New file super-compression: not snake-oil?

Snake oil and deception are usually the first things that spring to mind when a company touts a new method of making files many times smaller that anyone else has ever managed. I've lost track over my years as an industry reporter of the number of companies that have promised massive compression ratios but who disappeared or failed to deliver. You can't break the laws of physics, Jim.

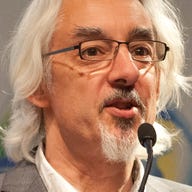

But yesterday I had a very interesting conversation with Chris Schmid, the COO of Balesio, a tiny Swiss company with just nine employees that's been selling super-compression technology into the rest of Europe for a little while now, and is planning to move into the UK market.

Balesio reckons that its technology can compress files up to 96 percent. Yes, that's what I said. But you know what? I believe that this stuff could work.

The secret sauce works on Microsoft Office and most image files right now, but the company will be adding one other well-known file format to its armoury soon which I'm under oath not to reveal yet.

The technology, which isn't actually compression in the strictest sense, examines the files' internals and 'optimises' them. Schmid explained that this consists essentially of three processes. The first is to look for so-called dead objects. These are leftovers from delete operations within the file that occupy file space that isn't recovered by the executable. It's just like disk defragmentation, so it removes the dead object and re-saves the now-smaller file, preserving its attributes.

The second process is to look at image files -- JPG, GIF, PNG and the like -- and examine how many colours they are actually displaying. Schmid told me that each pixel carries the bits for the maximum colour depth available for the file type but most files don't use all available colours. What Balesio's technology does is remove unused colour information on a per-pixel basis and re-save the file. This of course makes the file smaller, but does not change how the image looks in any way. Schmid reckoned that the files remain entirely within standards and can still be opened by the same applications as before.

This form of image compression can be performed not just on stand-alone image files but also on images within other files. Schmid reckoned that the biggest savings to be had from both image processing and dead object removal are in PowerPoint files. These often contain deleted images using up huge amounts of file space that hasn't been recovered, which accounts for the bloat you often see in these files. It works on image attachments in Outlook too.

The third process? This looks into Office files and converts any bitmap and TIFF images that are inside the file into a high-quality JPG, which might be 25 percent of the original's size. Schmid argues that including a BMP or TIFF image makes no sense in a PowerPoint presentation as there's no visual difference, but users often just drop them in anyway without considering their impact on file size.

As you might imagine, this level of bit manipulation is very CPU-intensive so the first run on a server full of data can take weeks to complete, said Schmid, much like the first backup takes much longer than successive incremental backups.

Balesio sells a desktop version, but the server version is the one that storage managers will want. Imagine running it on a storage system containing terabytes of end-user files, many of which are huge PowerPoint and Outlook files bloated by multiple copies of huge images. Deduplication can remove the repetition, but not make images smaller.

Does it actually work? I don't know but Balesio claims big names on its client list already, and I hope to try it out. But it looks like this could be one of those very rare beasts: a technology that reduces storage needs by going beyond what can be achieved using classic compression and deduplication technologies. All the same, I'd also do a trial run first, before unleashing it on millions of users' files...