FCC hearings: Comcast versus Vuze

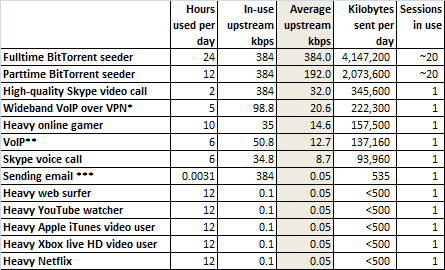

The FCC held its hearing on Comcast's Network Management practices at Harvard University yesterday. Vuze executive Gilles BianRosa whose company filed one of the two FCC complaints against Comcast reportedly told the FCC yesterday that BitTorrent does not hog bandwidth. Since most Internet experts would dispute that claim, I generated the following hard data on the bandwidth consumption of various applications that run on the Internet.

Note: Richard Bennett who was an expert panelist at yesterday's hearings informed me that BianRosa claimed that BitTorrent didn't exceed the contracted limit. That however ignores the explicit "no server" clause in the terms of service and no broadband service was built to be fully saturated 24x7. This is why commercial grade T1 lines that offer less than half the speed of broadband connections costing 8 times less are $400 per month.

Bear in mind that the data below is in reference to upstream (upload) bandwidth consumption in kilobits per second since that is the focus of these FCC hearings. Also note that applications like web surfing hardly use the upstream at all since it's primarily your clicks and URLs that are being transmitted to tell the web server where you want to go.

* Corporate VPN telecommuter worker using G.722 codec @ 64 Kbps payload and 33.8 Kbps packetization overhead ** Vonage or Lingo SIP-based VoIP service with G.726 codec @ 32 Kbps payload and 18.8 Kbps packetization overhead *** I calculated that I Sent 29976 kilobytes of mail over the last 56 days averaging 0.04956 Kbps

It is interesting to note that before the advent of P2P applications, Broadband users were primarily downloaders and rarely did they ever upload. It is for this reason that Broadband networks were built asymmetrically and heavily favored the downstream. Servers in data centers with commercial-grade Internet connections served and transmitted content and consumers consumed that content by downloading them.

If you're downloading video from a service like Apple iTunes, Microsoft Xbox Live Marketplace, Netflix, or YouTube, you're only downloading and not uploading anything. Those services pay a lot of money for their own datacenters filled with servers, their own bandwidth, and/or they pay services like Akamai to cache and distribute their content over the entire Internet.

Vuze on the other hand uses a different business model where they don't pay for their own bandwidth and they expect their users to contribute their upload bandwidth to make the service work using the BitTorrent protocol. Vuze basically gets free distribution because they enlist their own customers to be their servers and bandwidth providers using their own computers and broadband connections. So instead of paying for commercial distribution, Vuze offloads their bandwidth on to the broadband providers.

<Next page - Exacerbating the Cable and Wireless spectrum scarcity>

Disclosure: Many people have asked me for the source of the data so I will put out the following disclaimer. As I already indicated in the first paragraph of this article, I am the original source of those charts and graphs. I’ve written extensively on VoIP bandwidth consumption as the former Technical Director of TechRepublic. Before TechRepublic, I built and designed networks for a living. I worked on the routing, the switching, and the traffic engineering of Intranet and Internet based networks. The in-use bitrates I cited are detailed and include packetization overhead and they can be independently verified.

Exacerbating the Cable and Wireless spectrum scarcity

For a DSL network or a fiber network such as Verizon FiOS, handling the massive upstream traffic is challenging but nowhere near the kind of challenge facing shared-medium technologies like Cable and Wireless broadband providers. Every DSL or FiOS customer has a dedicated connection to their broadband provider. While DSL and FiOS providers can't guarantee the 384 kbps to 5 Mbps upstream they advertise for every customer, congestion problems can be dealt with at the gateway terminating the broadband connections. But no matter how much congestion there is, the dedicated copper or fiber connections going to every home will remain perfectly healthy. If the backhaul becomes too saturated on a frequent basis, the broadband provider can upgrade the fiber optic transceivers (not the fiber cabling) for the backhaul or at worst they have to replace the router on each end.For Cable broadband networks which operate on a shared medium (much like Wireless broadband), that much upstream traffic results in packet collisions and a network meltdown if nothing is done to curb the excessive users. Congestion problems are far worse in a shared medium because the problems can't easily be solved by normal traffic shaping like they can on a DSL or FiOS network and more exotic measures need to be taken.

Cable broadband providers can move up to DOCSIS 3.0 like Comcast's new "Blast" service which increases the upstream capacity 12-fold but BitTorrent and other P2P applications can fill all of the additional capacity. While the level of congestion would be far better than a DOCSIS 1.1 network that Comcast currently uses for most of their networks, it doesn't negate the need to manage the network and control excessive uploaders. Wireless broadband providers are even more limited in what they can do because there is only so much the scarce unlicensed spectrum can do. The licensed spectrum isn't as congested but it's extremely expensive and scarce.

