Verizon's secret data order timed to expire, but NSA spying to carry on

On Friday at 5 p.m. ET, an order that allowed one of its intelligence agencies to vacuum up Verizon customer records en masse would have expired.

Most will admit, considering the past month's worth of revelations, allegations, conspiracies, and denials, that it would a gutsy move on the part of the White House to renew the order.

But it was, at the same time, arguably a necessary one.

"The Government filed an application with the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court seeking renewal of the authority to collect telephony metadata in bulk, and that the Court renewed that authority," the statement from the Director of National Intelligence James Clapper said.

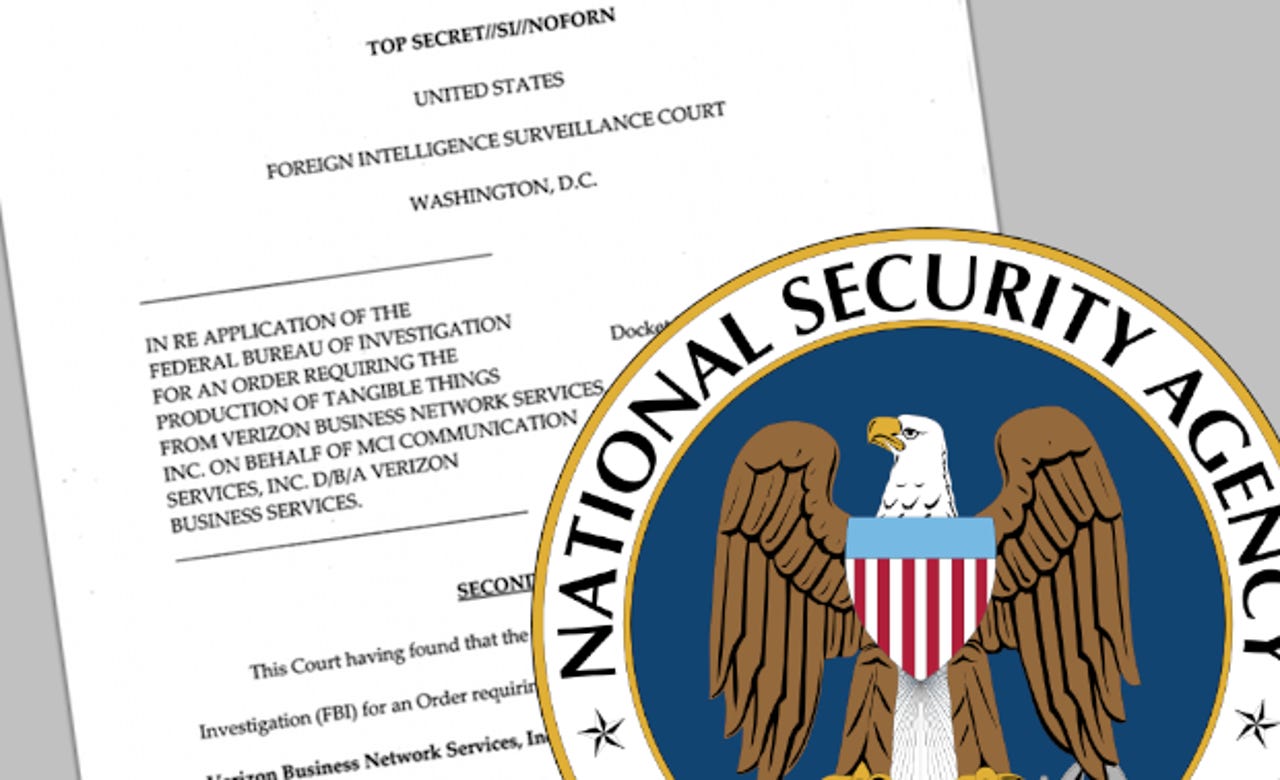

This whole surveillance saga with the U.S. National Security Agency began with a secret court order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), authorized under its namesake law in 1978. From there, the NSA has been sapping every "tangible thing" from the cellular provider under Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which includes all call details or "metadata" relating to calls created by Verizon between the U.S. and abroad, or within the U.S., including local calls.

And that order alone, as innocuous as a legal document can look like, was to set the way for a vast spying scandal that would blow the lid off diplomatic and political relations worldwide, threaten transatlantic trade talks, and strain former Cold War peace channels.

Not to mention, perhaps more closer to home, have half the world on edge.

This order, dated April 25, 2013 — will be declassified in 25 years (2038) from the date it went into effect. But it was in fact brought into force about seven years ago. Every 90 days, the same order would be issued to Verizon so long as the judges on the FISA court agreed.

Other companies, such as AT&T and Sprint, reportedly received similar orders, though under FISA they are not allowed to say if they have been.

But because of the nature of these laws, the U.S. government imposes gagging orders and free speech restrictions on companies. In a rare show of faith by the U.S. government, politics aside, the Director of National Intelligence noted that on June 6, certain parts of the "telephony metadata collection program" was declassified. Besides another Snowden-like leak, there's not much in there.

Had the order expired, the U.S.' intelligence machine not only begins to crumble, but its head falls clean off.

In reality, the likely — albeit depressing scenario — is that these spying programs will continue. In the grand scheme of things, knowing for a fact over presumptions and guesswork doesn't vastly change the landscape we have found ourselves in over the past few years. We have known our governments are spying on us — in some way, shape or form — and we can presume that other governments, particularly our respective allies, have a similar capability.

Rep. Jim Sensenbrenner (R-WI), the author of the Patriot Act, told the Guardian on Thursday: "I would advise the president to reconsider his misinterpretation of Section 215 and rein in abuse."

There has been a disconnect between the U.S. government and its lawmakers. Almost a "chicken and egg" scenario. Who is ultimately to blame: the lawmakers for creating vague legislation, or the White House for taking the spirit of the law and bending it to the greatest degree?

Ending a vast and widespread surveillance program will be an admission of guilt, and as though the U.S. government did something wrong.

And if, in President Obama's words, "you can't have 100 percent security and also then have 100 percent privacy and zero inconvenience." But if you could choose between an absolute of either, which would you take?

Updated at 5:30 p.m. ET: with statement from Director of National Intelligence. ZDNet's Rachel King has more.