Clerk of the House of Commons: metadata can be more revealing than content

Sir Robert Rogers, the clerk and chief executive of the UK’s House of Commons, has given evidence that communications metadata and content are treated “fundamentally the same” when it comes to questions of Parliamentary privilege.

In written evidence (PDF) given to the Privileges Committee of the New Zealand House of Representatives, Rogers, a 40-year veteran of Parliament, said bulk metadata can be very revealing, in some situations more revealing, than the content of a communication.

Therefore they are treated in the same way by the House of Commons when it comes to releasing them to enquiries and law enforcement agencies.

“The selective mining and release of such metadata could constitute the processing of personal information of the kind that ought not to be released without a good and lawful reason,” he wrote in evidence titled “Use of Intrusive Powers within the Parliamentary Precincts”.

The evidence was given to inform an enquiry into why and how New Zealand MP Peter Dunne’s metadata was provided to another enquiry probing the leak of a report into the activities of New Zealand security agency GCSB.

GCSB had been found to be spying illegally on around 85 people, including Mega Upload founder Kim Dotcom.

The issue of whether gathering metadata constitutes surveillance of communications has been contentious ever since NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden began releasing documents he illicitly collected while contracting to the USA’s National Security Agency (NSA).

Snowden revealed massive programmes to collect such data run by both the NSA (called PRISM) and the UK’s GCHQ (dubbed Tempora) and shared with other partners in the “Five Eyes” community of English speaking nations, which also includes Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Supporters of the surveillance programmes on both sides of the Atlantic have repeatedly sought to justify them by drawing a distinction between the collection of metadata and of content.

In the US Senator Dianne Feinstein wrote that the NSA is not breaching the US Constitution’s Fourth Amendment, prohibiting unreasonable searches, because it does not collect the content communications and nor do the records include names or locations.

“The NSA only collects the type of information found on a telephone bill: phone numbers of calls placed and received, the time of the calls and duration. The Supreme Court has held this ‘metadata’ is not protected under the Fourth Amendment,” she wrote in USA Today last month.

Last month in the UK, former Conservative MP Louise Mensch called for the UK Government to crack down on The Guardian newspaper which has led with many of the Snowden leak stories.

Mensch argued the collection of metadata was a far cry from collecting the content of communications.

"Google does it to you every day. Frankly, everyone does it," she is reported as saying.

Like Rogers, Snowden has stressed how metadata can be more revealing than content.

"The metadata tells you what out of their data stream you actually want," he told Germany's Der Spiegel.

It can be used to go back in time and scrutinise every decision you’ve ever made, he has also said.

“Every friend you’ve ever discussed something with. And attack you on that basis, to derive suspicion from an innocent life, and paint anyone in the context of a wrongdoer.”

Snowden’s leaks indicate the UK’s Tempora programme goes further than the NSA’s in, among other things, storing not just metadata, but also content. Metadata was held for 30 days while the communications themselves were held for three days.

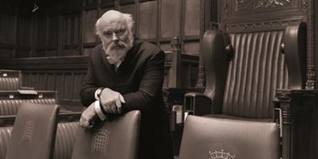

Below: Sir Robert addresses TEDxHousesofParliament.