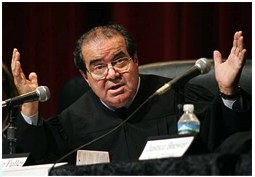

Free speech wins privacy tug of war; Law students school Scalia

As a newspaper journalist, I took pride in my abilities to dig through public records, sniff around court documents, dissect police reports and, yeah, even tap a handful of unconventional sources for the really-hard-to-find details about someone - all under the protections of the U.S. Constitution.

So, it comes as no surprise to me that a Supreme Court Justice - who created a stir when he said earlier this year that some proposed online privacy laws might be unconstitutional - ended up being the target of a law school class assignment to prove the professor's point, according to an entry on the Above the Law blog. The class was given the assignment of finding out as much information as possible about Justice Antonin Scalia on the Internet. What they came back with was 15 pages of information ranging from the Justice's home address and phone number, the types of movies he likes, his favorite foods and pictures of his grandchildren.

Ouch. Feeling a bit different about rights to privacy there, Justice Scalia? As it turns out, no. He hasn't changed his position.

When he spoke in January at the Institute of American and Talmudic Law's midwinter conference on privacy issues, he said that there are basically two types of personal data - confidential information such as medical records and information that may be personal in nature but also is public and accessible.

Technology, he said, may have made information easier to find but the idea that every fact about a person's private life be protected - as a matter of law, that is - is "extraordinary," he said. The Associated Press reported him as saying, at the time:

Every single datum about my life is private? That's silly.

He's right. It is silly.

I'm all for maintaining a certain amount of privacy for myself and my family. But I also recognize that there are certain details that are not private - no matter how flattering, embarassing or simply boring they might be. Birth records, property records, court records. Anyone can access them. There's no hiding them.

The other tidbits of information about us - what are kids look like and where they go to school, our favorite vacation spots, our employment status and even a favorite Starbucks drink - are largely available because we've put them out there. Facebook, Twitter, MySpace, Flickr, YouTube - it's all there because we put it there.

For example, If a stranger on the street came up to me and asked me how my trip to Vegas was last week, I'd be freaked out about how they knew that. And yet, I thought nothing of posting a few "Having fun in Vegas" Twitter tweets and Facebook status updates while I was there.

Again, I'm not anti-privacy - by no means. But I agree with Justice Scalia that an expectation for every detail of my life to be private, as a matter of law, is silly. His argument is that blanket privacy laws would interfere with the first amendment. He's right. Privacy can't be handled with catch-all laws. Medical records are, and should be, treated differently than, say, information about my property taxes.

Justice Scalia wasn't too happy about the Fordham professor's assignment but didn't change his position because of it. In a statement to the Above the Law blog, he said:

It is not a rare phenomenon that what is legal may also be quite irresponsible. That appears in the First Amendment context all the time. What can be said often should not be said. Prof. Reidenberg's exercise is an example of perfectly legal, abominably poor judgment. Since he was not teaching a course in judgment, I presume he felt no responsibility to display any.

Actually, on that front, the Justice got it wrong. It wasn't poor judgment; it was a good lesson - a reminder for the Justice and all of us, for that matter, that the information we put on the Internet is definitely accessible by anyone with an Internet connection.

(Image credit: Above the Law)