Tech

The IT behind Alan Shepard's space flight

Alan Shepard became the first U.S. astronaut 50 years ago today. The mission set off a 50-year string leading to companies like Space-X and Virgin Galactic that are aiming to commercialize space. Here's a look at the computers behind NASA in 1961 and what counted as "high-speed" data transmission.

Alan Shepard became the first U.S. astronaut 50 years ago today. The mission set off a 50-year string leading to companies like Space-X and Virgin Galactic that are aiming to commercialize space.

Gallery: America's first small step into space - 50 years ago

Among the notable points from IBM's final report on Project Mercury:

- IBM developed the Mercury Tracking and Ground Instrumentation System.

- The equipping and testing of the system was contacted to the Western Electric Company.

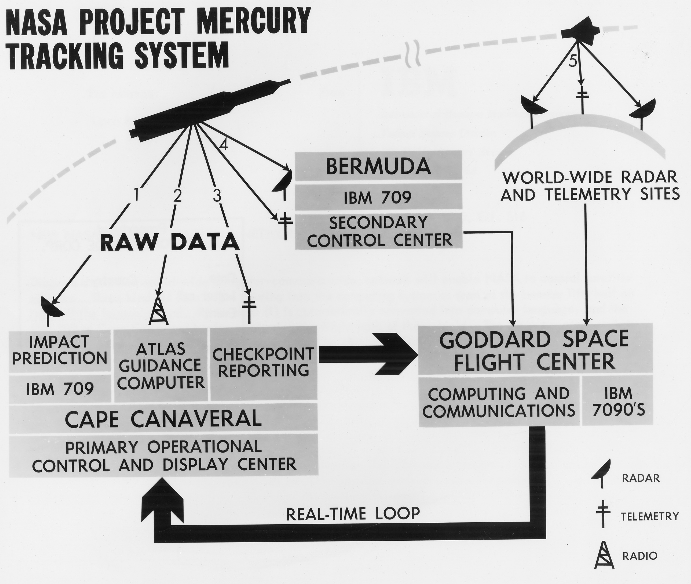

- The ground system consisted of a worldwide network of tracking sites to monitor conditions, a control center at the Goddard Space Flight Center, the Mercury Control Center at Cape Canaveral and another in Bermuda that served as a backup.

- IBM was responsible for processing flight data during orbit and re-entry to supply a real-time record of spacecraft status to mission control.

- Cohen was the designer and number cruncher for the system.

- Big Blue had to install three large computers, two 7090 transistorized ones---which were new at the time---and one vacuum tube 709 computer. The 7090s were "duplexed" for redundancy. After all, NASA wasn't quite sure about these transistorized computers, said Cohen. "Vacuum tubes were seen as more reliable," he said.

- The IBM 7090 computer complex (right) made a go, no-go decision to Mission Control. The 709 in Bermuda also made a recommendation.

- IBM had to design and maintain the launch monitor subsystem.

- The 7090's role was to determine flight trajectory and smooth the position of the spacecraft. It also predicted the future position of the spacecraft.

- The 709 calculated normal orbital flight data and trajectory dynamics.

- High-speed data rates ranged from 7090 messages at a 400 millisecond rate, or about 1,000 bits per second. Those messages contained position and velocity vectors.

Here's a look at the high speed data links:

- All of this data went to a plotboard---a 30 inch by 30 inch dual arm display marked with a 1024 by 1024 grid. Data pairs were converted and applied as a X-Y plot.

See also: