Lifelike artificial lung does away with pure oxygen

Large mechanical ventilators in which blood from the patient is circulated through a machine to oxygenate it could one day be a thing of the past.

Researchers in Cleveland, Ohio, have built an artificial lung that reaches functional parity with a human lung. The device uses oxygen sourced from the air rather than pure oxygen as current man-made lungs require.

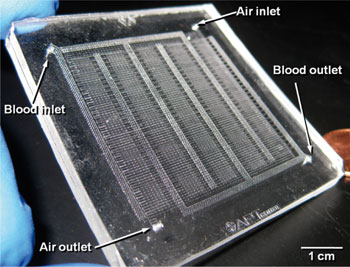

Potkay and his team fashioned microfluidic channels from an organic silicon polymer (PDMS) and created ever smaller channels until the rubber tubes measured less than one-fourth the diameter of human hair, similar to the arteries and capillaries in a real lung. They added blood and air flow outlets and inlets and coated all the channels in a gas exchange membrane.

By following the design of the natural lung and making the parts on the same scale, the researchers were able to create a very large surface-area-to-volume ratio and shrink the distances for gas diffusion compared to the current state of the art.

Tests using pig blood show oxygen exchange efficiency is three to five times better, which enables them to use plain air instead of pure oxygen as the ventilating gas. Current artificial lung systems require heavy tanks and can only be used on patients at rest due to their inefficient oxygen exchange.

"Based on current device performance, we estimate that a unit that could be used in humans would be about 6 inches by 6 inches by 4 inches tall, or about the volume of the human lung. In addition, the device could be driven by the heart and would not require a mechanical pump," Potkay said.

Not envisioned as a permanent transplant, the device would buy patients time while their own diseased lungs healed, or could act as a bridge while awaiting a lung transplant –- a wait that lasts, on average, more than a year.

Next for the team is to develop a coating to prevent clogging in the narrow artificial capillaries, and eventually, create a durable artificial lung large enough to test in rodent models of lung disease.

Within a decade, Potkay and his co-workers expects to have human-scale artificial lungs in use in clinical trials.

Potkay is the lead author of the paper describing the device and research, in the journal "Lab on a Chip."