Intel slows the rate of major chip upgrades as Moore's Law falters

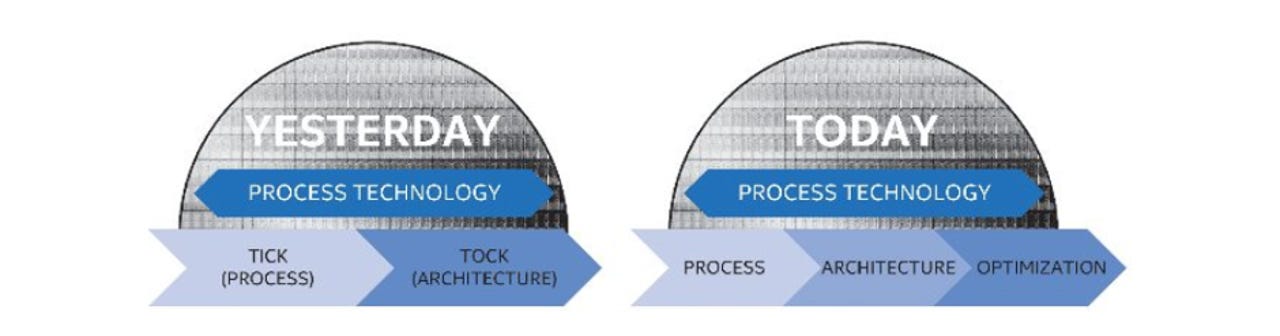

A comparison of Intel's old and new approaches to chip manufacturing.

For decades the processing power of computers grew steadily, thanks to the number of transistors being packed onto chips doubling roughly every two years.

The trend, known as Moore's Law, has been wavering for some time and suffered another blow yesterday after processor giant Intel announced a fundamental change to how it makes computer chips.

Intel is to abandon the 'tick-tock' approach to manufacturing chips it has used for several years, in a move seemingly prompted by the increasing difficulty of continuing to shrink transistors and circuits on a chip's surface.

The 'tick-tock' model described the approach Intel took to making new chips. Roughly every other year Intel would upgrade its fabs to manufacture chips using smaller transistors and circuits, which in turn increased transistor density and therefore the performance and energy efficiency of these processors. This was known as a 'tick'.

In the year between these ticks Intel would release chips with a new microarchitecture -- this was known as a 'tock'.

In practice, this resulted in a cycle where Intel released a chip based on a new microarchitecture one year, followed by a new chip based on the same microarchitecture but manufactured using smaller and more densely-packed transistors.

This approach will change, as Intel has announced it will slow the rate at which it shrinks transistors for its chips.

Rather than using the 'tick-tock' manufacturing approach, Intel will move to what it calls 'process, architecture, optimization'.

Intel has already informally adopted this approach with its current crop of processors based on a 14nm manufacturing process. The size 14nm relates to how closely transistors are packed together on the chip's surface. As Intel shrinks chip transistors, so this nm figure reduces in size.

Intel had planned to release two 14nm chips -- Broadwell and Skylake -- and then release a 10nm chip in 2016 called Cannonlake. However, last year it announced it was delaying the release of the 10nm Cannonlake until 2017 and would instead release another 14nm chip in late 2016, known as Kaby Lake.

Rather than being a shrink of Skylake or being based on a new microarchitecture, Kaby Lake is based on the same microarchitecture as Skylake but with performance enhancements and new features compared to its predecessor.

Intel has indicated it will continue to follow this more drawn-out approach when releasing chips, at least for the near future, stipulating it will take a similar tack when releasing processors based on a 10nm manufacturing process.

"We expect to lengthen the amount of time we will utilize our 14nm and our next-generation 10nm process technologies, further optimizing our products and process technologies while meeting the yearly market cadence for product introductions," the company says in its 10-K filing.

It remains to be seen how attractive new Intel chips will be to consumers and businesses without the improvements that come from moving to a smaller manufacturing process or a new microarchitecture. How well Kaby Lake sells will likely depend on how significant the promised performance enhancements over Skylake are.

The reasoning behind the manufacturing slowdown isn't identified in the filings but Intel CEO Brian Krzanich has previously discussed the difficulty of manufacturing chips at 10nm and below.

"The lithography is continuing to get more difficult as you try and scale, and the number of multi-pattern steps you have to do is increasing," he said in a conference call last year.

Chips manufactured at 10nm and below have a tendency to suffer from current leakage due to limitations of traditional photolithographic methods. While a manufacturing process called 'extreme ultraviolet lithography' is being explored by Intel, Samsung, and TSMC as a way of manufacturing chips at this size, it is not yet being used in production.

Intel doesn't anticipate this manufacturing slowdown will see it fall behind competitors, given the lead it currently enjoys in its manufacturing process.

"We have a market lead in transitioning to the next-generation process technology and bringing products to market using such technology," it says in its filing.

Chipmaker TSMC is not expected to start making chips in significant numbers using a 7nm manufacturing process until 2017.

One advantage to consumers and businesses of this manufacturing change could be that machines are easier to upgrade, thanks to new Intel CPUs not requiring a new motherboard socket as frequently as in the past.