The malware numbers game: how many viruses are out there?

How many strains of malware are in circulation right now, for Windows PCs, Android devices, and Macs?

That seems like a straightforward question, but the answer is far from simple. And the number might be a lot lower than you think.

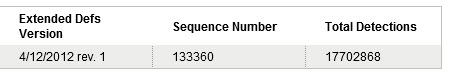

If you check with the leading security companies, you might be tempted to pick an answer in the millions. After all, that’s how many listings you’ll find in the definition files for common antivirus programs. At day’s end on April 12, for example, Symantec published the summary shown below, noting that its latest Virus Definitions file contained 17,702,868 separate signatures.

Oh my. 17.7 million? That certainly sounds like a very big number. But before you get swept away, it’s worth taking a closer look at what it really represents.

Eight days earlier, on April 4, that same Norton/Symantec definition file contained 17,595,922 separate detections. With 106,946 additional definitions in a mere eight days, you’d probably conclude that malware is out of control.

Because the Norton brand name is primarily associated with Windows PCs, you’d probably also assume that all of that activity was aimed at the Windows platform.

And you’d be wrong in both cases.

Definition files are a great way of assessing the degree of activity at a computer security company. They vaguely measure the current intensity level of the cat-and-mouse game between malware authors and security companies. But counting signatures says nothing about what’s new.

I took a closer look at the Symantec definitions for that week and found a very interesting story.

Symantec, to its credit, publishes detailed information about what’s in each new definition file, including what’s new. On any given day, it displays the total number of new and revised detections, followed by their details, like this:

In the eight days between April 5 and April 12, only 12 new detections were added to Symantec’s certified definition file, with six of them added on a single day, April 10. Here’s a breakdown:

- Three were generic detections for malicious packages (Packed.Generic.360 through .362). These aren’t really new strains of malware, only new forms of packaging. The accompanying writeup calls each one a “heuristic detection for files that may have been obfuscated or encrypted in order to conceal themselves from antivirus software.”

- Four are generic detections for existing fake antivirus packages (Trojan.FakeAV!gen90 and gen91, SmartAVFraud!gen2, and SecShieldFraud!gen5). These are also heuristic detections, designed to identify rogue anti-malware programs by their behavior rather than by their ever-shifting content.

- Two were aimed at Android-powered devices: Android.Tigerbot and Android.Gonfu.D are both backdoors found in malicious Android apps.

- One new entry is simply called Adware.SafeTerra, with no associated description.

- One new entry is for something called Trojan.Darkshell, which has only a vague description (“may perform distributed denial of service attacks”).

- One is the infamous Flashback, for Macs, formally known as OSX.Flashback.K.

The total number of named entries listed in the summary of those definition files during that period was 303—12 new and 291 revised. So where does the 100,000+ number come from? It appears to be a count of individual pieces of identifying data—signatures—associated with those named entries. Counting every signature is an easy way to get to an impressively large number, but it isn’t an accurate way to asses the current threat landscape.

That list includes a lot more than malicious software, too. Categories include Adware, Hack Tool (many of which are legitimate), Joke, Misleading Application, Potentially Unwanted App, and Security Assessment Tool. When I excluded those categories, I ended up with only 213 named entries in the Trojan, Worm, and Virus categories.

I was surprised to find that many of the definitions on this list are for very old pieces of code. During this one-week period in April 2012, Symantec updated its definitions for the following pieces of ancient malware and bumped up the counter in its definition files accordingly:

- The SubSeven Trojan, which was a big deal in the late 1990s but was officially shut down in 2003

- W32.Chir.B@mm, a mass-mailing worm from 2002 that targets Internet Explorer versions 4 through 5.5

- Spybot, a family of worms that spread using the Kazaa file-sharing network and a variety of Windows 2000/XP flaws that were patched in 2003

- Netsky, a 2004-vintage mass-mailing worm

- Mydoom, another mass-mailing worm that spawned one of the first botnets; it was programmed to do most of its damage in February 2004 and fizzled out within a few years

In addition, these April 2012 definition files include multiple revised detections for Waledac and Rustock, the Trojans responsible for two prolific spam botnets that were decisively shut down in February 2010 and March 2011, respectively.

For each named entry, Symantec includes the date when that entry was first added to its definitions list. Out of the total of 213 new named entries on the list, more than 85% were from 2010 or earlier. Only 31 entries were discovered in 2011 or 2012. And one-third of those were from non-Windows platforms.

Two of the recent samples were for OS X—the original OSX.Flashback, from last fall, and the newer OSX.Flashback.K, which wreaked havoc on Mac owners over the past month.

Most interestingly, eight entries on the list—more than 25%—were for Android-related malware. Given the size of the Android installed base and the lack of any central control over Android app markets, that shouldn’t be surprising. On its Latest Threats and Risks list, Symantec includes writeups for more than 80 Android-related programs, most classified as Trojans or Spyware. That's 11% of the total of 720 items on the list.

To make sure those numbers were representative, I looked at the Symantec definitions database for the entire month of March. In all, 66 new named entries were added to the list, or about two per day. Of that total, 36 represented new, named Trojans, viruses, and worms. Five of them were aimed at Android devices, one targeted OS X (no, it wasn’t a Flashback variant), and there was one new entry each for Symbian OS, Linux, and an Adobe Flash Player exploit.

In its 2011 Security Intelligence report, released earlier this year, Microsoft security researchers noted the problem with trying to measure the threat landscape by counting unique malware samples:

Ever since criminal malware developers began using client and server polymorphism (the ability for malware to dynamically create different forms of itself to thwart antimalware programs), it has become increasingly difficult to answer the question “How many threat variants are there?” Polymorphism means that there can be as many threat variants as infected computers can produce; that is, the number is only limited by malware’s ability to generate new variations of itself.

If you look carefully at the Windows malware landscape over the last 10 years, it’s apparent that a relatively small number of families are responsible for almost all the damage we’ve seen. I’ll look more closely at those families, and the evolution of Windows malware, in a follow-up to this post.