TigerText can erase sent text messages. Is it really the 'perfect app for cheating'?

Yeah, that's what I thought.

Those text messages? Now bygones. The answer from here on out: TigerText.

While traditional texts live a second life on your carrier's server, long after you hit erase on your phone, TigerTexts are deleted at a time of your choosing, between one minute and one month after they're read.

Think of it as the morning-after pill for your messaging. Or, if you're not inclined to that metaphor, imagine texting on an Etch A Sketch. You read it, and then--shake!--it's gone.

The app was released last week for the iPhone, and the company expects to roll out apps for Blackberry and Android in the next few weeks.

You can give it a shot with a free 15-day, 100-text trial. If you like it, it's a $2.49 monthly fee for unlimited texts. (When you use TigerText, your carrier's text fees won’t apply, since they’re technically not phone texts.)

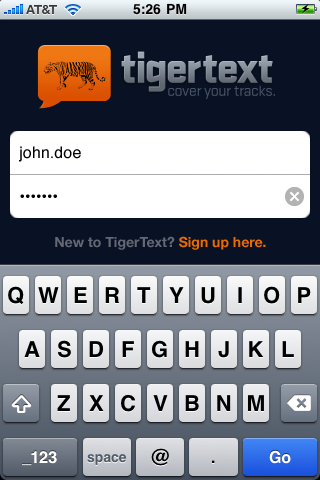

Here’s how it works. Other than the hue, the app looks just like conventional iPhone texting. The difference is that the settings prompt you to select a time for your messages to be deleted. The minimum allows the message to live for 60 seconds after the intended recipient opens it; the maximum allows it to live for 30 days.

Although users on both side of the conversation must have the app, it's the sender of the message who controls when it is deleted.

The message completely circumvents your phone's server by instead transmitting through TigerText's server. If, for instance, you select two hours for the lifespan of the message, after two hours, it will be deleted from the sender's phone, the recipient’s phone and the server -- forever.

There is a countdown to show how much longer the message will exist on this planet, and—poof—after it’s gone, there are tiger paw prints in its place. (Which, you must admit, are adorable.)

Here's a look at the app:

Time magazine took an easy shot at TigerText by making the obvious link to Tiger Woods' philandering -- calling it "an iPhone app for cheating spouses" -- but the app's implications go far beyond illicit affairs.

What about using it on your corporate-issued smartphone?

"Instead of loose lips, we use the term loose thumbs," said TigerText founder Jeffrey Evans. "And everyone has loose thumbs at some point. 'I hate my boss' -- you can say that, and we've all said that. But if you text it and your employer finds it, your career is over."

Evans said an increasing number of employers are searching the Internet to see what they can find out about a potential employee.

Whether it's the case of former Detroit mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and his infidelities -- which were revealed in text messages between him and his former top aide -- or the case of Sgt. Jeff Quon of the Ontario Police Department in California, who sued after the department read transcripts of texts from his government pager, saying it violated his Fourth Amendment rights, the issue of privacy and texting has reached a critical point.

In December, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed to take on the Ontario case and decide whether the department violated Quon’s privacy rights. The court's decision may send a broader message about privacy in this digital era, especially for workers communicating electronically using their employers' phones.

Evans says the legal community is applauding TigerText. He says one attorney told him, "I can't say how many times my clients' text messages have caused problems for me."

"Fortunately, we live in a country that doesn't believe that's the way things should work," Evans said. "I certainly feel like the government is getting more intrusive, not less."

Detroit mayor Kilpatrick and Ontario officer Quon surely would have been better off—at least in the texting cosmos—if they'd had TigerText.

But would we have been better off?