Should Whitehall make iPhone apps? Yes, minister

Small can be beautiful when it comes to public sector IT...

Made-in-Whitehall iPhone apps are a sign the government is switched on to important developments in technology, says silicon.com's Natasha Lomas.

It's no secret the government has been responsible for more than its fair share of troubled IT projects - take the delayed and largely unpopular National Programme for IT for example, or the similarly underwhelming Defence Information Infrastructure project.

These aren't exceptions to the rule either - government IT history is littered with IT projects gone awry. When it comes to designing and deploying big software systems, the public sector's record is patchy to say the least.

But take a closer look at government IT and there's something exciting happening: Whitehall has dipped its toe into the world of smartphone apps.

Unless you've already downloaded one, you may not have noticed the quiet revolution going on. Why? Because these bite-sized IT projects have not been beset by budget overruns, delivery delays, performance issues and other familiar gremlins. They've simply been created and sent out into the mobile ether with little fanfare and minimal fuss.

How refreshing.

While it's perhaps too much to hope that the government's work on apps is the start of some sort of IT turnaround, it makes a good counterpoint to the whipping boy status that public sector technology has so often attracted.

But what about the apps themselves? What sort of mobile applications has the government been working on?

There's a Jobcentre Plus app which enables iPhone and Android smartphone owners to gain access to vacancies on the Jobcentre database and a Highways Agency app that offers real-time traffic updates for major roads to help motorists avoid getting stuck in jams.

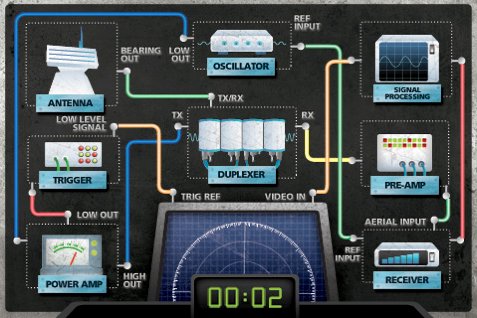

Then there's a Royal Navy iPhone app that allows would-be engineers to take part in training games - acting as a recruiting tool in the process. (Subtext: 'Join the Navy! It's fun!')

The Royal Navy's Engineer Officer Challenge iPhone app

(Image credit: Royal Navy)

And there's also the Department of Health which put out a Drinks Tracker app before Christmas, designed to help festive revellers calculate how many units of alcohol they've drunk - and thus avoid damaging their own (or anyone else's) health. Surely that's an app that even The Daily Mail would find difficult to criticise.

Even PM Gordon Brown also has his own app - the Number 10 offering includes photos, podcasts, tweets and other topical updates from the Prime Minister's office. As apps go, it's probably best described as an acquired taste but you can't say it's not furthering the cause of open government.

These apps are free to download - but about the other cost, you may ask: how much taxpayers' money is government splashing on this stuff? And shouldn't they be using our taxes to pay for...

...important stuff, like new schools and hospitals?

The truth is the money required to make apps really is very petty change indeed in Treasury revenue terms. A baseline price-tag for a not-entirely-basic app is around £10,000 to £15,000. Placed on the grand scale of government IT spending - Whitehall has a tech budget of £16bn annually - apps barely register, especially if you already own the data, and data is something the government is not short of.

But back to that Number 10 app - if there's going to be a sticking point defending public sector apps its name is Gordon Brown. Why should taxpayers have to cough up to fund the PM's personal propaganda?

While it's not free to create apps, it is a small price to pay for engaging more people in politics - especially younger people who are often all too apathetic about the subject but tend not to be so apathetic about technology. You don't have to like something to engage with it - often, quite the reverse is true - but you do have to know about it.

Brown's app aside, government apps often come with a public service agenda - they aim to have a positive social impact which, in the long run, could actually save the taxpayer money - by cutting joblessness or traffic jams, say, or reducing binge drinking. And if the Royal Navy doesn't have to pay for a big expensive TV ad-recruitment campaign because it's managed to fill its hiring quota with enthusiastic iPhone owners then ultimately that's good news for the taxpayer too.

But let's put the numbers aside for a moment - there's something more fundamental to consider: governments should be forward-looking. They should embrace proven tech developments when the people who vote them into office are doing so in their droves. You could almost say it's their civic duty to do so, to make sure they keep pace and stay relevant.

This is not posturing on tech's bleeding edge. This is not the government deploying a phalanx of driverless cars to encourage people to get out and vote. Commercial mobile phones have been around since the 1980s. Smartphones have been around since the 1990s. Even mobile apps are not as new a wave as you might think - downloadable apps have been around since the early part of this decade so you can't really accuse the government of jumping on a tech fad just to look relevant.

In this case, politicians are just moving with the times.

The iPhone may be a relative newcomer to the smartphone world but what a rapidly expanding world it is - 185,000 apps in Apple's store alone, with apps on many alternative platforms also mushrooming. Looked at on their own, iPhone users might still be a bit of a niche group but add in individuals on BlackBerrys, Android devices, Symbian mobiles and so on, and you're creating something that's accessible to a large swathe of professionals and young people. Yes, government has so far tended to start its app efforts with the iPhone but it has to start somewhere and clearly wants to go further.

Smartphone adoption rates are on the rise too: more and more mobile users are upgrading to these app-friendly handsets, and lower cost smartphones are being launched too - meaning more people will be able to afford to own a smartphone and, by extension, download free apps.

In the not too distant future, it's not stretching things to say the smartphones of today will be the everyday mobile handsets of tomorrow - it'll be the rule to own one, and therefore the rule to mess around with apps. Which means a government that's willing to explore what mobile software can do now is less likely to lag behind when the tech is as commonplace as the kitchen toaster. So I say again: how refreshing to see politicians thinking two steps ahead for a change.