ISPs versus SOPA: Anti-piracy bill could force severe privacy-invading measures

Internet service providers in recent weeks have spoken out publicly against the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), which threatens the very free and open nature of the web as we know it.

With the daunting realisation that the Act may actually go through, web providers are desperately adding their voice to the collective of civil rights campaigners, Internet privacy rights groups and major web-based giants from social networks to search engines.

But it is not in a bid to forego the moral objection that the rest of the U.S. will feel once the law does all but inevitably pass through. Instead, it falls down to cost and infrastructure, and the corporate resistance to change.

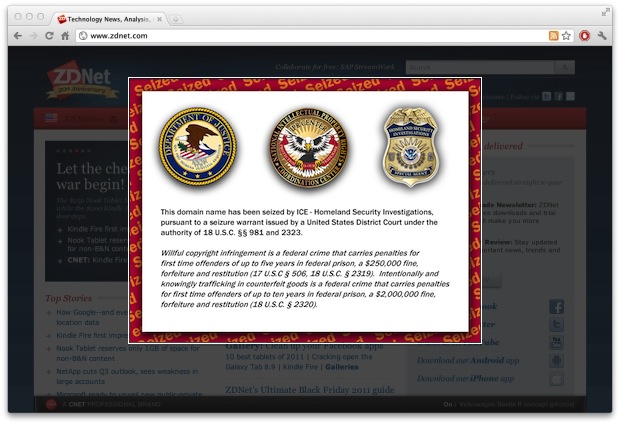

SOPA could force web providers to "prevent access by its subscribers located within the United States", which will block access to alleged copyright infringing websites.

But as sister site CNET reports, the wording has somewhat changed from the earlier Senate bill, known as the Protect IP Act, that now suggests AT&T, Verizon, Comcast and other web providers could block their customers from accessing certain sites.

The U.S. Chamber of Commerce supports the anti-piracy bill, including the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA) and the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), who represent some of the largest names in the U.S. film and music industries.

This could not only include the blocking of a website in its entirety, through existing processes for domain name seizures, but the Act could force net service providers to block IP addresses also.

As warned by Markham Erickson, head of NetCoalition, which counts Amazon, Google and Yahoo, amongst many others as part of its anti-SOPA efforts, these measures could also include the controversial deep packet inspection.

In a guest column for CNET, Cary Sherman, the RIAA's chief, suggested that SOPA could not be as wide-ranging as people thought, asking Americans to "take a deep breath":

"Cutting off funding or access to only the illegal part of the site while leaving the rest of the site intact promotes legitimate expression."

But while domain name seizing from a top-level-down perspective will block the vast majority from accessing the website, IP blocking will mean the affected user will not be able to bypass the domain name block by entering in the website's IP address.

Deep packet inspection (DPI), however, is a technology designed to monitor each and every bit and byte sent across a network, and has been heavily criticised as a targeted, privacy-invading approach to anti-piracy.

DPI would instantly inspectpackets of data sent and received by the customer to determine whether the content is infringing copyright. It would be deep-level wiretapping, that would enable web providers to collect every shred of data the customer sends and receives, which could then be filtered or blocked if the content was deemed unlawful.

The data could, in line with data retention policies, be used against the customer if wide-ranging court orders were granted to seek access to that data. Seeing as cell networks in some cases hold your browsing data for years, imagine the content that could be used against you over a similar period of your home broadband account?

Some smaller ISPs are particularly critical of SOPA, as it would result in the complete re-engineering and re-deployment of their networks, which could result in the closure of many smaller web providers.

The change in language from the Senate to the House version sheds light on why so many Internet companies and web service providers are so opposed to the bill. Not only would it infringe the web on a civil and social level, the blocks that would need to be put in place would have to be paid for by the web providers themselves. And, as often as is the case, it will be the customer having to pay for the 'privilege' of having restricted web service.

SOPA is designed to counter the rise of 'rogue' piracy infringing websites, often based outside the United States but use U.S. controlled domain names, such as .com, .org and .net top-level domains. It will allow the U.S. government to censor U.S. web users from accessing websites based on copyright claims, which could be rogue applications in their own nature.

This could lead to widespread blocking of popular websites -- many of which oppose the bill, including Facebook, Google and photo-sharing site Flickr -- as well as a rise in abuse of the system from competitors or those out to make a quick buck.

One of the key problems with SOPA is that the bill, currently going through the U.S. House of Representatives, is laden with vague and seemingly wide-ranging language and can -- and probably will -- be misinterpreted by the judiciary of whom will have the final say of whether a website is blocked. This is currently the case in the UK for example, where websites can be blocked under the equally vague Digital Economy Act under a non-juried court order.

Having said that, the non-specific language used in the bill could allow a certain level of allowance for smaller ISPs, which either do not have the funding or the resources to carry out deep packet inspection on its networks, to attempt other blocking mechanisms instead:

Section 102 (c.2.A.i) says that service providers shall:

- "...take technically feasible and reasonable measures designed to prevent access by its subscribers located within the United States to the foreign infringing site (or portion thereof) that is subject to the order, including measures designed to prevent the domain name of the foreign infringing site (or portion thereof) from resolving to that domain name's Internet Protocol address. Such actions shall be taken as expeditiously as possible, but in any case within 5 days after being served with a copy of the order, or within such time as the court may order.

The RIAA argues that SOPA is a "flexible" bill, and even more so than the more-specific Senate bill.

But as it could trigger the mass exodus from larger web providers to the smaller, lesser-known suppliers that only carry out domain blocks or IP blocks, it would no doubt result in larger web providers in asking for a 'one size fits all' approach, which in itself would be seen as an anti-competitive move.

Nobody can win, in effect.

But it does make one wonder. Whether or not a website has had its commonly-used domain name seized, or whether the website's servers have had its IP address blocked, or whether deep packet inspection on a minute level blocks access to a site, it makes little to no difference.

For the vast majority, as most web users will not have the technical skill to bypass the blocks in place, SOPA will turn the United States -- seemingly the land of the free -- despite what one Democrat says, into a state of online oppression that would rival the controlled nature of the web in many Middle Eastern countries.

Related:

- Between the Lines: SOPA: Why the 'broken web' should stay broken

- SOPA, pols run into Internet buzz saw

- Cell networks hold customer data 'for years' for law enforcement use

- London Calling: European Parliament ‘opposes’ SOPA copyright law in new resolution

- What we missed this week: SOPA, Net neutrality, UK online outlaws, Google’s effect on spying

- iGeneration: UK anti-piracy laws passed: 'Fears of wave of censorship' raised

Around the network:

- CNET: SOPA's latest threat: IP blocking, privacy-busting packet inspection

- OpenDNS: SOPA will be 'extremely disruptive' to the Internet

- SOPA bill won't make U.S. a 'repressive regime,' Democrat says

- CBS News: SOPA opposition from tech heavyweights Google, Facebook

- Backers defend controversial online copyright bill