If vendors cannot keep a phone updated, why trust them with your household items?

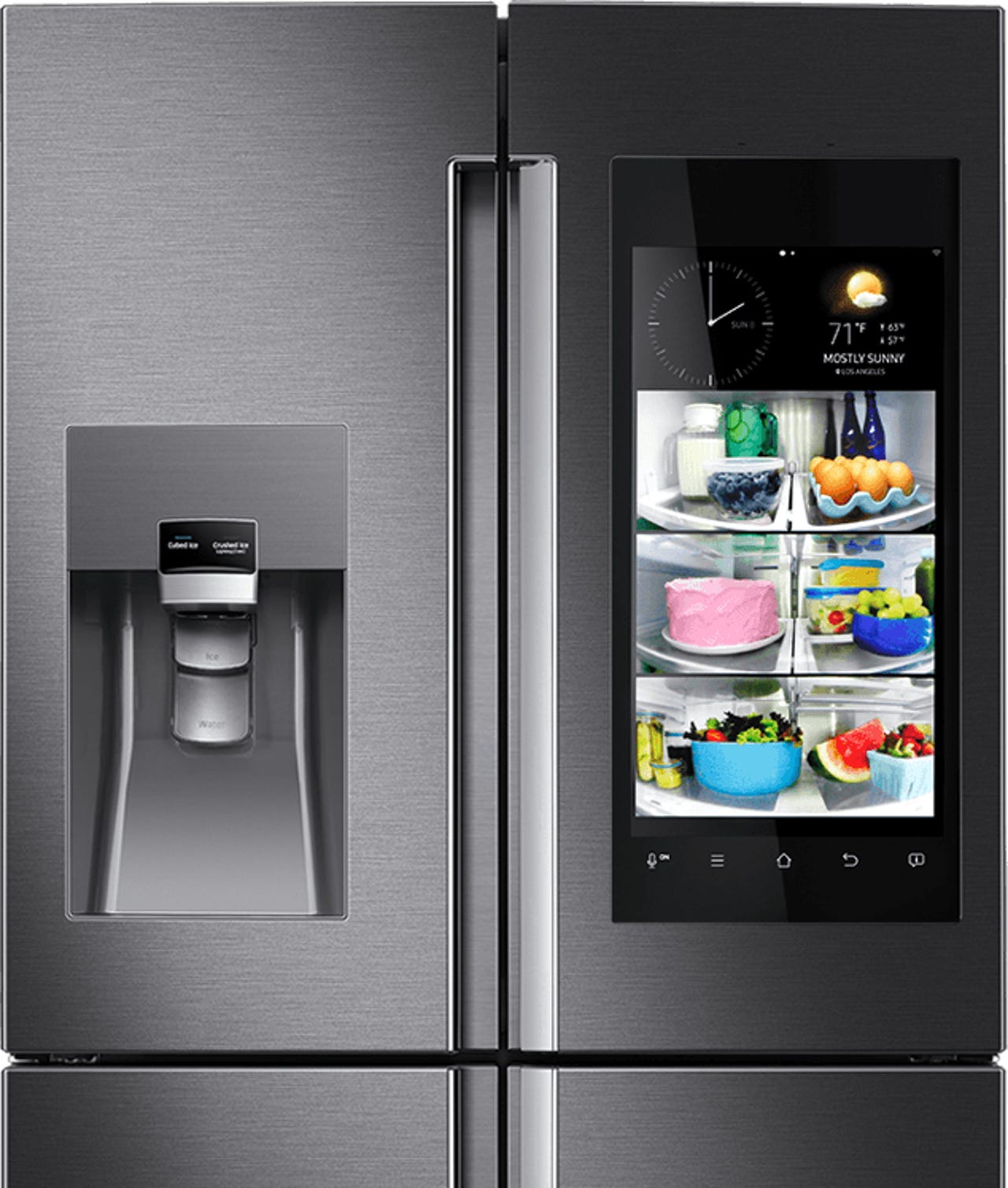

A household applicance or a long-lasting automated DDoS machine that happens to cool your drinks?

