Researchers to mimic marine animal camo in high-tech materials

The Office of Naval Research has awarded a $6 million grant to researchers to emulate the extraordinary ability of some marine animals to instantly change their skin color and pattern to blend into their environment.

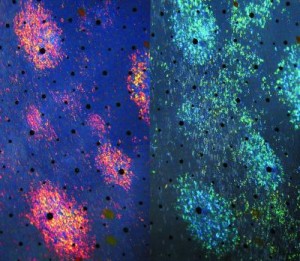

The highly angle dependent iridophores - reflective pigment-containing cells - in a squid. This image shows the same iridophore splotches viewed at normal (red) and oblique (blue) viewing angles.

Camouflage expert Roger Hanlon of the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) and award co-recipient Naomi Halas, an expert in nano-optics at Rice University, are collaborating with materials scientists and nano-technologists towards the goal of developing materials that can mimic cephalopod camouflage.

Cephalopods are a class of invertebrate animals with huge eyes that include cuttlefish, octopuses, and squid. Several species can seemingly vanish into their surroundings making them the unrivaled masters of dynamic camouflage.

Over the course of his 30 years of research, Dr. Hanlon has been observing how this "smart skin" works allowing cuttlefish, for instance, to disguise themselves at night and even deceive other cuttlefish.

“This project will enable us to explore an exciting new avenue of vision research – distributed light sensing throughout the skin,” Hanlon said. “How and where that visual information is used by the nervous system is likely to uncover some novel neural circuitry.”

In 2008, Hanlon and his team discovered that cephalopod skin contains opsins, the same type of light-sensing proteins that function in the eyes. As part of the funded research, they'll perform experiments with cephalopods to determine how opsin molecules receive light and aid the animal’s visual system in adjusting skin patterns for communication and camouflage.

Dr. Halas said in a news release: "Our deliverable is knowledge, the basic discoveries that will allow us to make materials that are observant, adaptive, and responsive to their environment.”

It will be interesting to see if the research will unlock the camouflage mechanisms of these marine animals and then how it could eventually translate into applications for the military.

Related:

Acoustic cloak hides underwater objects from sonar

Fly corneas prove viable for biomimetic surfaces, i.e. solar cells