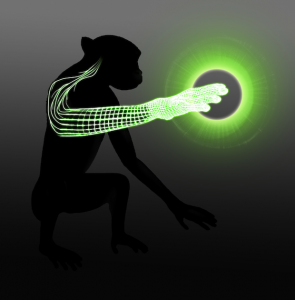

Monkeys move and feel virtual objects with their minds

This means monkeys can control objects on a computer display with a virtual arm controlled by their brain... while having the ability to 'feel' the textures of the objects on the screen.

The technique could lead to virtual prosthetic limbs and robotic bodysuits for amputees and patients with locked-in syndrome.

It's designed by Duke's Miguel Nicolelis and colleagues with the help of 2 rhesus monkeys named Mango and Tangerine.

- First, the monkeys used their real hands to operate a joystick to move a virtual image of an arm on a computer screen.

- Then team implanted 2 sets of electrodes into 2 parts of their brains: the motor cortex and somatosensory cortex. The motor cortex is involved in performing voluntary movement; the somatosensory cortex processes input received from cells in the body that are sensitive to touch.

- The monkeys were trained to use only their brain to explore objects on a computer screen by moving the virtual arms.

- Electrodes in the motor cortex record the monkeys' intentions to move, and then relay that info to the computer.

- As the virtual monkey hand sweeps over discs on the screen, electrical signals are fed into their somatosensory cortex through the second set of electrodes - providing tactile feedback of electrical pulses.

The monkeys were tasked to choose between visually identical objects; the only differences were in texture and treats (or lack of treats). Low frequency of pulses indicated a rough texture, high frequency indicated a fine texture.

They accurately distinguished between an object that produced an award (juice) - which was associated with an electrical stimulation when 'touched' - and objects that produced no electrical stimulation or treats, Nature News explains.

Nicolelis says that the combination of seeing an appendage that they control and feeling a physical touch tricks them into thinking that the virtual appendage is their own within minutes.

So really, its bidirectionality closes a loop, making this a brain-machine-brain interface, as well as a key component to future neuroprostheses.

Previous brain-machine interfaces have relied on visual feedback. But if you want to reach and grasp a glass, visual feedback won't help you. It's the sensory feedback that tells you if you have a good grip or if you are about to drop it.

Nicolelis's ultimate goal, and that of the Walk Again Project, is to build an exoskeleton suit to restore mobility to severely paralyzed patients. They would not only be able to walk and move their arms and hands, says Nicolelis, but also to feel the texture of objects they hold or touch, and sense the terrain they walk on.

Nicolelis hopes that a suit will be demonstrated at the 2014 World Cup in his homeland, Brazil, with the opening kick of the ball being delivered by a young Brazilian with quadriplegia.

The work was published in Nature yesterday. Via Nature News, ScienceNOW.

Images: Katie Zhuang / Duke

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com