'Biggest ever' web attack on BBC actually wasn't even close

NEW YORK -- Bringing down one of the world's largest websites by size and traffic, as it turns out, gets you noticed.

On the morning of New Year's Eve, the BBC's website suffered an extensive outage it initially blamed on a "technical issue." It was later reported by the broadcaster's own news division to be the result of a distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack.

WHERE IT BEGINS...

In total, the BBC's entire domain -- including its on-demand television and radio player -- was down for more than three hours, with residual issues for the rest of the morning.

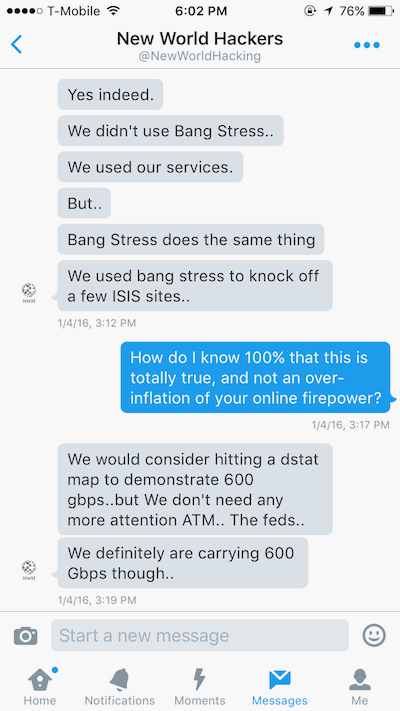

A group calling itself the New World Hackers claimed responsibility for the attack. A member of the group, who identified himself as Ownz but declined to use his real name, told ZDNet in a message at the time that the group had carried out the attack, calling it a "test of power."

The self-styled hacktivist told the BBC News in a Twitter message -- posted as a screenshot -- that the attack was "almost exactly" 600 Gbps in size. Ownz later reiterated the claim to ZDNet by providing screenshots we could not verify, purporting to show an attack of about 602 Gbps in size. The group also claimed that the attack's traffic came from Amazon's cloud service.

If true, the attack on the BBC would be almost twice the size of the largest web attack ever recorded; even attacks in the 300 Gbps range are uncommon because of the level of skill required to conduct such an attack.

But two weeks after the BBC attacks, the post-mortem is clear: The New World Hackers claims don't hold up to basic scrutiny.

'Nothing' on the radar

You would think that after such a big bang, someone might have noticed.

Of the many major network infrastructure and monitoring firms that we spoke to in the past couple of weeks, not one was able to see evidence of an attack that came even close to the claimed size of the attack on the BBC.

When asked about the reported attack, the BBC said it wouldn't comment further on the matter.

Security

DDoS attacks rely on pummeling a web server with so much traffic that it crumbles under the weight and stops responding. Smaller attacks are fairly trivial to carry out, and are used by many hacktivist groups to bring websites down -- often in protest -- for extended periods of time. Because of the size of the traffic needed to bring down many modern sites -- many of which come with systems that mitigate those attacks -- these attacks can be detected in real-time, and in many cases leave a trail of virtual evidence behind.

ZDNet has learned that industry sources, who did not wish to be named, are aware of attacks matching 600 Gbps which have been previously detected and privately reported. Attacks that big are rare, and are understood to be difficult to carry out.

But an attack of that severity has not been recorded in recent months, according to a trusted source at a major network and infrastructure monitoring company, who did not want to be named for the story.

We also asked network security firm Arbor Networks, which has visibility into about a third of internet traffic. When asked about the BBC attack, the company had no evidence to support the hacktivist's claims.

"We can't find any evidence of a 600Gbps DDoS attack taking place," said Darren Anstee, chief security technologist at Arbor Networks, in an email last week.

Anstee said attacks of that scale are possible by leveraging advanced reflection amplification techniques, but he would expect an attack on that magnitude to "show up" in its systems.

Et tu, Amazon?

The hacktivist's grandiose claim that it used Amazon's cloud service to conduct the attack was almost believable.

Following the attack, Ownz said that the size of the web assault was made possible by using at least two "Amazon servers." The hacktivist said the group has "ways of bypassing Amazon," referring to the company's systems which prevent web attacks from being carried out.

In a follow-up conversation last week, the hacktivist said the group "programmed a bypass linked to proxies" so that monitoring firms "wouldn't detect it anyway."

A source with direct technical knowledge of Amazon's systems and internal processes, who did not want to be named as they were not authorized to speak on the record, dismissed the allegation, saying that it "doesn't line up" with how Amazon's cloud service works.

Amazon's Web Services (AWS) has a number of manual and automatic systems and measures that stop denial-of-service attacks from being launched. In the vast majority of cases, attacks don't leave the company's servers. In a scenario where an attack is launched from its service, Amazon can just as quickly stop it in its tracks.

