How Nasa astronauts use IT on the International Space Station

An astronaut's view on iPads in space, system outages and zero-G typing

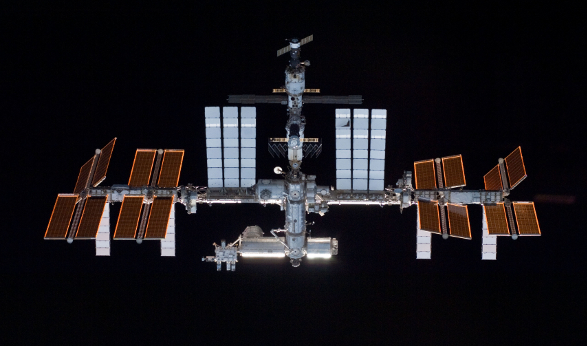

Clayton Anderson is an astronaut who logged 167 days in space, including five months on board the International Space Station in 2007. During silicon.com's recent visit to the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas he spoke to senior reporter Nick Heath about running and repairing the station's computers and why the iPad could be suited to life among the stars.As they circle the earth at 17,500 miles an hour, the crew of the International Space Station (ISS) depend on the smooth running of their onboard computer systems.

The ISS command and control computers are the heart of the station, controlling everything necessary to keep its crew alive - powering systems ranging from life support to communications.

The crew of the International Space Station rely on computers for their physical and psychological wellbeing

(Photo credit: Nasa)

The crew use laptops to access the command and control computers, using a GUI that allows them to navigate through schematics of the station's various systems - for example, heating or electrics.

According to Anderson, the central command systems interface is as easy to pick up as an off-the-shelf word processor, although the system requires extended training to master.

"It requires extensive training but the concept is like Microsoft Word. You can look at the software package and begin to use it relatively quickly," he said.

"All the displays are standardised and, as you begin to play with them, you know what buttons to push and how to operate the standard graphical interface."

Less critical to station safety, but almost as important to the astronauts, is...

...the separate network of laptop computers that the station carries, allowing the crew to make IP phone calls or email their family, as well as to watch movies or read digital books.

"It's very big psychologically to be able to speak to your family on the weekends, and read their emails and send them photos," Anderson said.

Using computing in zero gravity brings its unique challenges, with the crew having to anchor themselves down before they start using a laptop.

"We use foot loops that allow us to park our feet - if you put a finger on the computer and you don't have something to restrain you, you can float away," Anderson said.

Despite their use of seemingly modern tools like laptops and VoIP, station tech is always lagging several years behind that on the ground: a result of every piece of kit having to go through extensive safety and reliability testing.

A shot of GUI that station crew use to access the station's command and control computers

(Photo credit: Nick Heath/silicon.com)

Check out our photo tour of Nasa's Mission Control Center through the ages.

When Anderson was on the station in 2007, for example, the crew's laptops were only just being upgraded to IBM A31p ThinkPads, which first went on sale five years earlier.

"The computer you have today may be far better technically than what we have because of the certification that is needed to make sure the machine is solid enough, to make sure that the battery is safe and that everything will function properly in zero-G," Anderson said.

"It does mean [using the machines] is a lesser experience - the computer has to grind away for a little while before the data is available."

Email and internet also run at a slower pace than on the earth below, with the station email system updating itself on average three times a day and web browsing available only at dial-up speeds.

Viruses and system outagesGiven the fact that the ISS command and control computer systems control everything from life support to electrics - keeping any malicious software out of the system is a priority for Nasa.

"One of the biggest worries that we have with our computer system on board is malicious software and virus attacks," Anderson said.

Fortunately there are several...

...barriers to the ISS command and control computers getting infected - the only way that software code can sent to the control computers is through Mission Control and malware would also need to be written specifically to infect the ISS control computers, given the proprietary nature of the software they use.

Nasa teams on the ground also follow strict procedures before uploading any new software to the ISS core systems, carefully scoping any upgrades before testing them in a replica of the station's computer systems at Johnson Space Center, the home of mission control, in Houston, Texas.

"The software is upgraded periodically as we learn better ways to operate, or where we have problems, but all of that is a very controlled process," Anderson said.

In spite of the rigorous testing procedure that every piece of hardware and software is put through before it is deployed, inevitably there is still the occasional hiccup with the computers on board.

Within days of Anderson boarding the station, all six of the computers controlling life support and other vital functions on the Russian side of the station went down following a power surge, requiring emergency repair work to be undertaken by the Russian crew.

Astronaut Clayton Anderson spent five months on board the International Space Station in 2007

(Photo credit: Nasa)

If a fault does occur in the command and control computer systems, much of the time it can be dealt with by a combination of automated software and operators within Mission Control.

"The system is smart enough to know when a failure occurs. When that failure occurs there is automated software that attempts to put you in a situation where everything is stable and safe," Anderson said.

However, sometimes problems will occur that will require the crew to access the station's command and control computer, diagnose the fault and manually shut down parts of onboard systems.

"There are some major failures where the...

...crew is definitely required," he said.

"We have something called an unknown bus loss failure - if an electrical power bus fails it manifests itself with the lights going out in the laboratory module. It's almost like a power outage on the ground.

"If we have a certain configuration of lights going out the crew has to decipher what has happened and go to the procedures and begin to evaluate and send commands to help begin to recover that system."

As well helping the station recover from technical outages, the crew is also called upon to carry out upgrades to the station's IT infrastructure from time-to-time.

During Anderson's time on board he installed a local area network throughout the station, requiring him to run ethernet cable throughout the station's cramped and crowded interior.

"It was quite difficult - there were I don't know how many wires coming out of the central panel and they all had to be bundled up and routed through the rest of the station.

"I was given guidance from the ground and they said the wires need to go under here, over here, around here, through here."

Anderson also upgraded software on the station, either by swapping out old hard drives or updating systems using a CDs or DVDs.

And while station tech upgrades happen a slow and deliberate pace, it seems that eventually even the iPad may find its way on board the station.

"All groups - the US, the Europeans, the Russians, the Japanese - are always constantly evaluating new technology and how it might benefit us.

"Portability, ease of use and battery power is critical. We have toyed with the old PDAs and looked at tablet PCs, obviously with the popularity of something like an iPad, that's very possible," Anderson said.

Discover more space tech in our gallery showing off some of the US' earliest satellites.