Cyber-retaliation: How security is becoming a priority for the Middle East

Kevin Mitnick was in town recently For anyone who doesn't know the name, in the mid-1990s, Mitnick was the most-wanted and best-known hacker in the world.

Back in 1995, it was not just the world's computer press that covered his story. The daily newspapers realised they had a new antihero to tear into, warning the public of the dire threats we faced of a hacking epidemic. Thanks to Mitnick and his prison sentence, hacking exploded into the conscience of the general public.

Now a world-famous former hacker and renowned security expert, he flew in to Dubai to speak at the Gulf Information Security Expo & Conference. Although hacking is infrequently reported in the Middle East, IT security is big business, with all the major software houses having offices in the region. Instances of cyberattacks are on the rise, becoming more sophisticated and, in some cases, having political ramifications seen around the world.

Mitnick's timing was perfect of course, because two days before his arrival, the Virgin Radio website in Dubai was hacked, in protest at the growing international celebrity culture of the UAE. Although Arabic music in the UAE is popular, with so many expats living in the country Abu Dhabi and Dubai have become mainstay slots in bands' international tours, with artists such as the Stone Roses, Metallica, Bruno Mars, Guns n' Roses and Kanye West having played here so far this year.

According to UAE newspaper The National, the Emirati hacker, calling himself OxAlien, was angry at the number of western bands playing — usually to packed crowds — in the UAE. He left a message on Virgin's site claiming: "Your database is with me. I'll sell the admin login script in the black market to get some cash. No files have been deleted from your server."

Mitnick's message to delegates at the conference was that hackers are increasingly using social engineering techniques to find and then attack weaknesses in companies' security — a technique he mastered as a teenager. Describing it as a low-risk, cheap and high-return method of attack, he told the audience that no software security can protect against such methods, because social engineers exploit human nature.

