Generation 'Y do I have to do it like that?'

Working with international company workforces I'm often struck by the sheer diversity of individuals across cultures, age groups and skill sets who are confident in their ability to communicate and collaborate well. There seems to be a personality type that has a huge appetite for learning and using ever more frequent waves of new technology developments that is independent of any particular demographic, and who are eager to participate in group activities online or off.

These folks are often called 'early adopters' and 'techies' in companies and are leveraged in pilot try outs of new technologies.Their opposite I call the Taciturns (habitually reserved and uncommunicative) who have limited interest (or competence and confidence) in collaborating, preferring instead to work solo and communicate on their own terms, and the clash of these two groups has been the demise of many otherwise well equipped online collaboration environments inside companies.

People who are talented communicators have significant advantages in life but also run the risk of not being taken seriously if they don't demonstrate depth of knowledge and a productive work ethic to their colleagues - agile but superficial skaters tend to eventually be shunned by their peers, particularly if they are appropriating and articulating other people's deeper work and ideas.

There's an unfortunate perception sometimes associated with 2.0 technologies that the newest generations of technology are the exclusive provenance of the youngest members of the work force, who will shortly inherit the world and are therefore to be looked up to with their innovative new ways of working.

Some fresh out of school employees have been startled to find that they are looked up to by the people they expected to be learning from in their new job. The surprise is finding themselves perceived by some - and distrusted by others - as being magically endowed with some technological elixir that makes them multitasking information sponges who will have downloaded all the knowledge in the company into their brains in their first week on the job.

This is often unfortunate, particularly for those individuals who had been used up until now to boundaries in life from their educators and family, and who now find themselves being congratulated for the ADD behavior they had been trying to grow out of. I'm exaggerating of course, but I know of at least one instance where this has happened.

The concept of apprenticeships, journeymen and other historical trade rights of passage are currently unfashionable - and virtually unknown - in some circles, with the idea that new employees hitting the ground running in their new jobs, with a flurry of digital engagement, learning and interaction being deemed a desirable trait the old can inherit from the young.

Obviously some of the people who have created the workflows and body of knowledge inside a company through years of service resent the trivialization of their old fashioned ways of working, and some have been led to believe that they need to buck up their ideas and get with it on Twitter, micro/macro blogging, Facebook-in-the-enterprise and other forms of social engagement with their cohorts.

The Taciturns of all ages generally speaking are laughing inwardly at all the teenage leadership stuff they hear being bandied about, and have often already decided they won't be participating in any of that.

Voluble posturing and speculation about millennials, Generation Y, their geo location and socially loosely networked connections, 'the future of work is Facebook' and so on by those trying to decode their cultural petri dish perceptions and futurist crystal ball gazing are in some cases doing a great disservice to many of those entering the workforce.

Most people, even in these economically challenged times, are looking for work where they learn skills and knowledge from their peers, which will make them more valuable as their career progresses regardless of age. People are looking to learn disciplines and ways of working that will get them recognition, kudos and make them more money, while employers are looking for staff who are going to make a meaningful contribution and be competent in the role they were hired into. This isn't rocket science, just common sense.

A huge challenge for modern companies is maintaining organizational cohesion and continuity - and staff loyalty, focus and retention is a large part of that. Loosely coupled networks of individuals can be a powerful corrosive influence outside corporate organizations, whether socializing outside work by disgruntled employees, or the far more sinister realities of fighting amorphous enemies on a military level.

