Amazon Kindle DX: The solution to a problem that doesn't exist

Oh, and less page-turning, naturally.

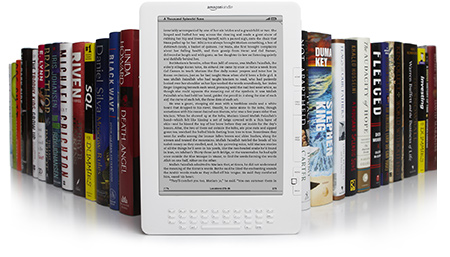

For the most part, I like the design of the Kindle DX, whose lines it shares with its smaller sibling, the Kindle 2. The sloping corners and wide buttons are made for hands, briefcases and purses. The e-ink, by its very nature, is relaxing to your eyes and versatile in different lighting. The device is thin and light, but not flimsy. Really, the only detail complicating the device's form is the gaggle of Casio calculator watch-style buttons at the bottom.

Amazon must truly be given credit for the Kindle family, its first foray into hardware: after all, how do you reinvent the book -- a format that has been perfected over thousands of years?

But a book isn't Amazon's declared aim with the Kindle DX, though those with poor eyesight may prefer it over the smaller six-inch Kindle model. Instead of books, Amazon would like to bring you more content to read: newspapers, magazines, textbooks. The company's "Kindle Vision" is to bring you content to read in 60 seconds. The DX is an extension of that goal, but it doesn't take a radically different path.

Practicality: A solution for business or pleasure?

That's a great thing for business-minded people, who can now take PDF office reports with them to read on trains, flights and other transport. No more lugging around 100-page reports; no more burning-lap, strained-eyes syndrome from trying to read said report on your 13-in. laptop.

The debate, however, is if that's a great thing for consumers who aim to use the Kindle DX as a leisure device. At $489, the new Kindle DX is in no way inexpensive, living up to the "DX" ("deluxe") name well.

For rabid readers, it's a no-brainer: at $10-$15 for a new paperback, the Kindle DX breaks even at roughly the 45th paper book purchased.

But for those who spend a month or more with a book, the Kindle DX is doubtlessly a luxury item: you are paying dearly for the convenience of a one-stop shop for reading.

The math gets even more complicated when you take the Kindle DX's intended formats -- newspapers, textbooks, magazines and reports -- into consideration.

[Image Gallery: Hands-on with the Amazon Kindle DX]

All the news that's fit to download

Some of the first rumblings about the new Kindle DX is that it could give newspapers their (staid, color-in-the-lines) personalities back. At the Kindle DX launch event, Amazon announced partnerships with the New York Times, Boston Globe (owned by NYT) and the Washington Post. Without revealing pricing, the company said subscribers of these newspapers would receive discounted Kindle DX devices.While it's nice to see the Times, Globe and Post in their native format, it isn't quite a deal for the consumer, whatever the price. The majority of the content these news organizations offer is news, followed by analysis and commentary. But the advent of the Internet has made news a nearly-free commodity, and in fact neither the Times, Globe or Post charge for their content. These papers are banking that you'll pay them to appreciate the original layout of their content. I doubt many people will.

At the press conference, New York Times Co. chairman Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. made it a point to highlight "those who do not currently receive home delivery of the Times" as prospective customers. The fundamental problem with this concept is that nearly everyone receives home delivery of the Times now, thanks to the cable plugged into the back of their computer.

Cracking college textbooks -- and wallets

The theory of the Kinde DX for students is a nice one: no more lugging around textbooks, saving paper, saving money, and being technologically hip.

The reality, however, is that the Kindle DX is simply far too expensive a proposal for a student -- be it one at $60,000/year Harvard or the $3,000/year local community college. There is a reasonable, albeit slightly apples-to-oranges, argument for the iPod touch with consideration to an inexpensive media browser. But the iPod touch isn't built for extended reading and annotating, rendering the argument slightly moot.

Really, the main problems for student adoption of the Kindle DX aren't competitors -- they are the price tag and professors.

