D-Wave demonstrates latest quantum computer prototype at SC07

The words "paradigm shift" don't do justice to the potential of quantum computing. Everyone agrees it's coming, and it's going to turn the industry, if not the entire world, on its ear. Well, it's here now, says D-Wave founder Geordie Rose, who demonstrated his company's latest prototype on the floor of SC07 in Reno, Nevada.

Ok, not actually "on" the floor, because the actual machine is a bit unwieldy at the moment. In fact, it's about as large as D-Wave's entire booth, so demos were run remotely via a web service back to the lab. "We're going to work on making the refrigerator a bit smaller and self-contained," said Rose, thinking ahead to commercial deployments.

The latest iteration of D-Wave's chip has 28 qubits (quantum bits), according to Rose. He said they were on track to show a 512 qubit machine next year, and 1024 the year after that. The die has room for a million qubits. But first things first, says Rose. "If we can't get to 512 qubits by the end of next year, we're in trouble," he admitted.

D-Wave's quantum computer works by seeking the lowest energy state given a set of inputs and constraints. Imagine turning the dial on your FM radio. You go past a strong signal, then reverse the dial and go back and forth until you zero in on the station. Now imagine you have thousands of knobs to turn. That should give you an idea of what goes on in a quantum computer when it's running a program, except that instead of gradually getting stronger or weaker the signal flips between different discrete quantum states. Occasionally the computer might settle on the wrong answer, explains Rose, so they run each program 8 times and take the majority answer. It's weird, but it seems to work.

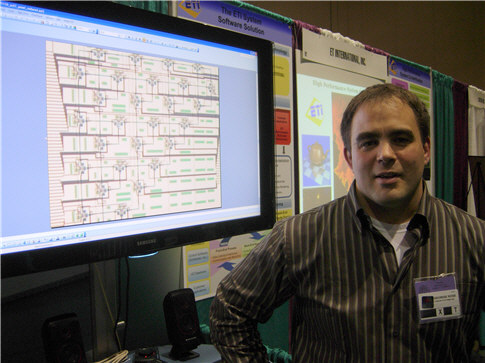

In the picture above you can see a magnified view of the individual qubits on the chip. Each qubit is connected to three of its neighbors. I asked Rose why people were so skeptical of his work. It all comes down to the traditional way of relating discoveries through peer reviewed journals, he explained. They skipped that step, much to the dismay of physicists eager to verify the company's claims. That's going to change, he promised. "We're going to go out to some of the hotbeds of skepticism" in the coming year, he said, with the goal of silencing the nay-sayers. They might even file a paper or two, but it didn't seem to be a priority.

Apparently the US Patent and Trademark office is convinced, having granted the company dozens of patents on the technology. Dozens more are pending. "We have more [quantum computing] patents than any other company in the world," said Rose. Perhaps this is the real plan for the company's future success. Even if the device they've built doesn't prove to be practical, D-Wave (and their investors) should still be able to make a tidy profit from their patent portfolio when somebody really does make a viable quantum computer. "It's hard to imagine anybody building anything remotely like this without running into our patents," Rose asserted.