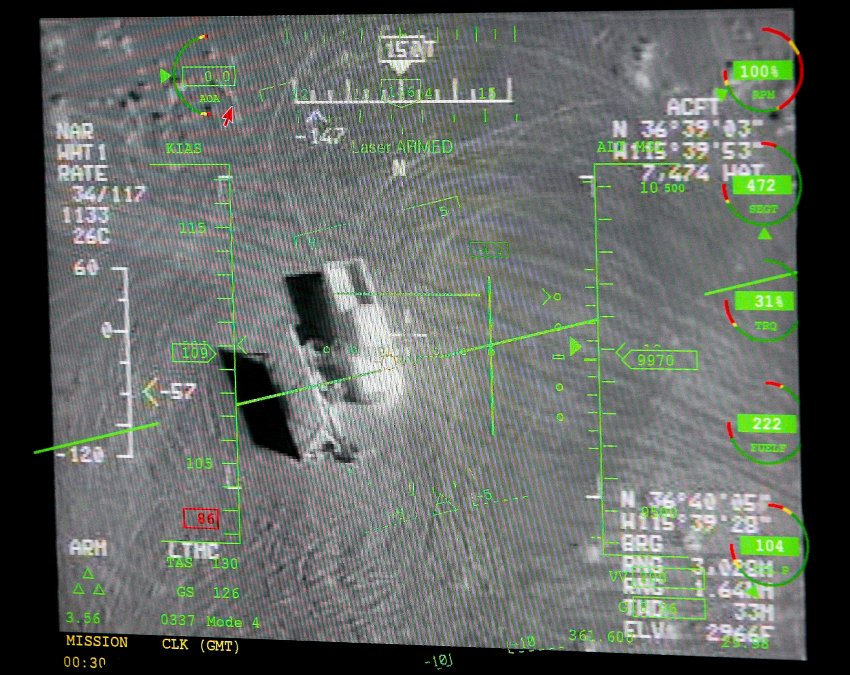

Ex US General Stanley McChrystal's new piece in Foreign Policy magazine ' It Takes a Network - The new frontline of modern warfare' discusses the realities of fighting against a shape shifting, networked enemy whose decentralized choreography is very hard to read

....Decisions were not centralized, but were made quickly and communicated laterally across the organization. Zarqawi's fighters were adapted to the areas they haunted, like Fallujah and Qaim in Iraq's western Anbar province, and yet through modern technology were closely linked to the rest of the province and country. Money, propaganda, and information flowed at alarming rates, allowing for powerful, nimble coordination. We would watch their tactics change (from rocket attacks to suicide bombings, for example) nearly simultaneously in disparate cities. It was a deadly choreography achieved with a constantly changing, often unrecognizable structure. Over time, it became increasingly clear -- often from intercepted communications or the accounts of insurgents we had captured -- that our enemy was a constellation of fighters organized not by rank but on the basis of relationships and acquaintances, reputation and fame. Who became radicalized in the prisons of Egypt? Who trained together in the pre-9/11 camps in Afghanistan? Who is married to whose sister? Who is making a name for himself, and in doing so burnishing the al Qaeda brand?

All this allowed for flexibility and an impressive ability to grow and to sustain losses. The enemy does not convene promotion boards; the network is self-forming. We would watch a young Iraqi set up in a neighborhood and rise swiftly in importance: After achieving some tactical success, he would market himself, make connections, gain followers, and suddenly a new node of the network would be created and absorbed. The network's energy grew.

Corporations are fighting similar commercial battles against disruptive networks of individuals looking for ways to disintermediate and pick off opportunities from successful business entities. With the world's working population aging rapidly, the challenges of transforming large, rigid organizational cultures into more agile and aware networks has never been greater.

The momentum modern technologies enable is taken advantage of relatively easily by distributed smaller networks, as evidenced by the huge Dark Internet, often for short term political or criminal gains detrimental to greater society.

McChrystal:

Our first attempt at a network was to physically create one. We convinced the agencies partnered with the JSOTF (joint special operations task force) to join us in a big tent at one of our bases so that we could share and process the intelligence in one location. Operators and analysts from multiple units and agencies sat side by side as we sought to fuse our intelligence and operations efforts -- and our cultures -- into a unified effort. This may seem obvious, but at the time it wasn't. Too often, intelligence would travel up the chain in organizational silos -- and return too slowly for those in the fight to take critical action.

While many companies with global aspirations have the IT infrastructure and capabilities to 'meet in a big tent to share and process intelligence' some are still chasing red herrings around generation gaps and attempting to hang planning off limited life social marketing ideas, failing to see the greater strategic and tactical values and perils in attempts at deploying modern social software...