As an everyday consumer, when you approach the cash register for a new piece of electronics, the cashier will typically ask if you want to purchase the extended warranty.

It's an interesting transaction, one where a consumer parts with money now, so that in the future they may have to dig through receipts from years ago and navigate the loops and doublespeak the vendor has put in place to avoid coughing up for a replacement. In this scenario, the purchaser is usually at fault or operated the device beyond the tolerances in the fine print.

But in the very near future, there is one aspect the makers of household goods will need to address, and that is information security.

As consumer goods makers rush headlong to embrace the world of smart devices and internet of things, they are treating their products as set-and-forget devices.

If you were offered a Wi-Fi saturating, internet-available, zero-security telnet server in your loungeroom that also doubled as a baby monitor, you wouldn't go for it -- but that is exactly what consumers are doing.

Shocking few observers, the usual suspects at CES 2017 once again continued to bang small amounts of computing power into home appliances and other products.

To pick on two conglomerates that happen to make both mobile devices and whitegoods, if you have been the owner of a Samsung or LG smartphone in recent years, chances are you received Android updates for a bit over a year, and, if you were really lucky, maybe two years.

Now take that same operating model and apply it to the realm of household goods where the lifespan is many multiples more than your average phone lifespan, or, if you prefer, consider the security situation if your fridge was running on the operating systems available at the turn of the century.

Things start to get pretty grim if you consider the number of times an internet-connected board running Windows 98 would have been owned in the last 16 years if it was left to rot on the line.

This concept isn't new -- those who talk of impending Refrigergeddon are approaching Cassandra-like levels of unactioned forewarning.

Unlike physical warranties, it's hard to argue that a user mistreated the software or made it perform beyond its limits. Given the vast majority of users will have no idea what software their devices are running, responsibility for looking after the security of these smart devices will rest with the vendor, or nobody.

The problem with leaving smart device updates in the hands of nobody is that it now allows denial-of-service attacks that impact large parts of the internet.

A rare ray of light appeared in 2017, with the United States Federal Trade Commission deciding to go after D-Link for putting its customers at risk of unauthorised access by failing to secure its IP cameras and routers.

Hauling vendors in front of the courts may have to occur more often if the visions of a more connected world come to pass and security remains an afterthought. Particularly if the defence taken by D-Link seems to be: No one was breached, so everything is fine.

In Australia, consumers have a number of guarantees that come automatically upon purchase, including that the products be of acceptable quality, safe, lasting with no faults, and fit for purpose.

The time limits on such guarantees are not prescriptive, though, and instead fall under the banner of "reasonable" expectations, which can be quite subjective.

However, the average consumer is likely to expect a household appliance such as a fridge to work in a reasonable manner for more than five years, and if you are maintaining the software for such a device, that means you need to be able to push patches and upgrades, and plug security holes as they appear -- especially for bundled libraries, such as OpenSSL.

The end game should be vendors choosing software that can be looked after in the long term, rather than slapping a pretty user interface that accords to this season's fashions and be tossed aside within a year -- but this is a fairytale unlikely to happen any time soon.

Until such a nirvana is reached, the dumbest appliance is likely to be the most future-proof appliance.

ZDNet Monday Morning Opener

The Monday Morning Opener is our opening salvo for the week in tech. Since we run a global site, this editorial publishes on Monday at 8am AEST in Sydney, Australia, which is 6pm Eastern Time on Sunday in the US. It is written by a member of ZDNet's global editorial board, which is comprised of our lead editors across Asia, Australia, Europe, and the US.

Previously on Monday Morning Opener:

- Apple's iPhone turns 10: Here's how the device impacted business, work

- The 4 tech trends that will shape 2017

- The 5 biggest tech trends of 2016: ZDNet editors sound off

- The biggest threat to artificial intelligence: Human stupidity

- Cloud compute pricing bakeoff: Google vs. AWS vs. Microsoft Azure

- Can Trump stop the automation revolution and save US jobs?

- The PC is having its mid-life crisis, just a little bit early

- Apple to revive the Macbook, as iPad falters and IBM launches biggest Mac rollout ever