The Mac at 25: GUI battles in business

It's near impossible for new computer users today or even a decade ago to understand what the big deal was about the Macintosh. After all, the most base cell phone in your pocket offers up a graphical user interface of menus and objects. However, 25 years ago, GUI was a firing offense in many offices.

The features and design of the original 128K Macintosh ran counter to everything that computers were supposed to be: expandable, boxy, and supporting a 5.25-inch floppy drive. This kind of machine wasn't only what IBM offered, it was what Apple had built its success upon, the Apple II.

Instead, the Mac was portable (it had a built-in handle — something that desktop computers still could use), it was closed and opening it up yourself was a violation of the warranty, and it came with a small "high-capacity" floppy drive that used expensive 400KB diskettes. And most folks forget that the Mac was the first personal computer to come out of the box with networking built-in: AppleTalk.

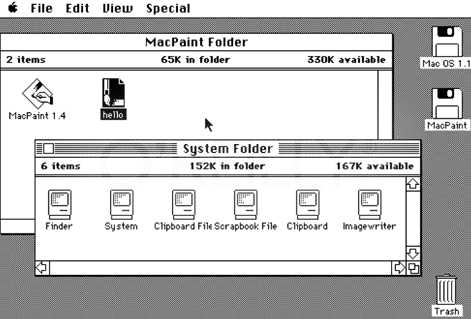

Then there was the interface. Instead of a DOS prompt, whether Apple DOS or Microsoft's PC-DOS, the Mac had QuickDraw, the Finder interface and MacWord and MacPaint and MacDraw programs. It was all about images and menus and manipulating a virtual desktop with a mouse.

This GUI was disruptive in several ways. Today, we conceive of the screen as the final presentation vehicle for data, while back then, it was hardcopy. What the Mac produced was compelling — typography, images and complex charts — even on black-and-white dot-matrix printers. When the LaserWriter and PostScript output hit the platform, the gap widened.

I heard executives who were exposed to the Mac ask their corporate IT directors why the big-budget big iron couldn't make a simple chart like the Mac. There was no easy answer, since the Mac was designed from the ground up to deliver graphical information and the mainframe wasn't.

At the same time, the concept of the GUI was under attack. Many IT managers and bosses considered the GUI a productivity killer. Instead of entering data, users were spending valuable time choosing how the data would be formatted. I recall that the Mac and Windows were decried as a time waster by Randy Fields, co-founder of the Mrs. Fields cookie empire.

Microsoft Excel and Word were Mac-only back then. Windows was just starting and didn't work well. And besides, no business user would want it or should run it, right? GUI made computing "too easy," some IT staff would say.

Eventually, Windows was refined and the benefits of GUI computing were validated even in the PC community.

Still, the cultural differences between the PC and Mac communities are deep and remain to this day. Here's a recent example: At the 2006 Macworld Expo in San Francisco, Steve Jobs introduced the iWork suite, which contained the Pages word-processor application.

Several PC-centric colleagues saw the demo and wondered about the reaction of Adobe and Quark to the new competition. In their experience, the power and deeply integrated graphical capabilities found Pages must make it a professional tool. It couldn't be for you and me. Their imagination was in the box of Microsoft Word and Windows XP.

I replied that Pages wasn't any sort of competition to InDesign or QuarkXpress. Rather, Pages was simply an expression of what a word processor should and could provide in the graphics department. And that creating these kind of documents with sophisticated integrated graphics was an expectation of Mac users.

As it was back in 1984, so it is today. Some folks don't get the Mac or the all the possibilities of the "simple" GUI.