Cheat Sheet: The internet of things

It's gonna get physical...

The internet of things, you say? Sounds like an oxymoron to me.

The internet of things - or IoT for short - is all about bringing the analogue (physical) world into the digital (virtual) sphere so that physical objects can be identified, tracked, located and even controlled online, in real-time.

And what does the IoT mean? Lots and lots more lovely data.

Tell me more...

IoT describes a not-so-far-distant future reality towards which our increasingly wired and sensor-strewn society is accelerating.

There are many names for this already: other terms you may have come across include: ubiquitous computing (or ubicomp), invisible computing, pervasive computing and even - somewhat inevitably - web 3.0.

The gist is: couple ubiquitous wireless and cellular networks with everyday objects that have wireless sensors embedded in them et voila: there's your internet of things - smart objects that can be identified by the tiny chips they contain.

What kind of chips/sensors are we talking about?

RFID - radio frequency identification tags - for one; mini chips that can transmit data via radio. Passive RFID chips draw power from a RFID reader, meaning they don't have to rely on batteries either.

Of course the world contains plenty of 'smart objects' already - obvious examples include your wireless-enabled laptop and the smartphone in your pocket. Rather more weird and wonderful smart objects that have been hacked together include Twettle: a wi-fi-enabled kettle that can send a tweet when it boils, a Twitter-enabled toilet to tell the world when it's flushed - yes, really - and a Twittering toaster. There is also this Twittering tree...

Ingenious hardware hackers such as the creators of Twettle, Twoilet and Twoaster won't be needed to create the IoT, however. It will be driven by cheap, ubiquitous wireless sensors piggybacking on ubiquitous wi-fi and cellular networks - the ones that are already all around us. Forget the expensive radio collars used by scientists to study wild animals. The IoT will be powered by wireless sensors that are cheap enough to slap on a Lion Bar, not just a lion.

How many smart objects are we talking about then? Millions? Billions?

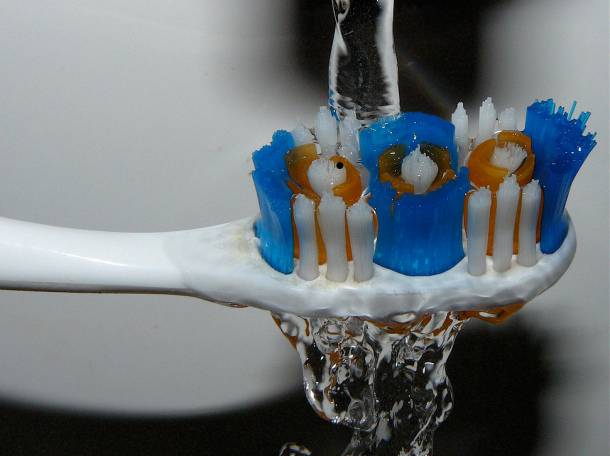

The sky's the limit really - how many objects are there in the world? Last year networking-kit maker Ericsson stuck its neck out to predict 50 billion connected devices will be plugged into our networks by 2020. "All devices will have connectivity - your cameras, your everything," said the company's VP of systems architecture, Håkan Djuphammar. "I'm not sure if you will have broadband in your toothbrush but maybe your dentist wants to know [how you brush your teeth] so why not? Connect everything."

What could your toothbrush say about you?

(Photo credit: cursedthing via Flickr under the following Creative Commons licence)

Also speaking last year, Intel's John Woodget, global director, telecoms sector, was a little more circumspect in his crystal-ball gazing - but he reckoned we should be banking on at least 20 billion connected devices by 2020.

OK but why would I want to get all that stuff online? What's the point of being able to pinpoint my toothbrush in cyberspace? I know where it is already: on the bathroom sink where I left it.

It all comes down to data - and, crucially, what can be done with that data once it's analysed, mined, visualised and so on.

From a consumer point of view, use cases for an IoT are many - from locating misplaced items and refilling your fridge, to monitoring your health. Enterprise uses are typically centred on creating more efficient business processes - ones that are smart and even self-regulating - thereby cutting costs and perhaps reducing risk.

For instance, chip factories already use sensor-based process optimisation because they are dealing with expensive components in a manufacturing environment where there is only a tiny margin for error.

Another example of an industry that is already utilising IoT...

...applications in tracking customer behaviour is insurance. If a motorist can be shown to use their vehicle infrequently they can be offered a lower premium than the driver who racks up hundreds of miles on a daily basis and tends to ignore the speed limit. Sensors in the vehicle wirelessly convey distance travelled, location and speed data and more back to the insurance company which then analyses this data to calculate a premium which is tailored to the specific driving abilities - and risk - of that particular motorist.

I'm not sure I'm comfortable with my insurance company knowing exactly where, when and how I drive...

You're not alone. Privacy concerns are a massive issue looming ahead for the internet of things. With so much real-time data potentially becoming available it's easy to fast-forward to an Orwellian dystopia where every one of our actions, transactions and interactions can be scrutinised for transgressions, analysed for money-making opportunities and/or data-mined for behavioural predications. Minority Report eat your heart out.

Last year the European Commission issued a set of guidelines for how RFID should be used - with the aim of reassuring the public that an evil cartel of corporates is not hell bent on the destruction of all human free will.

But in an IoT 'Action plan for Europe', also published last year, the Commission made rather less reassuring noises for privacy advocates: suggesting an internet of things is, by definition, likely to change society's understanding of privacy.

Could the internet of things help your insurance company know how you drive?

(Photo credit: Alan Vernon via Flickr under the following Creative Commons licence)

The EC noted in its report: "Social acceptance of IoT will be strongly intertwined with respect for privacy and the protection of personal data, two fundamental rights of the EU. On one hand, the protection of privacy and personal data will have an influence on how IoT is conceived. For example, a home equipped with a health monitoring system could process some of the inhabitants' sensitive data. A prerequisite for trust and acceptance of these systems is that appropriate data protection measures are put in place against possible misuse and other personal data-related risks.

"On the other hand, it is likely that the uptake of IoT will affect the way we understand privacy. Evidence for this is given by recent ICT evolutions, such as mobile phones and online social networks, particularly among younger generations."

Or in other words: the Facebook generation's propensity for publishing all manner of personal data online could be a sign that privacy 'as we currently know it' is already on the wane and society is driving towards another, altogether more 'on the record' future.

For those who would rather their data stayed safely hidden in the tin trunk under their bed that's doubtless a very scary prospect indeed.

Yikes! Anything else I should know before I get busy panicking about privacy?

Managing vast amounts of data - not just in the storing sense but in the analysing sense - is going to be big business. Think: data-mining, data visualisation and so on.

In the words of Michael Chui, senior fellow of the McKinsey Global Institute, who recently co-authored a report on IoT: "[The internet of things] will drive data storage requirements but perhaps more importantly it will drive data analysis requirements which is not only a technology question but also a talent question in making sure that you have people who can actually extract business value from the tremendous amount of data that will be generated.

"Analysis software will have to continue to evolve and deal with a huge amount of data... [And] the ability to visualise, or at least communicate this information to humans, will have to improve."

So if you have a head for figures, and an eye for graphs, charts and tables, your future career prospects might convince you to welcome tomorrow's sensor-driven world.