The Boy Who Could Change the World, book review: A tantalising legacy

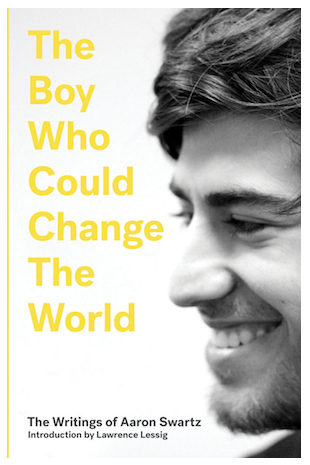

The Boy Who Could Change the World: The Writings of Aaron Swartz • Foreword by Lawrence Lessig • Verso • ISBN: 978-1-78478-496-6 • 360 pages • £15.99

What most people know about Aaron Swartz is that he stole (if you're a journal publisher), copied (if you're a journalist being neutral), or liberated (if you're a hacker or work for Google) millions of journal articles from a service called JSTOR and, under threat of prosecution, committed suicide at 26.

A taste of the internet's reaction to his death can be seen in the trailer for the 2014 documentary film about his life, The Internet's Own Boy (YouTube). As this and the obits that followed his death in 2013 made plain, Swartz's short life was crammed with an unusual amount of incident. He helped create RSS, Creative Commons, SecureDrop, and Reddit, campaigned against SOPA, and was a research fellow for Lawrence Lessig's lab on institutional corruption.

Through all that, as the recent book The Boy Who Could Change the World: The Writings of Aaron Swartz makes plain, he was also a prolific writer and blogger on all sorts of topics.

The book is divided into six sections, each of which represents one of Swartz's key interests: free culture, computers, politics, media, books and culture, and 'unschooling'. Each section includes essays and book reviews, both short and long, each of which in turn is stamped with the date of posting and his age at the time, as well as an introduction from a well-known friend such as Cory Doctorow, James Grimmelmann, and Seth Schoen. There aren't many 14-year-olds whose book reviews are worth including in an anthology, but then, there aren't many 26-year-olds who've written enough intelligent material to fill a book.

Political interests

Swartz was often described as a computer genius, but what this collection of writings makes plain is that he rapidly became much more interested in politics. His younger pieces -- book reviews, meditations on 'unschooling' (the 2000s equivalent of the 1970s Summerhill), and ideas for using computers to provide accessible tools -- give way in his later writing to explications of how Congress works, the US judiciary's First Amendment "blind spot around copyright", and how to make change happen. His piece on why open data doesn't create transparency is a particularly good balance to some of today's hype.

The publicity surrounding the prosecution made famous one piece of writing to which his name was connected: Guerilla Open Access Manifesto. It appears in this volume with a note explaining that there is uncertainty about its authorship. Swartz published it on his website, and although he later withdrew it the government viewed it as evidence that Swartz intended to release the JSTOR articles to the public.

In the few years since, and partly as a response to Swartz's case, open access has become much more accepted as a necessity for scientific progress. Compare, for example, the 2011 stories about Swartz's arrest to the last two weeks' coverage of Sci-Hub, the repository of 47 million journal articles (and counting) set up (also in 2011) by the Russian neuroscientist Alexandra Elbakyan.

In the book's final piece, 'Legacy', Swartz writes (at 19) that a person's impact on the world should not be measured by what they accomplished -- their work may have benefited from luck, good timing, and other people's choices. Instead, it should be measured by what things would be like if you had never done it. Few of our usual heroes survive that measure.

More book reviews