Note: While TV broadcasters no longer have to carry analog TV after February 19th 2009, Cable providers must continue broadcasting analog TV beyond that date and using up valuable cable spectrum.

| Upstream | Downstream | # of BitTorrent 24x7 seeders to kill network | |

| Cable DOCSIS 1.1 | 10 Mbps | 40 Mbps | Less than 26 (1) |

| Cable DOCSIS 3.0 | 120 Mbps | 160 Mbps | Less than 60 (2) |

| Wireless 802.11g ISP | 16 to 20 Mbps shared between up and down under good conditions | Less than 10 (3) | |

- Fewer than 26 fulltime BitTorrent seeders saturating their upstream at 384 kbps 24x7 kills a DOCSIS 1.1 network

- Fewer than 60 fulltime BitTorrent seeders saturating their upstream at 2 Mbps 24x7 kills a DOCSIS 3.0 network

- Fewer than 10 fulltime BitTorrent seeders OR uploaders/downloaders can kill a Wireless 802.11g ISP. This is because a Wireless LAN is not only shared, but it's shared between upload and download.

Dealing with BitTorrent in a shared Cable or Wireless broadband network is critical to the health of the network. These networks simply do not have sufficient upstream capacity to be used as a commercial-grade Internet connection meant to serve content to the rest of the Internet. This is why Cable and Wireless Broadband providers all have explicit terms of service that tell the customer "no servers" or nonstop hogging of the resources that affect other customers.

Had Comcast put a ban on 3rd party VoIP providers in their terms of service, then that would clearly be an example of an arbitrary block designed for the sole purpose of being anticompetitive. The FCC has shown that they will shut down such anticompetitive behavior in the past with the Madison River Communications case where VoIP provider Vonage was blocked. But Comcast's terms of service weren't arbitrarily placed there for anti-competitive reasons; they were placed there because of the fundamental limitations of the network. They policy was specifically targeted at the heaviest bandwidth users only under heavy network duress for minimal impact and maximum fairness to all of the users.

Note: The Free Press likes to complain that certain Comcast users (AP reporters) who were trying to seed small files like the King James Bible were blocked from sending those files to other Comcast users. Free Press argues that these couldn't possibly be bandwidth hogs because the files were small and the clients were few. But this is a highly unrealistic and contrived argument because BitTorrent doesn't work very well when there are few users who want a file. Fewer users means the pool of uploaders are few and they may not stick around to keep the Torrent alive.

The other serious flaw with this argument is that Comcast offers a generous amount of personal webhosting space at no extra charge. Comcast customer Richard Bennett actually took his personal Comcast web space and put up that same copy of the King James Bible that the AP reporter was trying to send. Bennett also confirms that he has very few problems seeding this file on his Comcast connection. By hosting the file on a web server, no scarce upstream bandwidth is used on the Cable DOCSIS network.

When anyone tries to download this file from Richard Bennett's Comcast web space, it is capable of delivering the file at more than 3000 Kbps. If I try to download it via BitTorrent from Bennett's computer, it would only deliver 384 Kbps at best and tie up Bennett's computer and Broadband connection. The moral of the story is that a low-bandwidth BitTorrent Seeder simply doesn't exist because there are far better ways of distributing low-bandwidth files.

When a company like Vuze switches to the P2P model where they want to offload their bandwidth and server costs to the Broadband network and home computers, something breaks. But Comcast isn't singling out BitTorrent or Vuze and targeting a specific protocol because they're permitting BitTorrent downloads and uploads without any sort of throttling. Comcast doesn't even ban BitTorrent seeders and permit them to go unobstructed most of the day while network conditions permit. The only thing Comcast does do is block seeding when traffic congestion gets really bad. That means Vuze or other BitTorrent-based companies still get to freeload off the Comcast network most of the day to deliver content to Comcast and the rest of the Internet, but they don't get to do it at the expense of the vast majority of Comcast customers at the busiest times of the day.

While we might debate whether Comcast's terms of service constitutes adequate disclosure, it is critical that the FCC declares Comcast's specific targeting of bandwidth hogs only at crucial times of the day as "reasonable network management". While it's always popular to slap down a large corporation like Comcast, banning this sort of network management will have grave consequences on the Cable and Wireless broadband industry as a whole. It will have a chilling effect on small independent wireless operators like Brett Glass and harm the very competition our Nation seeks to foster.

Disclosure: Many people have asked me for the source of the data so I will put out the following disclaimer. As I already indicated in the first paragraph of this article, I am the original source of those charts and graphs. I’ve written extensively on VoIP bandwidth consumption as the former Technical Director of TechRepublic. Before TechRepublic, I built and designed networks for a living. I worked on the routing, the switching, and the traffic engineering of Intranet and Internet based networks. The in-use bitrates I cited are detailed and include packetization overhead and they can be independently verified.