Engaging Citizens the Right Way: Government Uses Twitter During Hurricane Irene

A note on this post: This post was written by Bob Greenberg, President of GHInternational, a noted expert on emergency response management and particularly the way that we can use contemporary means to get citizens engaged and organized in intelligence and rescue efforts. He is also my brother and someone who I trust with my life.

That said, I also have an abiding interest in how we can get citizens to collaborate in providing on the ground information that no device can get; how these same citizens can get involved in the efforts to save lives and how this can impact our world in ways that we can imagine but barely fathom for its importance.

During Hurricane Irene, my brother told me of some of the work, he, others and some governmental agencies did to use social channels to organizes efforts. It blew me away. I asked him to write this post and he did. And I hope it blows you away too. Because if it does, it might save some lives someday. Read this one.

Take it away bro'

For the last several years there has been a lot of discussion about the use of web based social media for the engagement of citizens. Nowhere has this discussion been more active and persistent, nor more important, than in what I will call broadly the emergency preparedness and response (EPR) community.

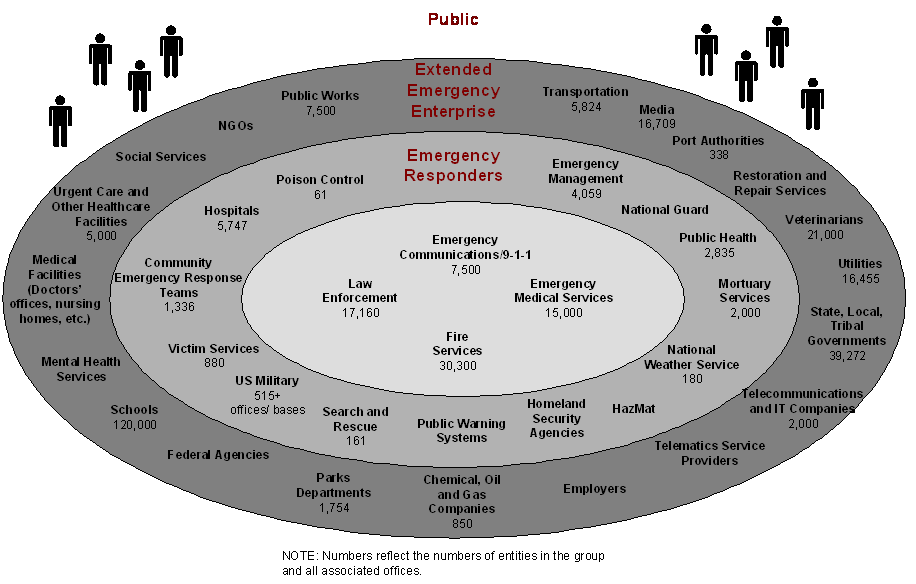

The reason can be summed up in the words of FEMA's Administrator Craig Fugate who has repeated stated that effective emergency preparedness and response has to take a "whole of community" approach where participation in community discussions and establishing mechanisms for online engagement are critical. Not only is it often the case that the "first responder" in an emergency is your neighbor, but everyone affected by a crisis is involved in one way or another. The following graphic provides an understanding of why this is the case.

One of the most important elements of that discussion has been trying to figure out how to "cut through the noise" and sift through volumes of information now available via social media channels before, during and after a crisis. With the widespread use of social media there is a virtual "fire hose" of information coming at people from all directions at once. (John Battelle raised this in a more general way on his blog, "Twitter and the Ultimate Algorithm: Signal over Noise (With Major Business Model Implications)."

The majority of organizations simply don't have the means to process such large amounts of data, not to mention analyze it. The problem becomes even more difficult in a crisis when emergency preparedness and response (EPR) organizations are relying on this same information to make life saving decisions. How do you decide what data is even trustworthy, not to mention important for making informed decisions quickly?

While the discussion on the best means to do this existed prior to the February 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the response to that event by hundreds, if not thousands of technology savvy volunteers and the widespread use of mobile technologies by Haitian citizens and responders on the ground kicked the issue into high gear. A summary of these efforts was included in a report issued by the United Nation's Office of Coordination of Human Affairs (OCHA) with support from the United Nations and Vodafone Foundation was released early this year titled "Disaster Relief 2.0.: the Future of Information Sharing in Humanitarian Emergencies"

There are numerous issues yet to be addressed (as identified in Disaster Relief Report) but one thing that has become crystal clear is that the use of social media is a critical part of improving citizen engagement before, during, and after a crisis. For example, government agencies (at all levels) have started to recognize the importance of communicating to the public through social media; many states now have Twitter and/or Facebook profiles in addition to the thousands of sites set up by local government. On the federal level, Craig Fugate, the Administrator of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is actively involved in discussions on the usefulness of social media for disaster response, and uses Twitter and Facebook regularly as part of his information toolkit.

Now to Irene

The use of social media in preparation for and during the response to Hurricane Irene gives us the first glimpse of the direction this is taking as well as the challenges that are still remaining as it gave us three "firsts."

- Irene demonstrated the first widespread use of social media during an emergency in the United States by the public and by official response agencies. To paraphrase my colleague Jonathan Fisk - social media became part of the permanent infrastructure for use in EMR activities. This is not surprising as a recent survey by the American Red Cross titled, "More Americans Using Social Media and Technology in Emergencies" found, for example, that "followed by television and local radio, the Internet is the third most popular way people get emergency information." This was demonstrated during Irene in spades which saw over 3,000 tweets per second being generated.

