Yoti can guarantee your identity online, but sometimes you just want to fake it....

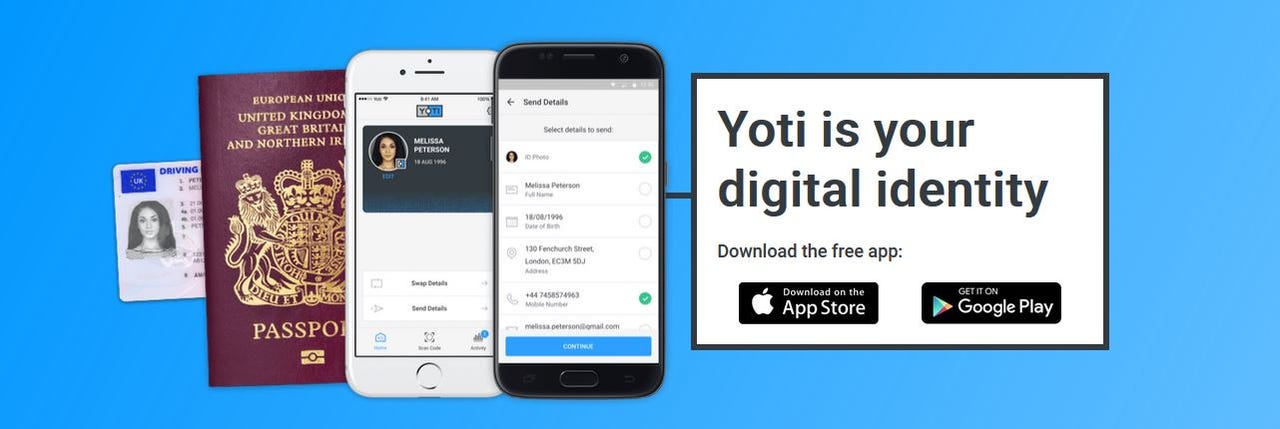

It's hard to establish a successful online identity system. Even after 40 years, nobody has managed it. Microsoft has tried three times: its first effort (Hailstorm) was shouted down; its second (CardSpace aka InfoCard) failed, despite being very well thought out; and its third (U-Prove) hasn't been launched. This is a market that is now being approached by new companies such as Yoti (Your Own Trusted Identity), which I posted about earlier. See: Yoti aims to provide everyone with a biometric digital identity that works via a smartphone app

The lack of a successful trustworthy identity system forces people to use different passwords for dozens of different websites and services, or in some cases, a third-party system that compromises their privacy. Examples include Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Twitter and similar accounts.

To provide the level of trust required for serious applications, an identity system must link its IDs to unique users whose identities have been confirmed, usually by biometrics (fingerprints, voice prints, iris scans) or by state-approved documents (passports, driver's licenses) or both. However, an ideal system would also allow users to be anonymous or even pseudonymous.

This may sound contradictory, but it's not. Identity systems are mainly used for two different purposes: identification and authentication.

In many cases, companies ask for identification when what they want is authentication. For example, if you're using a credit card, merchants don't need to know who you are. They only need to know that they'll get their money. If you're buying alcohol or a senior citizen's ticket, they only need to know that you are over 16, 18, 21, 60 or 65, depending on the particular age requirement. Somebody who is checking your age should not be able to see the other data on your passport, driver's license or other identity card. They don't need to know your name, where you were born, when your passport expires, and so on.

There is also a need for pseudonymous and therefore multiple identities, because lots of people use two or more names. Many women use both their maiden names and their married names. Many Chinese people have both English and Chinese names. Many writers, artists and performers have both personal (birth) names and stage names. Many online users are better known by their "handles" than by their real names

An identity system should allow users to present whichever identity or persona they want, without them having to take out multiple identities.

I talked to Robin Tombs, Yoti's co-founder and CEO, to find out how closely it approached these ideals. The short answer is "not very," but it will get closer over time.

"Simplicity is important," says Tombs. "We thought long and hard about it, and we talked to a lot of consumers, and the ability to have lots of Yotis would confuse people. This is probably, at some point, something we should allow, but initially we want to make it a simple message for people."

Tombs says Yoti will be able to handle people who have both a married name and a maiden name - it's not in the first version - and someone with two passports could take out two Yotis. But he doesn't want to introduce complexities before users need them.

Anonymity is a possibility, but that depends on the company that's asking for authentication, not the user who is presenting it.

"We have no idea if you're using the system. If you use Yoti with another individual, we know nothing," says Tombs. "We just issue receipts to the willing counterparts. If it's with a company, we know that a name has gone to, say, Barclays Bank, but we don't know whose name. We don't need to know that information, so it's best if we don't know it. We've designed a system that prevents us from knowing it, so that you and Barclays can trust the system."

Barclays pays for the service, and the fee is cheaper than the type of database check that financial services usually use. In other words, Yoti isn't a Google-type solution where users trade data for a free service.

The result is that Yoti is better for consumers than traditional identity systems. However, it still gives businesses a lot of control. They can demand information whether they need it or not, and you only have two choices: provide it, or go elsewhere. You can't bargain about what you're giving up in exchange for what you're getting. As a result, you could end up worse off.

Yoti makes sense in transactions that are tied to real-world applications, such as guaranteeing a bank card, a loan application or a tax filing. It would also make sense for verifying Twitter or Facebook accounts based on real or pseudonymous (stage) names, where you might otherwise have to provide a photograph of your passport or other ID. But in a lot of cases, it doesn't.

For example, if a company or a website wants your name and email address in exchange for something you want, you can easily provide a false name and a throwaway email address. You don't need to divulge your real identity.

Tombs understands the issues, and perhaps he can establish a simple system before expanding it. Simplicity should have more appeal than CardSpace/InfoCard, which - like other attempts at a federated identity system -- was too sophisticated for an audience that never understood the problems it was solving. But based on previous experience, it still won't be easy....