The retail and cloud giant has made similar statements before regarding claims of groups using its cloud platform for nefarious reasons.

A spokesperson for Amazon did not comment on the BBC's case.

Khalil Sehnaoui, a security researcher and founder of Krypton Security, also poured cold water on the group's claims.

In an email, he said a botnet would be almost out of the question but it would be possible for a more advanced form-based attack or an application layer attack rather than a botnet.

But even if the attackers were able to launch a successful attack that left Amazon's servers, it wouldn't take long for Amazon to notice, he said.

To conduct an attack that big would require a botnet, a collection of infected devices that are turned onto a single target to overload it with traffic. Amazon has been tapped by botnet controllers before, but only in a handful of cases. The last known case of an Amazon botnet was two years ago.

An older attack carried out by the group was not considered "sophisticated in nature," according to one source who spoke to us, who was actively involved in mitigating that previous attack.

The burden of proof falls squarely on the hacktivist group, which failed to back up its claims after repeated requests, leading us to alternative explanations.

Rent-a-refresh, refresh, refresh?

If not Amazon, then how?

The group claimed to use a proprietary, custom-built tool -- a "stresser" or a "booter" -- which was built from the ground up in just two weeks, said Ownz. The hacktivist sent us a number of screenshots -- purporting to show the stresser in action -- which could not be verified as authentic.

If true, it wouldn't be the first instance of a hacktivist group using their own tools.

When the now-infamous Lizard Squad took responsibility for taking down a number of websites, the group used its own proprietary Lizard Stresser tool, which relied on compromised home and office routers to launch attacks. The stresser could take almost any website offline for hours or days at a time.

However, it seems unlikely, given that it's easier and often more effective -- both for power and cost -- to rent an existing stresser. There are many stressers available to anyone who wants to pay, but generally require a login provided by the owner.

However, the source who successfully helped mitigate a similar attack by New World Hackers on their company said that -- based off an analysis of the attack -- the group likely used a tool called Bangstresser -- apparently contradicting Ownz's claims that it developed its own web interface, which we previously reported.

The purported owner of the Bangstresser tool said in a post that users could theoretically buy enough firepower to conduct an attack at a size of more than 400 Gbps with a so-called "layer 4" attack. And that firepower can be cheap, too. In most cases, you can sign up using bitcoin, which makes it almost untraceable, and perfect for the up-and-coming hacker group.

When asked, Ownz sent screenshots suggesting that the group instead used the stresser to conduct "layer 7" attacks, which can be difficult to detect because the server treats the traffic as ordinary web visitors.

"Any attacks are hard to protect against because it is not possible to drop all incoming traffic on port 80 because doing so will prevent the server from serving legitimate traffic," said Sehnaoui. "Since usually the attacks are coming from hundreds or thousands of different [IP addresses] all belonging to unsuspecting victims that make up the botnet, tracing IP's will get you nowhere."

In other words, the attack is like hitting refresh on your browser, just thousands of times a second.

One well-known hacktivist, The Jester, said however that it was "entirely plausible" that the hacktivist group launched a massive attack by purchasing access to "an already established botnet service."

He said "skids" -- a term often referring to teenagers who would use pre-made tools to automate attacks -- "use [botnets] to hit other gamers."

Following the attack on the BBC, the hacktivist also targeted other sites, including the campaign website of Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump. But also in the aftermath of the attack, the group stirred controversy when one of its members allegedly went rogue and took down an activist site belonging to the Black Lives Matter movement.

"TangoDown," the group tweeted, announcing the site's shutdown following a sustained port 80 attack. But the backlash was enough to force the group to "knock [the rogue member] offline" following the incident, said Ownz.

The Jester, who first coined the "TangoDown" phrase when he would attack and bring down jihadi websites, wasn't happy at the overuse of his term.

"'Tango Downing' used to be a lot cooler before Anonymous skids learned how to hit F5," he said in an email.

In the attack's aftermath

The BBC's website returned after about three hours, but it would've taken longer without help.

According to a blog post by Netcraft, a UK-based internet services company, the BBC restored service to the new, non-legacy portion of its website with help from Akamai's content delivery network. By moving the attacked block of internet addresses to Akamai, the service was mostly back to health by the afternoon.

Some publications were quick to capitalize on the news of the "biggest-ever" web attack. Some hedged their bets in the face of a lack of evidence.

But the absence of convincing proof, coupled with a barrage of misleading statements, suggests that the biggest web attack in living history was -- for all intents and purposes -- nothing more than a publicity stunt from a faceless group.

Sehnaoui said the group is likely "just skids having some fun and trying to gain some publicity," adding that taking down sites like the BBC is "well worth the few dollars they would have spent to rent a botnet" for the headline.

Ownz said in a message just days after the BBC attack that they "aren't really attention seekers."

In fairness, they caught our attention.