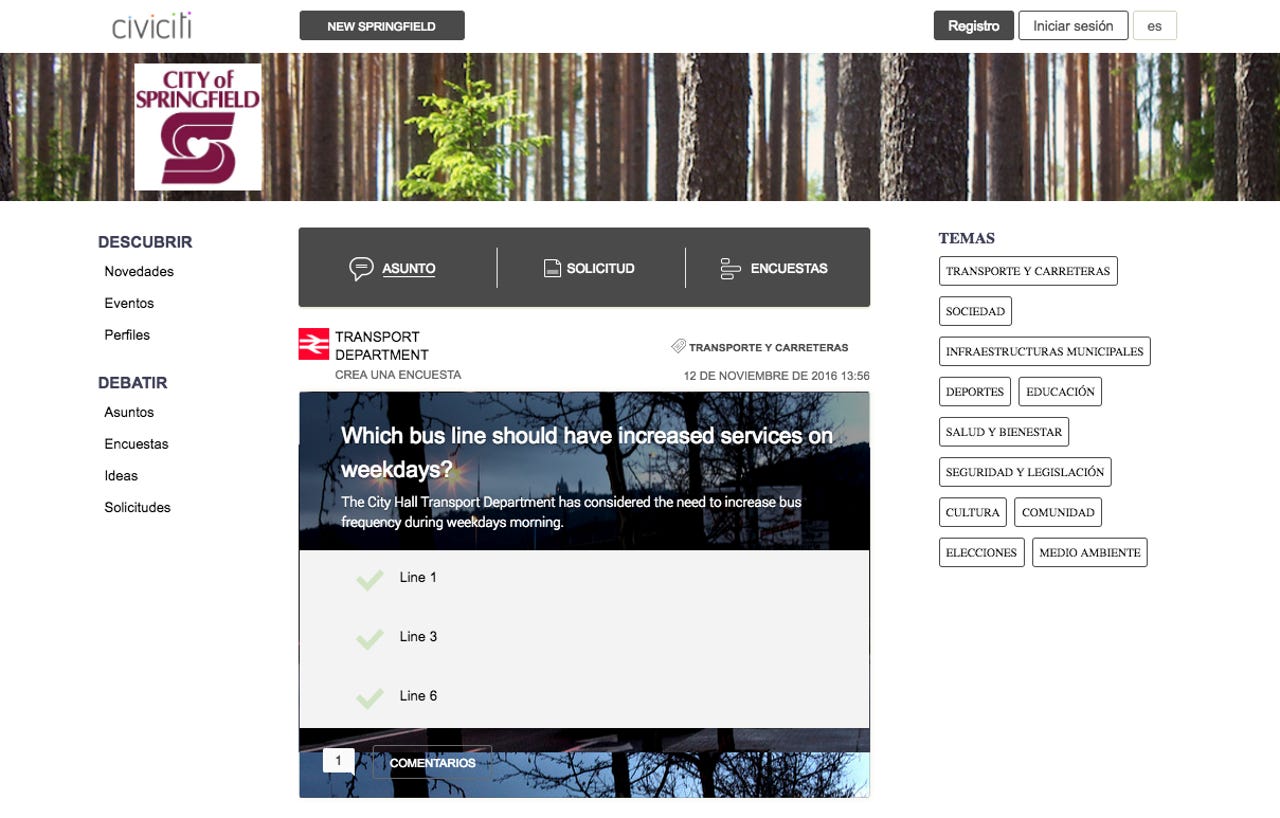

At the recent Smart City Expo World Congress in Barcelona, OpenSeneca officially presented its civic platform Civiciti, which enables participation, consultation, and debate between local authorities and citizens.

The cloud service uses an open-source framework and a freemium business model to foster "continuous democracy". It features a gamification system that encourages users to participate, as well as a tool to facilitate data comparisons.

OpenSeneca's CEO acknowledges that attempts to build public participation programs have often encountered "political, operational, and social hurdles".

In Barcelona, the most notorious example was the consultation over the arterial road of the city, La Diagonal, conducted by Indra and Scytl, which attracted a very low level of public participation with only about 12 percent of potential voters taking part, and was seen as a major failure for the city's mayor, Jordi Hereu.

Nevertheless, Sarrias believes that, "a platform that's not perceived as a mayor's personal gadget, which brings good practises and allows moderation and audit, can help grow participative democracy".

Telecoms specialist Sarrias, who's been involved in e-voting projects worldwide, says Civiciti provides an "open and secure communication channel that facilitates open government".

The system plans to reach 500 million users within the next 10 years. It already has customers in Spain and India and is working on agreements with five countries in South America, as well as conducting pilot tests in Canada.

At the conference, the mayor of Jun in Granada, Spain, José Antonio Rodríguez Salas, and Francisco José Santana Pérez, general director of new technologies and telecommunications at Las Palmas de Gran Canaria city council, showcased their experiences with the platform.

Santana highlighted that they got 75 "great ideas" from the public since launching the platform in July. That may not seem such a large number but he says, "first, we need to teach citizens how to participate".

Ricard Faura, head of knowledge society at the Catalan government, took a similar line, arguing that the technology and the platforms are not the issue.

"The problem is getting a real participation. We must inform the main actors involved in the participatory process to raise awareness and mobilize as many citizens as possible. In parallel, we should facilitate access, education and citizens' empowerment to extend the scope of the process," he said.

Meanwhile, Barcelona and Madrid have gone their own way and developed their own open-source software to foster participation.

The reason for this decision is quite simple, according to Xabier Barandiaran, project leader of Decidim.Barcelona, Barcelona's open platform for participation processes.

"Closed solutions don't guarantee privacy and integrity of data. They can't be adapted to specific necessities and can't be shared with other cities," he said.

Barcelona city council has conducted several participation processes to decide on the focus for the municipal and district action plans and where the money should be spent. More than 39,000 people brought more than 10,000 proposals to the programs, 72 percent of which have been included in the final documents.

Furthermore, in late November, it organized a singular participation process to decide on the future direction of the platform.

"It originally looked like the one in Madrid, but in January 2017, we will issue a new version of Decidim, which will be totally adapted to the Barcelona citizens' concerns and desires," Barandiaran says.

"The internet has gone through various stages and we, at Barcelona city council, are convinced that it has to enable connecting people with binding political capacities to foster collective intelligence and promote social action."

Smart City Expo World Congress director Ugo Valenti thinks that more critical than having participation platforms that actually work is having citizens who are willing to participate.

"Engagement is the most critical element in this equation and to achieve it we're going to need a cultural shift, and those are even more difficult to achieve than technological ones," he says.

Barcelona is still near the top of the rankings of smart cities in the world. The Catalan capital, with 84 percent of companies in this sector in Catalonia, is the second smart city in the world after Singapore, according to Juniper Research.