How this antique technology could turn out to be the future of broadband

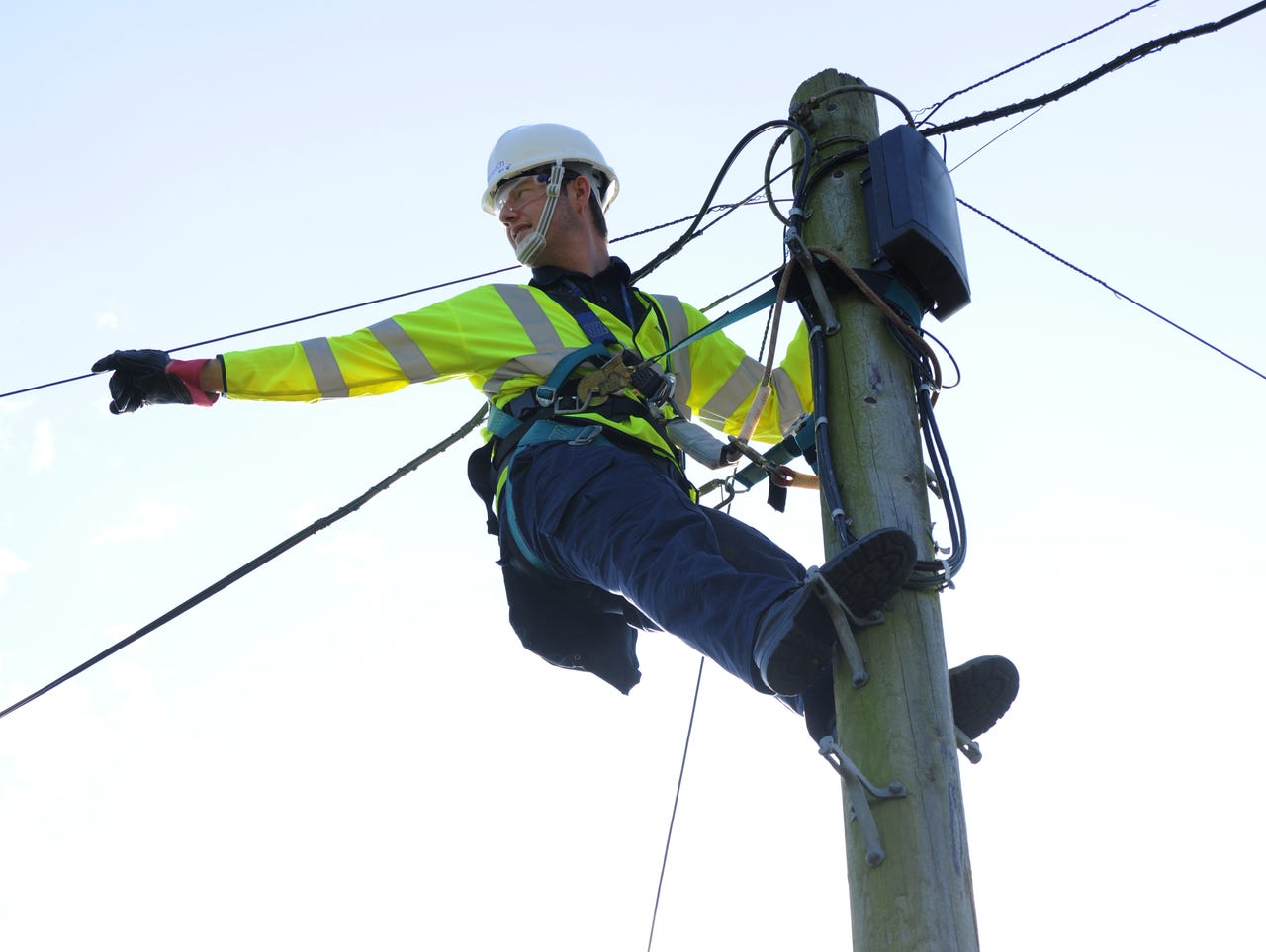

G.fast distribution points can include telephone poles and manholes.

If you're still waiting for your ISP to announce when it will bring fibre to your premises and you suspect 'sometime the otherside of never' is the answer, take heart. You may already have the line needed to deliver 1Gbps to your home or office already in place.

Copper networks went into the ground in some countries over 100 years ago, and were more recently the first networks used to deliver broadband to customers. However, copper was also viewed as a technology dead end: only capable of offering tens of megabits per second, it was just a staging post until fibre to the premises (FTTP) replacements could be installed, bringing broadband speeds into the hundreds of megabits per second and beyond.

That was, of course, until G.fast came along.

G.fast is a new-minted standard being explored by operators in Europe, Australia, Asia, and beyond, as a means of offering fibre-like speeds over those creaking copper wires.

