Enterprise systems: "Time to stop the madness"

Despite frequent association with large-scale waste and failure, enterprise systems form a critical part of the global economic infrastructure.

The tension between waste and ubiquity creates a love-hate relationship among those who recognize the need for these systems and folks who consider them inefficient relics of a bygone era of computing.

A thought-provoking post by Tim Bray (respected Internet pioneer, entrepreneur, and one of the inventors of XML) discusses tensions inherent in large systems. Tim highlights important aspects of the problem and does a good job laying out the conundrum of large enterprise systems.

With Tim's permission, I'm reprinting his post on this subject, which is called Doing It Wrong. Tim takes a strong position on the need to address these issues:

I don’t know what my future is right now, but this seems by far the most important thing for my profession to be working on.

Please comment with your view of this issue, which I believe is of fundamental importance to the future of enterprise software.

- Related: Tim Bray's Enterprise 2.0 conundrum

------------

DOING IT WRONG

by Tim Bray

I work at Sun Microsystems. The opinions expressed here are my own, and neither Sun nor any other party necessarily agrees with them.Enterprise Systems, I mean. And not just a little bit, either. Orders of magnitude wrong. Billions and billions of dollars worth of wrong. Hang-our-heads-in-shame wrong. It’s time to stop the madness.

These last five years at Sun, I’ve been lucky: I live in the Open-Source and “Web 2.0” communities, and at the same time I’ve been given significant quality time with senior IT people among our Enterprise customers.

What I’m writing here is the single most important take-away from my Sun years, and it fits in a sentence: The community of developers whose work you see on the Web, who probably don’t know what ADO or UML or JPA even stand for, deploy better systems at less cost in less time at lower risk than we see in the Enterprise. This is true even when you factor in the greater flexibility and velocity of startups.

This is unacceptable. The Fortune 1,000 are bleeding money and missing huge opportunities to excel and compete. I’m not going to say that these are low-hanging fruit, because if it were easy to bridge this gap, it’d have been bridged. But the gap is so big, the rewards are so huge, that it’s time for some serious bridge-building investment. I don’t know what my future is right now, but this seems by far the most important thing for my profession to be working on.

The Web These Days · It’s like this: The time between having an idea and its public launch is measured in days not months, weeks not years. Same for each subsequent release cycle. Teams are small. Progress is iterative. No oceans are boiled, no monster requirements documents written.

And what do you get? Facebook. Google. Twitter. Ravelry. Basecamp. TripIt. GitHub. And on and on and on.

Obviously, the technology matters. This isn’t the place for details, but apparently the winning mix includes dynamic languages and Web frameworks and TDD and REST and Open Source and NoSQL at varying levels of relative importance.

More important is the culture: iterative development, continuous refactoring, ubiquitous unit testing, starting small, gathering user experience before it seems reasonable. All of which, to be fair, I suppose had its roots in last decade’s Extreme and Agile movements. I don’t hear a lot of talk these days from anyone claiming to “do Extreme” or “be Agile”. But then, in Web-land for damn sure I never hear any talk about large fixed-in-advance specifications, or doing the UML first, or development cycles longer than a single-digit number of weeks.

In The Enterprise · I’m not going to recite the statistics about the proportions of big projects that fail to work out, or flog moribund horses like the failed FBI system or Britain’s monumentally-troubled (to the tune of billions) NHS National Programme for IT. For one thing, the litany of disasters in the private sector is just as big in the aggregate and the batting average isn’t much better; it’s just that businesses can sweep the ashes under the carpet.

If you enjoy this sort of stuff, I recommend Michael Krigsman’s IT Project Failures column over at ZDNet. Also, Bruce Webster is very good. And for some more gloomy numbers, check out The CHAOS Report 2009 on IT Project Failure.

Amusingly, all the IT types who write about this agree that the problem is “excessive complexity”, whatever that means. Predictably, many of them follow the trail-of-tears story with a pitch for their own methodology, which they say will fix the problem. And even if we therefore suspect them of cranking up the gloom-&-doom knob a bit, the figures remain distressing.

