Here's everything the FBI can demand from Yahoo without a court order

(Image: file photo)

Yahoo has become the first tech company to disclose three newly-unclassified national security letters, which the company received since 2013.

The web giant said Wednesday that it released the information following an FBI review, which determined that the customer data requested by the government should no longer be considered secret.

Security

The provision for reviewing secret demands for customer data from tech companies was included in the Freedom Act, which replaced parts of the controversial Patriot Act that were sunset in the wake of the Edward Snowden disclosures.

"We believe this is an important step toward enriching a more open and transparent discussion about the legal authorities law enforcement can leverage to access user data," said Chris Madsen, Yahoo's head of global law enforcement, security, and safety.

The national security letters, dated March and August 2013, and May 2015, were in part redacted to prevent disclosure of the FBI agents' names, Madsen said.

National security letters are subpoenas that are issued by the FBI in national security cases. They aren't authorized by a judge, and don't require any judicial review. They almost always come with gagging provisions, which prevent the recipient from disclosing to the customer -- or anyone else for that matter -- the contents of the order, or the very fact that they received one.

The government has argued that gag orders prevent tip-offs, which may result in leaks or destruction of data. But the provision was was found to be in breach of the First Amendment in a 2013 case. The government later appealed the ruling.

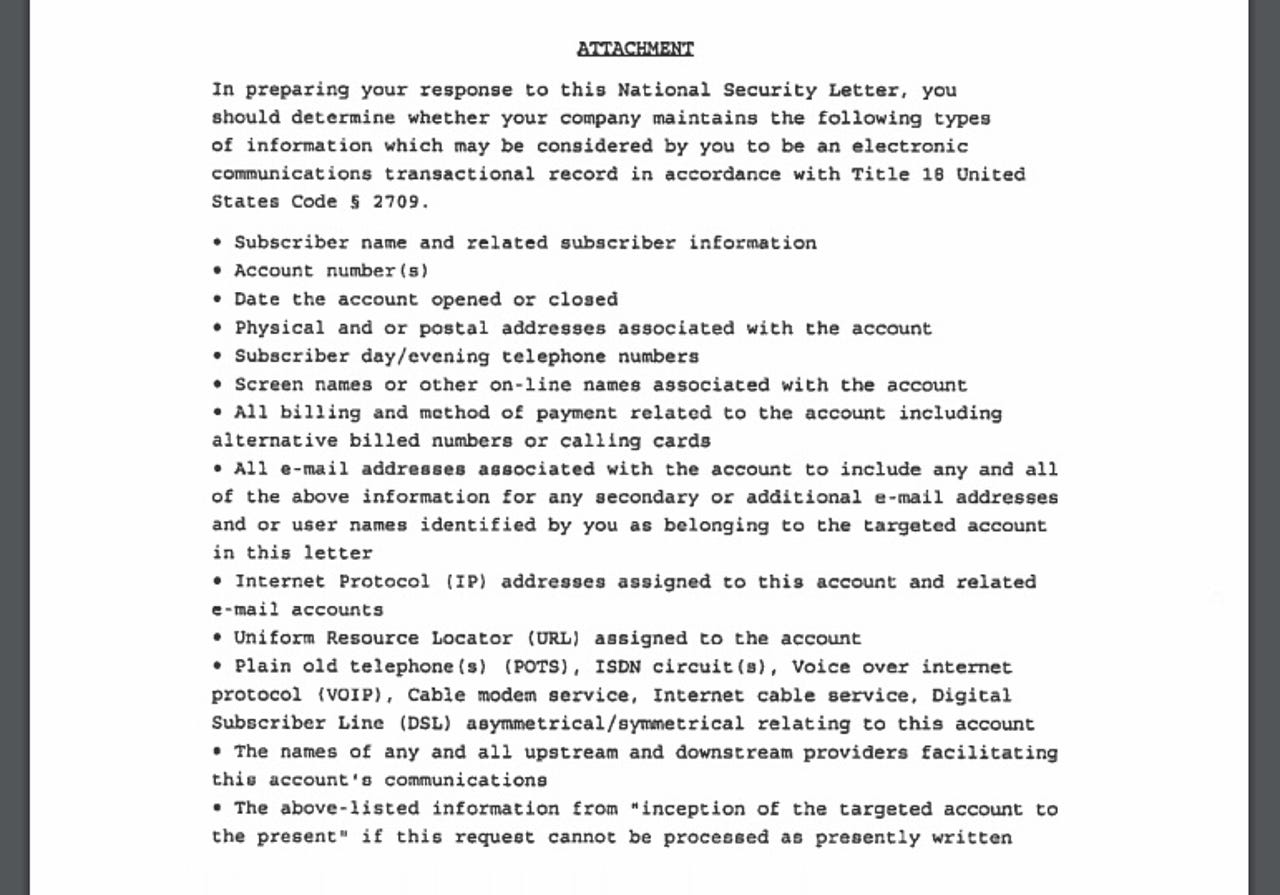

In Yahoo's case, this was the information that the company was compelled to turn over -- without a court order:

- Subscriber names and related information

- Account numbers

- Date the account opened or closed

- Postal address and phone numbers associated with the account

- Screen names and other online names associated with the account

- Credit cards and billing information associated with the account

- Any email addresses, including secondary or additional email addresses

- IP addresses assigned to the account and related email accounts

- URLs and other address-based data relating to the account

- Any hardware-related information relating to the account, such as ISDN or DSL data

- Names of any and all upstream and downstream providers facilitating the communications of the user

It's similar to but more expansive than the first national security letter that was ever disclosed earlier this year by Nicholas Merrill, founder of internet provider Calyx Internet Access, who won a decade-long case to release the letter.

Merrill's case revealed that the government can compel companies to turn over complete web browsing histories, the IP addresses of everyone a person has corresponded with, online purchase information, and also cell-site location information, and more.

While it was known that these FBI subpoenas can demand customer and user data, it wasn't known exactly what kind of data -- or how much.

Microsoft became the latest company to sue against the gag order provisions, arguing that they prohibit free speech and are therefore unconstitutional.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) later filed a motion in support of the software giant's case.