Consumers as producers: Disintermediation without a net

Most of you know that I've been tracking closely the inversion of control seemingly being ushered in en masse by the Web. That the interesting parts of the Web are increasingly contributed by its users directly, or indirectly, apparently establishing that the sheer mass of innovation is in control of the greater Web community rather than by a few centrally controlled outlets. The implications for business seems to be that control over a lot of things is moving from top-down to bottom-up, or at least heading in one particular direction instead of the other. (Witness the music industry's seemingly slow slide to near-oblivion wrought largely by this.)

But nothing beats dry prognostication about trends on the Web better than an interesting story about it. I've been tracking Jeff Jarvis' (in)famous Dell Hell story for a while now but his latest post yesterday on the subject of conversations between companies and their customers is not-to-be-missed and uncovers plenty of relevant thinking on this topic.

Ostensibly, it's an argument between PR maven Amanda Chapel and Jeff Jarvis about whether companies, particularly large ones, will ever really have to listen to their customers at an individual level (says Jarvis, "Now, when you deal with one customer, you deal with all customers.") Of course, the premise of blogs, wikis, and all the social networks springing up underfoot these days, is that individual people do seem to matter more, particularly when they can freely communicate, collaborate, and share information. It's been an enormously successful model in some ways and has in its own right birthed a number of large multi-billion dollar companies.

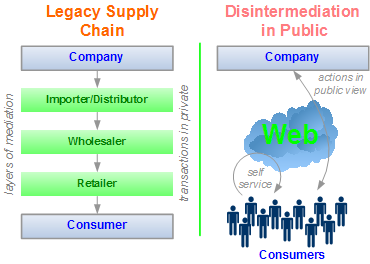

If true, this obviously has potentially significant implications to most companys' relationships with their customers since they can no longer treat individual customers shabbily without fear of the negative feedback being posted somewhere on the Web and being used against them. Jeff calls this the "real public relations" these days. It's disintermediation in public, without a net.

However, Amanda disagrees entirely with this premise, saying:

In business, "control" is a fiduciary responsibility. Stock is property. Management is paid to increase the value of shareholder property AND to act as custodians. It is a "duty." Simple as this: this whole "ceding control" and "open borders" mentality, at the very least, threatens shareholder property. Hype aside, the downsides of your revolution are fairly predictable and surely greater than the yet-to-be-measured upsides. Imagine shareholder activist(s) sharing the podium fully with the CEO. That’s just plain silly. It will happen the same day the CEO decides to blog the annual meeting. NEVER!

In the end, Amanda then pulls the unfortunate communism card, essentially saying that the Web is an little more than an unruly mob intent on looting Corporate America and will never get the respect or attention it deserves because that community just doesn't possess enough credible value or real control.

In this way, if you ever needed a warm-up conversation to prepare you for some of the arguments you'll encounter trying to explain the importance of Web 2.0 in the enterprise, this is a wonderful microcosm. Indeed, I have similar discussions all the time as people try to ascertain whether the Web and blogosphere has the same democratizing effect in reality that it seems to have to those that spend far too much time elsewhere. Indeed, I sometimes even agree as my recent concerns around political efforts to use the Web as a grassroots organizing tool. They might have a significant upside in terms of things like fund-raising but might have little practical outcome in actual elections (in that support doesn't equal votes.)

Does Web 2.0 in fact have sustained relevancy beyond a devoted and insular, albeit large and growing, online audience?

To help answer that, I can only point to examples of self-organizing online communities effecting measurable results to everyday people that really does seem to matter. Katrinalist is still my favorite example of this. Jimmy Wales' new Campaigns Wikia is another one to watch. And one of the more interesting human interest Web 2.0 sites I've come across lately is Matching Donors, a site where people can locate needed transplant organs by connecting directly with those that are donating them. And there are many others, maybe even a long tail of them.

And this points to the second trend in disintermediation in public, that people are increasingly conducting business amongst themselves, without even much of an enterprise in the way.

Back to the argument at hand however. Who is right? Even though many corporations seem less than eager to have real, close-up conversations with their customers, Jarvis is correct in that those that have the hard numbers to prove show that it's worth it, even necessary, to engage in. And not having conversations with your customer doesn't mean that they won't be doing it anyway. It's increasingly clear that you can't even opt out.

Like Starwood Resorts recently said, people don't want to hear the corporation's message about how great their properties are, instead "the most important thing for travelers is word of mouth ... other people's experiences." Are examples like Starwood merely ahead of the curve, or in a unique industry that doesn't apply to anyone else? Unfortunately, that's what most of us would like to know. This highlights again the discussion about conversation that we came in with. Says Jarvis, one last time:

And that is the real branding. Your brand is your reputation, your trust, your value. You don’t own your brand; your customers do.

Is your company trying to make heads or tails of the use of blogs for customer communication? Go on, tell us your story.