India's electronics manufacturing still a dream

When India came up with its National Electronics Policy a few years ago, it seemed like a revolutionary and very necessary idea. The policy's aims: Reduce the $100 billion consumption of electronics goods in India that will swell to $400 billion by 2020; find employment for some percentage of the 12 million college graduates that are entering the workforce every year and desperately need jobs; and boost the fortunes of the manufacturing industry — the one major Achilles' heel in the Indian economy — and, by doing so, add to the country's GDP in a vital way.

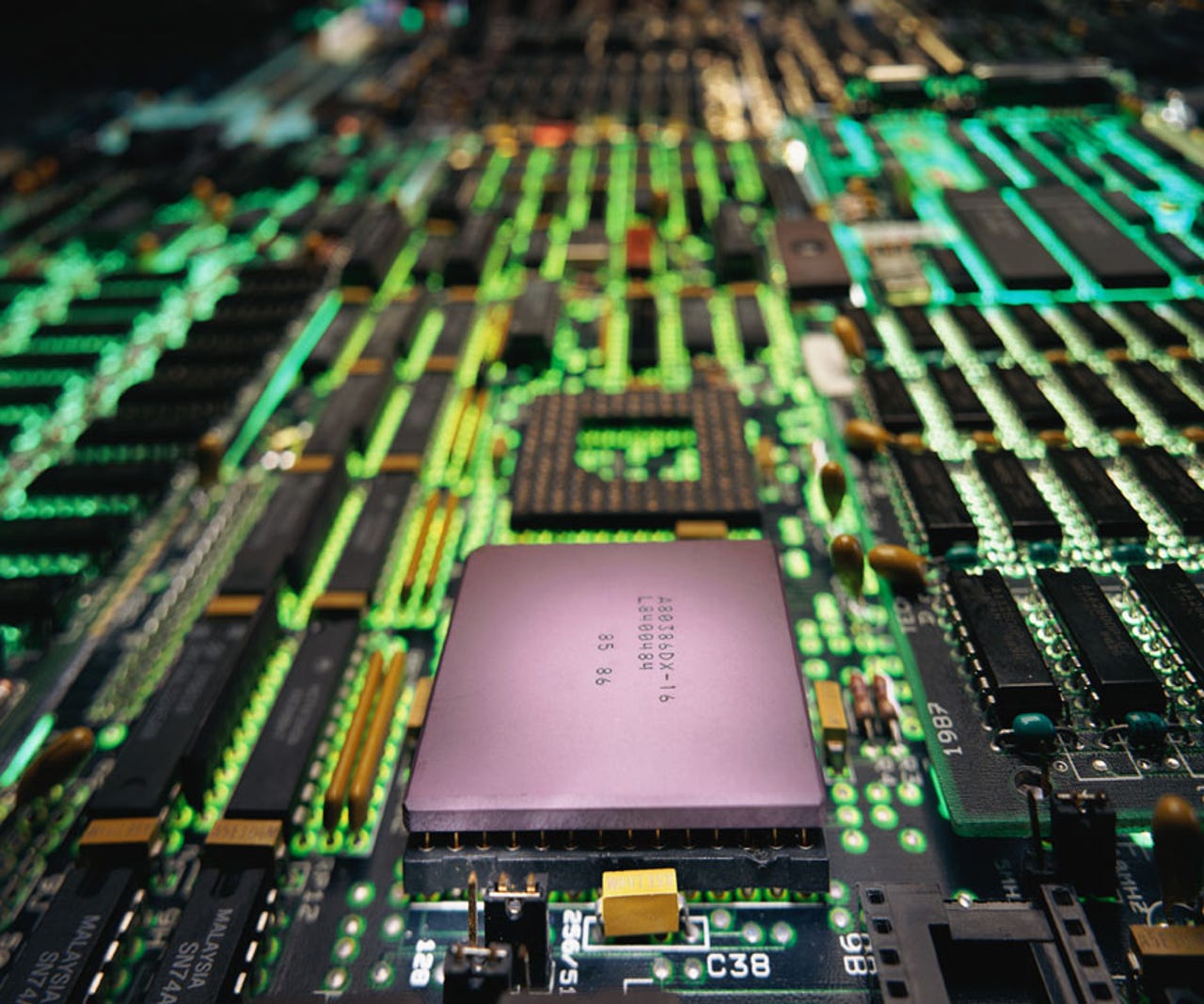

All of this would be done by the government's issuance of capital equipment subsidies and other fiscal incentives across the electronics value chain. The idea was to help facilitate the emergence of electronic clusters like those in Taiwan or Japan. The weapon of choice would be a Modified Special Incentive Package Scheme (M-SIPS), and aiding the whole process along was the grand plan of setting up one if not two semi-conductor wafer fabrication plants. Reviving its nearly dead domestic electronics and hardware sector was a national priority, considering how alarmed people were about the possibility of Chinese spyware being embedded in their phones, telecom equipment, or even hardware procured by the military.

However, these grand plans still remain a pipe dream. To be sure, the Indian Cabinet finally approved setting up two fabrication plants earlier this year. One is a joint venture between India's Jaiprakash Associates, TowerJazz, and IBM, located in New Delhi with a price tag of Rs 34,399 crores ($8.5 billion). Another one is planned for Gujarat, and is to be built by a consortium fielding India's HSMC Technologies, Malaysia's Silterra, and Europe’s STMicroelectronics. But, so far, all of these are just agreements on paper.

Featured

What we do know, however, is that so far, no large-scale manufacturers of electronics have moved to India, including home-grown phone companies such as Karbonn and Micromax, which say that doing so is not even a remotely realistic idea, according to this Economic Times article.

The reason seems fairly logical: "Nothing is yet available to us here. In China, while designing a phone, for each component, we can choose from several options. The cells, cameras, plastic, and the metallic body, to name a few," said a senior smartphone company executive. (One reason cited is because the government releases a quarter of its subsidy contribution two years after the company invests its own cash.) Since it doesn't look like many investors have taken the bait, the minimum investment limit that was once an optimistic Rs 100 crore ($16 million) is going to be slashed to Rs 10 crore ($1.6 million).

Recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi also announced a "Make in India" blueprint that aspires to bolster this previously conceived plan by promising to eliminate red tape. The government website "Invest India" is a pretty slick affair, unveiled with great fanfare and with the aim of guiding investors through the process of clearances and picking joint venture partners. Priority sectors have been identified, and a torrent of information is available.

Yet, slick marketing and information alone will not a manufacturing powerhouse make. A company still has to somehow get those clearances, and without major land, labour, and administrative reforms, as this Quartz article points out, it will be pretty much left spinning its wheels in the mud, like before.

Clearly, India's potential hangs in front of it like a tantalising but so far unreachable fruit — after all, it has had great success in the embedded space, churning out smart devices such as controllers. It also has some of the best fab design outfits in the world, and most foreign fabless companies, such as Freescale, have captive R&D units here. It has talented engineers and an ability to orchestrate projects at stunningly low costs. So, becoming an electronics powerhouse — or at least a contender — is not an altogether delusional goal.

The question is, can it get there soon enough at the pace with which it is tackling its ills? With wages in China going up and around 100 million workers up for grabs in 10 years because of this trend, India has a golden opportunity to absorb some of this capacity. But it will have to get serious about making its country manufacturing friendly — which also includes an infrastructure overhaul and a successful push to skill the hundreds of millions of youth — in order to take advantage of this trend.

The percentage of India's population in manufacturing is currently 15 percent, but it needs to boost that figure to 25 percent if it has any hopes of staving off economic and social upheaval. And that will require an effort that may be far beyond what the country is currently primed for.