- Irene was the first event where use of social media was used by a large number of government agencies in preparation for and during the actual event. FEMA, for example, explicitly directed people in the path of Irene to authoritative websites, social media sites such as Twitter and Facebook, and mobile apps and streamed messages through various social media sites and Twitter hashtags including #FEMA and #CraigatFEMA. New York City, led by the City's Chief Digital Officer Rachel Sterne, did the same directing people to either www.NYC.gov or, when that went down, instructed the public to follow the hashtag, #NYCMayorsOffice (an interesting commentary on this can be found at http://codeforamerica.org/2011/08/29/technology-in-a-hurricane/ ). In an interview on CNN, FEMA Administrator Fugate identified that the use of social media, along with television and radio, may be more useful than cell phones at times, as cellular communication infrastructure is often overloaded and unreliable during a crisis. My colleagues who were working with various agencies in preparation for the storm were able to identify over 250 official government Twitter feeds that were regularly used to send information to the general public (@saraestescohen/east-coast-response-orgs). We were also able to identify another 100 feeds being used by Not for Profits (NFP) and the media.

- Finally, it was the first time that the broader response community - that is non- government (which could include not for profits and the private sector) were able to have their social media efforts begin to be integrated into the official preparedness and response efforts. The Red Cross for example had trained digital volunteers monitoring and providing updates on Irene via a variety of social media channels. And, according to an article in New Public Health titled, "Red Cross Gets Twitter Badges for Hurricane Irene" these volunteers were given digital verification badges from Twitter "to help reassure the public that these updates were coming from a reliable source."

Filtering the Noise: The Emergency Management Twitter Map

While these developments are important and encouraging, the issue of "cutting through the noise" stands out as one that has to be urgently tackled.My company, GH International, working with the Department of Homeland Security's First Responder Technologies Program and Florida's Division of Emergency Management, took an initial step toward addressing how to better organize social media (within an existing operational context) in preparation for Irene.

As mentioned above, the G&H team identified over 350 Twitter feeds from government, NFPs, and the local media that provided an enormous amount of timely information about Irene. We manually vetted each source to verify that it was from an official response organization, a recognized NFP, or a media outlet (by looking at the profile and contact information, followers, and previous tweets). At the request of the government officials we were working with, we did not include information from non- authenticated public sources. The challenge was that it was difficult to filter the feeds without monitoring hashtags. Even using aggregation sites like Tweetdeck didn't help because there were simply too many feeds to follow.

The solution we developed (in partnership with the Florida Division of Emergency Management) was to create an Irene Twitter web service that aggregated the official local, state, federal, NGO and private sector Twitter accounts into a dynamic data layer that enabled officials from every state on the Eastern Seaboard of the U.S. to view, sort, search and analyze the information from within their native geospatial mapping environment (i.e. Google Earth, ESRI's ArcGIS, etc).

FDEM published the Irene Twitter web service we created on GATOR, a state geospatial platform that was developed for use during emergency response and that was tracking developments relating to Irene. We alerted over 6,000 officials to its existence and from there it was picked up by many more.

Because FDEM had this information published on their website, any interested parties (public or official) were be able to access those geographically referenced Twitter feeds that were relevant to them with other information displayed in a relational context. So, for example an official - or citizen- in the Outer Banks in North Carolina who wanted to see what was going on with the storm's predicted path, storm surge zones, evacuation routes, traffic flow, and shelter status in contiguous communities could also simply search and discover relevant Twitter feeds on GATOR. This would help them cut through the noise of all the other feeds and get them only that information that was relevant to them at that time, significantly improving their situational awareness.

While there are many other excellent examples of the use of social media during Irene, the differentiator was that the Irene Twitter web service we deployed enabled people/operators/responders to integrate the official Twitter feeds as a data layer into their native operational environment. They did not have view these feeds using a separate website, another map, or to use an unfamiliar tool. The task that remains are to assess just how effective and useful these tools were and what could be done to improve them. We are already working on various ways to improve the filtering capability of the EM Twitter Map web service and I'm certain others are working on improvements as well.

Another innovative social media effort organized by the mapping software and data company, Esri focused on developing a map that aggregated feeds from Twitter, YouTube and Flickr. To view the latest hurricane news on this map, it is available on their website.

There is a virtual "industry" that has emerged that is discussing and beginning to identify best practices of the use of social media for citizen engagement with government during a crisis - and by extension in day-to-day activities. Organizations and discussion groups such as the Red Cross , the #SMEM community (#SMEM and #SMEMCHAT on twitter) , the Department of Homeland Security's Virtual Social Media Working Group , the International Network of Crisis Mappers, Crisis Commons, Ushahidi, and others are addressing these issues on a daily basis and have held a number of meetings to address these issues including one held by the Red Cross in August 2010 (http://bit.ly/aQEtmG and a meeting sponsored by #SMEM at the National Emergency Managers Association in March 2011 (http://crisiscommons.org/2011/09/03/smempape). And they are interacting with federal, state and local government officials to look for the best ways to integrate their efforts most effectively.

This is just the beginning. As I write this numerous people are working on improving these capabilities with an eye to further empowering and engaging citizens and creating a deeper level of collaboration with government. Moreover working these issues in the emergency management domain is really a "use case" for all of government. It's just a matter of applying the same approaches to other issues. That is something I think we can all look forward to.