So, what is to be done?

Plan A: Don’t Build Systems · The best thing, of course, is to simply not build your own systems. As many in our industry have pointed out, perhaps most eloquently Nicholas Carr, everything would be better if we could do IT the way we do electricity; hook up to the grid, let the IT utility run it all, and get billed per unit of usage.

This is where all the people now running around shouting “Cloud! Cloud! Cloud!” are trying to go. And it’s where Salesforce.com, for example, already is.

If you must run systems in-house, don’t engineer them, get ’em pre-cooked from Oracle or SAP or whoever. I can’t imagine any nonspecialist organization for whom it would make sense to build an HR or accounting application from scratch at this point in history.

Of course, we’re not in the Promised Land yet. I’m actually surprised that Salesforce isn’t a lot bigger than it is; a variety of things are holding back the migration to the utility model. Also, you hear tales of failed implementations at the SAP and Oracle app-levels too, especially CRM. And Oracle is well-known to be ferociously hard at work on a wholesale revision of the app stack with the Fusion Applications. But still, even if things aren’t perfect, nobody is predicting a return to hand-crafted Purchasing or Travel-Expense systems. Thank goodness.

But Sometimes You Have To · I don’t believe we’ll ever go to a pure-utility model for IT. Every world-class business has some sort of core competence, and there are good arguments that sometimes, you should implement your own systems around yours. My favorite example, of the ones I’ve seen over the past few years, is the NASDAQ trading system, which handles a ridiculous number of transactions in 6½ hours every trading day and pushes certain well-known technologies to places that I’d have flatly sworn were impossible if I hadn’t seen it.

Here’s a negative example: One of the world’s most ferocious competitive landscapes is telecoms, which these days means mobile telecoms. One way a telecom might like to compete would be to provide a better customer experience: billing, support, and so on. But to some degree they can’t, because many of them have outsourced much of that stuff to Amdocs.

Given all the colossal high-visibility failures like the ones I mentioned earlier, what responsible telecom executive would authorize going ahead with building an in-house alternative? But at some level that’s insane; if your business is customer service, how can you bypass an opportunity to compete by offering better customer service? The telecom networks around where I live seem to put most of their strategic investments into marketing, which is a bit sad.

Plan B: Do It Better · Here’s a thought experiment: Suppose you asked one of the blue-suit solution providers to quote you on building Ravelry or Twitter or Basecamp. What would the costs be like? And how much confidence would you have in a good result? Consider the same questions for a new mobile-network billing system.

The point is that that kind of thing simply cannot be built if you start with large formal specifications and fixed-price contracts and change-control procedures and so on. So if your enterprise wants the sort of outcomes we’re seeing on the Web (and a lot more should), you’re going to have to adopt some of the cultures and technologies that got them built.

It’s not going to be easy; Enterprise IT has spent decades growing a defensive culture based on the premise that you only get noticed when you screw up, so that must be avoided at all costs.

I’m not the only one thinking about how we can get Enterprise Systems unjammed and make them once again part of the solution, not part of the problem. It’s a good thing to be thinking about.

------------

[Thanks to Tim Bray for allowing me to reprint his post.

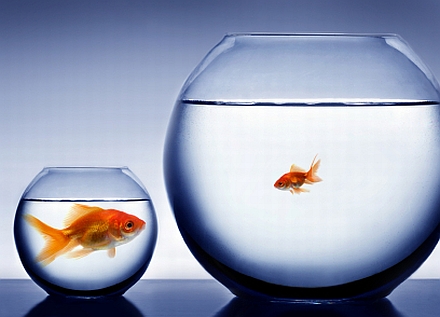

Fish photo showing that one size doesn't fit all is from iStockphoto. Caught in the middle of two evolutionary streams, the fish are probably confused and wondering, "What the hell is going on here?"

Photo of Tim from Alex Waterhouse-Hayward.]