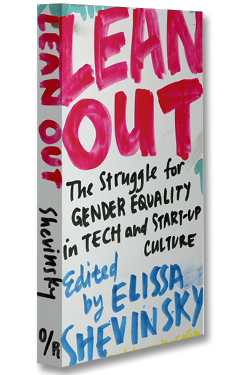

Lean Out, book review: Still waiting for change

These guys were a tiny minority and they had no control over my career. Now imagine that you're in a business where almost everyone around you is like that and they're your co-workers, managers, bosses, and they can control your life. That is the experience recounted by the many authors of Lean Out: The Struggle for Gender Equality in Tech and Start-Up Culture. They work -- or, sometimes, worked -- in start-ups and major companies, in venture capital firms and research labs, mostly in Silicon Valley.

But first, some numbers. According to Eliza Swallow, 4.2 percent of partner-level decision-makers in venture capital firms are women, compared to 4.6 percent of Fortune 500 CEOs. Men are 60 to 70 percent more likely to get funding -- and attractive men are 36 percent more likely to get funding than everyone else. Women win only 7 percent of venture capital funding, and founded 11 percent of the US's high-growth ventures. When Swallow interned at a venture capital firm, she suggested this was an opportunity. Her boss told her not to pursue the idea because after her internship ended there wouldn't be anyone -- that is, no-one female -- to follow it up. Men who like making money can't see female entrepreneurs as an under-served market? Is that sexism or laziness?

The culture described in these women's stories is certainly sexist -- and toxic -- enough. Dom Deguzman's straight male "brogrammers" expect their lesbian colleagues to ogle and catcall women the way they do. Pre-transition, trans woman Krys Freeman learned to be "fully complicit" in misogynistic, homophobic, transphobic behaviour to avoid becoming the butt of the "jokes". "Genderqueer" Squinky, whose first successful game was written while in high school, finds belonging in the games industry harder than making games. Erica Joy, the sole black female software engineer on a team of all-white males avoided complaining to human resources about a harassing co-worker because "I didn't want to be that stereotype, the black woman with a chip on her shoulder; I didn't want to make the rest of my team uncomfortable".

Dilemma

This all creates a dilemma for several of the writers: is it really right to encourage more of their fellows to join a field that is going to make them miserable? Ash Huang argues that sometimes leaving -- as many women are -- is the right option: "There are a thousand ways to carry a revolution." Not everyone can "lean in", as Sheryl Sandberg pushes them to do.

In her own essay and her commentaries on the others, editor Elissa Shevinsky writes, "It's wrong to ask women to come in and be the fix -- because women are not the problem." If a culture is toxic, the people it kills can't fix it. Change has to come from both genders working together. Teaching girls to code isn't enough, she says: blaming the pipeline is convenient for large companies like Google, whose efforts at diversity have included calling her for interviews on four separate occasions and never hiring her. Qualified women keep applying for jobs in tech companies, to speak at developers' conferences, for funding and internships -- and keep getting turned down by companies who insist they can't find women to hire. She cites Alihya Rahman's tweet from the Lesbians Who Tech conference: "I believe the best way to hire women and people of colors is to hire them."

What makes this book especially sad is comparing it to the 1996 book Wired Women: Gender and New Realities in Cyberspace, edited by Elizabeth Reba Weise, who covers biotech, technology, and food safety for USA Today, and Lynn Cherny, now a data analysis consultant. That book also included stories of industry sexism -- most notably by Paulina Borsook. But there was so much hope and excitement, too. Change, it seemed then, was just a matter of time and numbers.