To design better schools, get better data

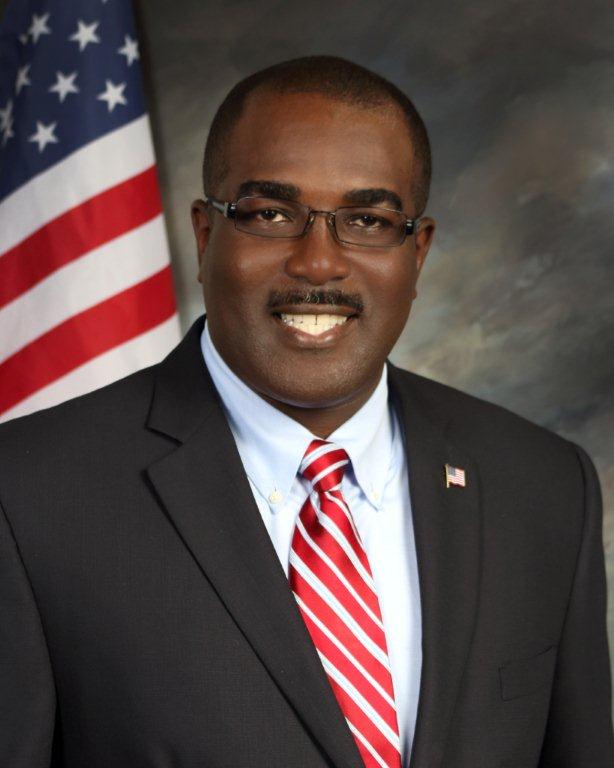

They don't call him Stan "Data" Dobbs for nothing.

A former logistics commander with the U.S. Navy, Dobbs now consults to school districts in Hayward, Calif., and to the south in Monterrey. In these places, military base closures have crippled many schools, draining students and finances, too.

The secret of his approach is tracking and quantifying school district resources to better understand their fiscal challenges and potential remedies, budget-wise. That includes tracking kids, whose average daily attendance rate, or ADA, generally determines how much government money is allocated to each school.

Based on the numbers, Dobbs works to strengthen a district's "bottom line" using accurate ADA numbers, grants, bonds and the like. Then he shows municipalities how to "leverage their assets" -- for example, by leasing shuttered facilities for commercial uses, such as grocery stores, which benefits the district and residents alike.

Data: Essential to school design

The "Data" Dobbs success stories are impressive, as I heard with a group of business leaders at a Newark, N.J., breakfast organized by Andrew Frazier's Brain Trust Initiative. In fact, data is increasingly harnessed in innovative ways to make schools better.

Number-crunchers like Dobbs are a great allies for architects.

One of the latest techniques is geospatial analysis, which uses GIS software to "geo-code" student populations. This is a powerful technique, says Adam Lubinsky, managing principal with New York's WXY Architecture + Urban Design, which can help address inequities in scholastic resources and create new, promising opportunities for districts to reinvent.

One of Lubinsky's projects was on view at a current exhibition on K-12 architecture called The Edgeless School, at New York's Center for Architecture. (Both are clients of mine, by the way.) The project, REED Academy in Oakland, N.J., is a state-of-the-art elementary school for students with autism spectrum disorder.

In this case, the data behind the design is from applied behavioral analysis, or ABA, which the group Autism Speaks calls "a scientifically validated approach to understanding behavior and how it is affected by the environment."

Special-needs schools, too

Using glass and a careful layout, REED Academy "blurs the distinctions between learning needs approaches and environments," says Lubinsky. By removing the distinctions between these spaces, research shows, the school better meets needs of young autistic people. State officials see REED as a prototype for more schools dealing with autism, attesting to its success.

There are other, more controversial uses of data that may not help architects.

SmartPlanet's own Sarah Korones recently reported on the use of RFID tagging in Texas schools, mainly to catch kids playing hooky. Two San Antonio schools now require students to wear ID cards with chips, so the principal can track their locations. Districts in Houston and Austin are doing the same.

Architects immediately see a potential bonanza: By tracking student body movement, you could identify circulation bottlenecks and better understand how school buildings, rooms and corridors are used. Stan "Data" Dobbs could use the information to confirm ADA attendance rates, the basis of federal funding.

Unfortunately, that's not how it's being used, and actions by the American Civil Liberties Union to promote "chip-free schools" may stem the practice.

Data for interior design

As the exhibition Edgeless School shows, design for learning can affect not just district-wide planning or building design, but even the choice of colors and shapes inside our schools.

The idea of edgeless, says the curator Thomas Mellins, can be glass walls at at the REED Academy, but it can also be using indoor-outdoor classrooms, interconnected rooms and corridors, and flexible, multiple-purpose spaces.

Lubinsky points to WXY's design for the Day School at Christ & St. Stephens, a pre-K in Manhattan, where color is used as a learning tool. Color-coded stepped seating leading to its reading nook -- grey for climbing and circulation, teal blue for sitting -- teach kids their boundaries and what behavior is appropriate. The interiors also use tonal palettes, such as its Dutch-style bathroom tiles, sourced in 13 different shades of white.

The firm's research has shown that tonal variation encourage young students to add color and texture to their work in the classroom, fostering imagination and also promoting abstract thinking.

Yet the use of better data in school design is still an experiment in many ways, according to Edith Ackermann, a visiting scientists at MIT who served as senior research consultant for the exhibition.

"There is much talk about 21st-century skills these days, and much research being done to redefine what today’s youngsters ought to know in order to be active and successful in tomorrow’s world," says Ackermann. "What is less clear, however, is the built environment's role in helping children find their ways—and grounds—under the conditions of this uncertainty."

------

Note: The exhibition The Edgeless School, Design for Learning is open through January 19, 2013, at the Center for Architecture in New York.

This post was originally published on Smartplanet.com