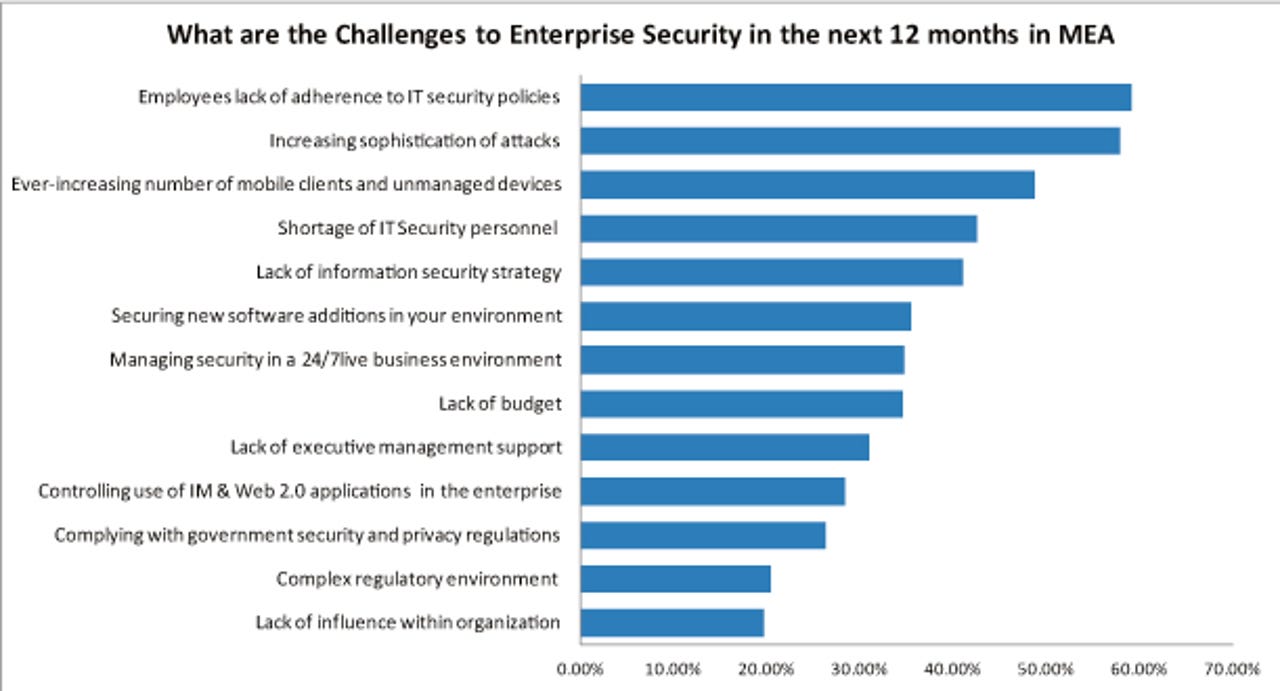

In April, the analyst group IDC reported that in the Middle East, a lack of adherence to IT security policies by employees was the number one challenge faced by IT professionals, followed by the threat of increasingly sophisticated attacks. The analysts said that with the combined growth of mobile devices used in the workplace that require securing, the increasing sophistication of threats and the (albeit it slow when compared to Europe and the US) growth of cloud services, organisations in the region are beginning to change their security strategy, turning to managed security services.

The amount of money spent on IT security is growing at 15 percent a year, IDC said, and in some cases, companies are spending big to protect their networks. Last year, MEED reported that the major national oil companies in the Middle East spend around $10m annually to secure their systems.

Security is high on the minds of IT professionals in the region and attitudes are hardening. When I first got to the Middle East, I never got the feeling that external attacks were considered a major threat to businesses based here in the same way that it is in other regions.

Hacking of the sort suffered by Virgin Radio may be unusual here, but is not unique. In mid-May, Saudi Arabia admitted that some of its government websites had come under a sustained denial of service attack, with a group called Saudi Anonymous using Twitter to not just claim responsibility but also provide a running commentary of its actions and targets in both Arabic and English, finally declaring on 18 May that: "Today is our last day on #OpSaudi, moi.gov.sa [Ministry of Interior] will be our last target."

The group used the hastag OpSaudi as it updated on the attacks. It put out the cryptic message #OPpetrol, with a message on 13 June saying simply "1 week". If an attack had been slated to start on 20 June, the world's hydrocarbons companies would have had plenty of warning to prepare.

But while the attacks on Virgin Radio and Saudi government sites are a malicious inconvenience, the big threat now is around the major industries of the Middle East. This was brought home a couple of years ago, when the IT systems in Iran's two nuclear power plants were attacked.

The Bushehr nuclear facility, central to the worldwide sanctions that have been imposed on Iran, was hit by Stuxnet. Discovered in June 2010, the malware was designed to attack control systems and in particular Siemens' program logic controllers used in industrial facilities to manage parts such as control pumps and pressure gauges. Once Stuxnet was introduced to Iran's nuclear power plants, it is believed by USB in 2009, it allowed the attacker to sabotage the control systems.

The attack, blamed on the US and Israel, damaged both Iran's centrifuges and its nuclear ambitions, delaying the opening of the plant. But it also brought home to organisations in the Middle East that cyberattacks were a real threat, it highlighted the importance of strong security systems and caused some internal soul searching. If Iran's nuclear facilities can be hit, then could the same happen to the region's oil and gas facilities, so important to the economies of the oil-exporting nations, or the power and water desalination plants?

And of course it did. In August 2012, the national oil and gas company of Saudi Arabia, Saudi Aramco, was hit. One of the world's most valuable companies, at an estimated $10 trillion, and the world's biggest oil producer, pumping about 12.5 million barrels a day from its fields, Aramco was hit by a malware attack that infected 30,000 computers. This was swiftly followed by a similar attack on RasGas in Qatar.

Like Aramco, RasGas, which is 70 percent owned by government entity Qatar Petroleum, said that its operations were not impacted by the attack. But as the world's second largest producer of liquefied natural gas, at about 36 million tonnes a year, any impact on its production would have hurt countries around the globe. Its exports go to South Korea, India, Belgium, and Holland, among others. The UK is also reliant on RasGas, with tankers delivering LNG to its three main gasification terminals of South Hook, Dragon and Isle of Grain. Iran was blamed in both cases, although there has been no official confirmation that its government was behind the attacks.

Now, security experts elsewhere are warning that the instances of attacks emanating from the Middle East is rising fast, with around 10 US utility companies the target of attempts to take over plant processes (sound familiar?). So far, no group or country has been blamed but the US Department of Homeland Security has put companies on alert. And it is difficult not to allow the thought to float across your mind that this just might be a dangerous game of cyber retaliation.