Using the existing copper infrastructure, G.fast can offer a 1Gbps downlink over 20m copper loop, and several hundreds megabits per second over hundreds of metres.

As with most communications technologies, there's a reach versus rate trade-off -- the further the signal has to travel, the lower the speed you'll get -- but those distances are long enough to bring ultrafast broadband to premises years earlier than with FTTP.

Even with the reach versus rate trade-off, the technology can be used not only between distribution points (broadband networking boxes often found on lampposts or down manholes) and the premises they connect 30m to 40m away, but also from homes to street cabinets, that tend to be a little bit further away at 300m to 400m. Without G.fast, premises at an equivalent distance to a fibre-connected cabinet would be looking at top speeds in the region of around 70Mbps to 80Mbps in a best-case scenario.

G.fast can offer speeds so much faster than other copper technologies by making use of a far greater range of spectrum. "The [G.fast] standard allows the use of frequencies from 2Mhz all the way up to 106Mhz, so you've got that massive multiplier in terms of the amount of spectrum you can use on each line. That's where those great headline speeds come from. The ability to do that 1Gbps is because you're using 100Mhz of spectrum on that line," Trevor Linney, head of access network research at BT, told ZDNet.

"The performance we've seen in the field trials is in line with the measurements we've seen at the labs, and it's helped build confidence that what we're predicting from the equipment will be realised. It's performing well," he added.

G.fast holds a lot of promise, but remains in its infancy, having only been standardised in 2014. While many ISPs are conducting trials of the tech or otherwise exploring it, few are ready to roll it out as a commercial product. Nokia, for example, has seen over 30 of its ISP customers begin pilots, and four begin deploying G.fast in its networks. Japanese broadband provider Energia will begin offering the service in the Chugokua region of the country from the middle of this year.

Elsewhere, Switzerland's Swisscom plans to begin its commercial rollout from the end of 2016. Others experimenting with the technology include Orange's Polish arm, Germany's Deutsche Telekom, and Telekom Austria's subsidiary A1.

While a technology like G.fast that works over very short distances won't solve the perennial problem of rural broadband, it can give ISPs a way of hiking speeds significantly without as much cost, hassle, and time as a full FTTP rollout would require. FTTP requires getting access to buildings, making appointments with tenants and owners, and sending engineers into people's home and offices; G.fast doesn't.

"Five years ago, the answer was simple: you had to do fibre to the home. And then people realised, yes, it's the best technology and we're going to go there, but it's going to take 20 years because you need to go to every village, every street, every building, and it's going to cost a lot of money... [G.fast] is going to allow you to deploy very quickly compared to bringing fibre into every building," Stefaan Vanhastel, a director at Nokia's fixed line division, said.

According to BT, which is currently trialling G.fast in two areas of England and one in Wales, a G.fast deployment across the UK would be five times cheaper than an equivalent FTTP one, and would be five times quicker. If all goes well, BT expects to pass 10 million premises with G.fast by the end of 2020, and the majority of UK premises within the next decade.

Given that G.fast allows operators to squeeze more from their existing copper infrastructure rather than swapping it out for FTTP, there have been fears that the technology will give ISPs an excuse to delay those hoped-for fibre upgrades, leaving customers waiting longer for the highest speeds.

It's a charge the industry unsurprisingly refutes. "The interest [in G.fast] comes from many service providers. We see it from operators continuing to upgrade their copper plans. They went from ADSL to VDSL, and now they're going to G.fast, all the while building out a fibre network that gets very close to the end user and will ultimately reach the end user," Nokia's Vanhastel said.

"I'm not convinced that if you deliver an ultrafast service into people's homes, and they see the 300Mbps, and when they go to use it's there, I'm not sure they're that worried about whether the piece of glass stopped in their lounge or whether it was further back in the network," BT's Linney added.

Ovum analyst Matthew Howett agrees that the technology itself may not be at the forefront of customers' minds when thinking about G.fast.

"The challenge that companies like BT and others have got is communicating [G.fast] to the end user, because a lot of people don't really care what the technology is, they just want the speeds. If you approached someone on the street and asked people what G.fast was, they would probably think it was some sort of indigestion medication.

"BT has got a challenge to communicate [what G.fast is] to customers and I think that's best done with the sort of things you can do using it. I'd be surprised if you can find many customers that wouldn't be happy with 150Mbps, that serves most consumers' needs today. BT has got to realise that they don't care if it's called G.fast or anything else, they just want to think about it in terms of what they can do with those speeds," he said.

Branding worries don't seem to be affecting ISPs when it comes to G.fast, and telcos are already working on the technology's successor, XG-FAST. Deutsche Telekom recently announced that it had managed to get 11Gbps out of two bonded copper pairs over 50m in its labs, while a similar BT trial managed 5Gbps over 35m.