Vista Mythbusters #6: Is Vista really more secure?

Myth: Microsoft touts Windows Vista as the most secure Windows ever, but the changes are mostly cosmetic. In addition, the new User Account Control feature is so annoying that most Vista users will simply turn them off.

Reality: There's a lot more to security in Windows Vista than just a few dialog boxes, and anyone who takes advantage of all the new features will certainly be more secure. But no one can say for sure how effective the new tools will be for the broad community of Windows users until Vista is widely available.

User Account Control is the security star of Windows Vista. It gets the lion's share of the publicity, and through Beta 2 the reviews weren't good. In early builds, beta testers complained that User Account Control was annoying and confusing, overwhelming users with a blizzard of consent dialog boxes for seemingly simple actions.

In Vista Release Candidate 1, UAC has been toned down dramatically. I've put together an image gallery that shows what the security features in this near-final version look and feel like so you can see for yourself. If you install RC1, you'll see UAC prompts only when you actually try to change a system setting, install a new program, or access files and folders in protected locations. In Beta 2, for instance, simply opening Task Manager required consent via a UAC prompt; in RC1, Task Manager opens as usual, and consent is only required if you want to see processes that are owned by a system account or by an account other than the current logged-on user. After initially setting up a new PC, most users will barely notice UAC. Microsoft is hoping that will convince most users to leave this feature enabled.

But what about the larger picture? Do the new security features help? The answer is a qualified yes.

The biggest weakness in Windows XP from a security point of view is its poor support of limited (also known as standard) user accounts. Using any operating system in a standard account is a smart security practice, because security exploits typically work with the credentials of the logged-on user. A standard user who gets tricked into clicking a link that leads to a hostile web page or installing a piece of malware can't alter system settings. But anyone who's tried to run Windows XP using a limited account has probably given up in frustration within a few hours. Vista changes that experience architecturally, by virtualizing the directories and registry keys where programs are allowed to write. (See this page for an example.)

Many programs that fail when run under a standard user account in Windows XP run just fine under Vista, thanks to this change. In homes and on business networks, that means administrators (including parents) can set up users with standard accounts and severely limit the damage they're able to do, even if an attacker can convince them to try to install a program.

The companion piece to UAC is the new Protected Mode in Internet Explorer 7, which shifts browser add-ins into a sandbox and makes it more difficult for them to access system locations. An administrator who carefully sets up a new Vista system can protect users from themselves by restricting their ability to install malware or make changes that compromise the system. [Update: As commenter PB_z notes, Protected Mode IE runs the entire browser process in this sandbox, not just add-ins.]

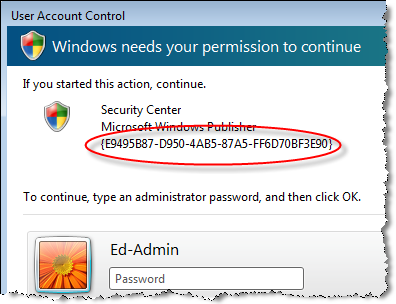

But UAC and the new IE7 security features only ask questions; they don't provide detailed information that nontechnical users can rely on to make decisions. As images like this one show, a user who is confronted with a UAC dialog box often has only a filename or a snippet of technical gobbledygook available on which to base a decision. That raises the bar for scammers and attackers who use social engineering techniques, but only slightly. And critics say, with some justification, that users who leave UAC enabled will simply learn to click yes automatically, undoing most of the security benefits.

Corporate users have a whole toolbox of additional security options as well, including Bitlocker drive encryption, better support for authentication through Smart Cards, and policies that can lock down a system without locking out users.

Will Vista be more secure? Certainly. But it will be months, maybe a year or more, before we know how much of a difference it really makes.

For the introduction to this series, see Vista Mythbusters #1. For all posts in this series, see this page.