Books at college can run up to $400 per semester. The Kindle DX is intended to last longer than that, of course, but this is under the assumption that the student won't break or damage the device quickly and all a prospective student's material is available through Amazon's service.

At this point in time, that's simply not the case.

Many professors, in addition to using standard curricular texts from major publishers, choose smaller books -- sometimes self-authored -- they deem relevant to the course as reading materials. Few of those, by definition, are available via Amazon.

The upswing to this is that "coursepacks," or cheaply-bound paper collections of readings and excerpts compiled by the instructor, have become a popular campus choice in place of true, bound textbooks. The Kindle DX's native PDF support certainly makes it technically possible to read coursepacks on the Kindle, but the student is dependent on the professor to have the technical know-how, and the will, to do so.

That's a tough proposition.

[Video: Amazon Kindle DX in action]

First-bound fumble: magazines & reports

And finally, what of magazines?

Simply, the Kindle DX is far from being an optimal format for a magazine. Not only does the Kindle DX's monochrome screen sap all the life away from the art department of every publication, but it also removes the "two-page" magazine feel: A picture or design element that spans two pages, which is presented more often than you think in glossies. By only viewing a magazine one page at a time, you're reading a stunted publication -- even if the PDF support makes it easy to get a magazine on the device in the first place.

Further, there's still an element to paper that can't be reproduced by the Kindle. To be frank, would you take an issue of Sports Illustrated to the bathroom with you? Would you take a Kindle DX?

Display limitations also apply to reports and other office documents, particularly the lack of color. Graphs, images -- and in the case of textbooks, diagrams -- are all stuck in 16 shades of gray. For mathematics and langugage material, that's not a problem. For a color-coded anatomic illustration of the major systems of the human body, that's an issue.

...But would you buy it?

In a vacuum, that's a lot of green: things you could buy for that price include two iPod touches, one or two Blu-ray players, an Asus Eee PC 1000HE netbook, a Sony Alpha A200 digital SLR camera, two or three semesters' worth of books (at a very liberal 50% buyback price), two Boston-to-Washington round-trip fares on the high-speed Acela train, or enough magazine and newspaper subscriptions to fill your mailbox three times over.

And that's before you pay for any of the content.

This wouldn't be such a hard pill to swallow if the content wasn't marginalized like it is. But the New York Times or Newsweek or Janson's History of Art simply aren't the same on the Kindle DX, even if they can fit. The lack of color only magnifies the problem.

That's not to say Amazon's at fault here. The Kindle DX makes a lot of sense in the short timeline marking the evolution of e-readers, and the device will probably make a tidy bundle by targeting relatively affluent customers.

But it simply isn't quite there as a substitute for the real thing. Is anyone complaining about how hard it is to get the news? Or how heavy a newspaper is? Is anyone complaining about anything but the price of textbooks?

And are you willing to drop $500 for a proprietary solution to eye strain from reading reports on the plane? (Perhaps you are.)

Kindle DX: Solution in theory, not in practice

The Kindle DX, I fear, is an answer to a problem that doesn't exist. It's a necessary step toward an eventual portable content solution, and a good improvement on the paperback-sized Kindle 2. So much so, in fact, that I believe the DX will usurp a not-insignificant portion of the sales of the original Kindle.But it in no way makes me any more likely to ditch my habitual reading of NYTimes.com each morning, or my subscription to GQ, or the occasional newsstand purchase I may make. And as a student, I simply couldn't see fronting that kind of cash for a device whose features significantly overlap with a required laptop, which allows me to read my course readings and news and write a paper about it.

Is the Kindle DX important? Yes. I believe it will help the Kindle family become even more popular, make Amazon more money and further e-reader development. But make no mistake: it remains a niche luxury item until the price is brought down to $150 or so.

It's hard not to like the Kindle, mainly because it aims to revolutionize a task anyone reading this article is fond of: reading. But until Amazon reproduces that experience in a more complete fashion and makes reading as inexpensive a habit as it currently is, it will remain out of reach for most consumers and out of touch with most publishers.