Intel Light Peak: a tech guide

USB 3.0, with headline throughput of 5Gbps, has only just hit the market, but it could be obsolete as soon as next year, when Intel's 10Gbps Light Peak optical cables arrive. In time, a whole new protocol will deliver up to 100Gbps, but initially Light Peak will plug into familiar ports to deliver faster transfers over longer cables.

Copper can't keep up with the bandwidth that peripherals require, says Jason Ziller, director of Intel's optical I/O programme. Achieving the 5Gbps throughput of SuperSpeed USB (USB 3.0) took significant changes to the standard and could be the limit: "They had to redo the signalling, they had to add new wires, they had to shorten cable lengths from five metres to three metres. Electrical speeds and capabilities are hitting their limits. There's a general acknowledgement the next speed bump needs to be optical". PCI and Ethernet face the same problem, as do graphics connectors.

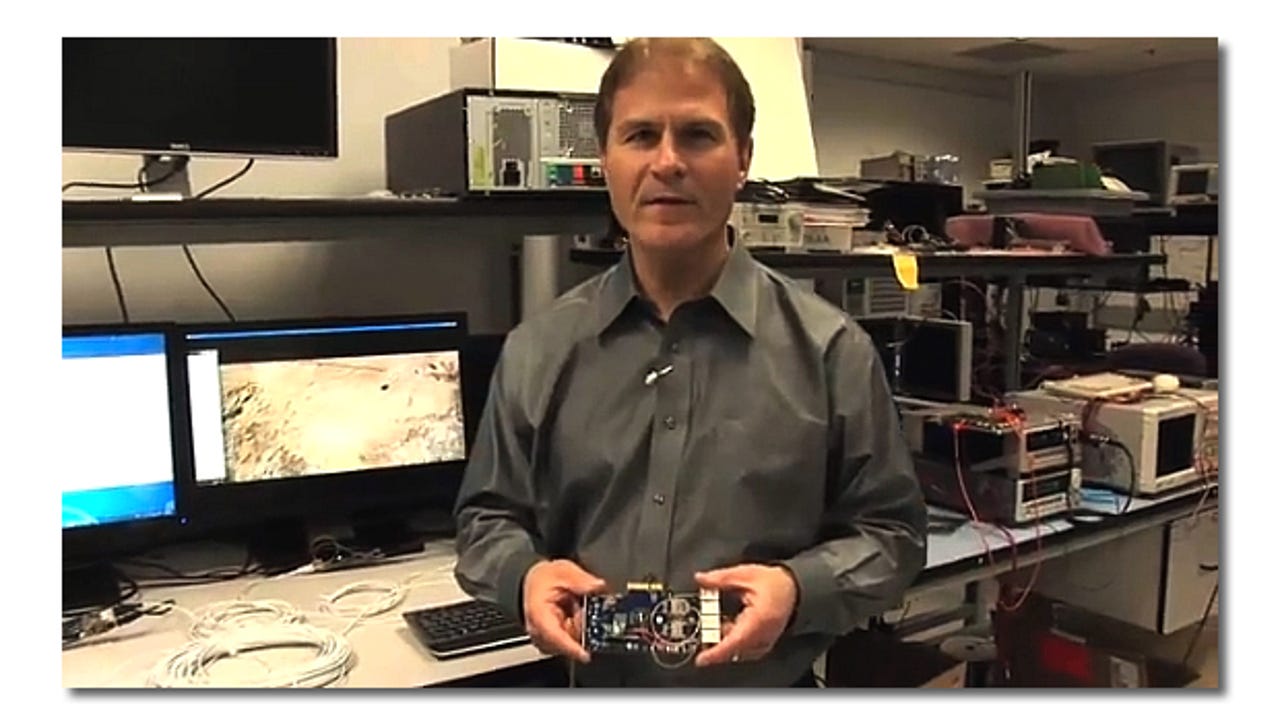

Jason Ziller, director of Intel's optical I/O programme, shows off Light Peak technology at Intel Labs

Light Peak cables can be very thin and flexible — and longer than copper. "If you want longer HDMI or DisplayPort cables," says Ziller, "you need extenders, you need adapters and the cables get thicker… it's not so much 'can you do it?' but 'how much will it cost and how inflexible will the cable be?'."

Light Peak will use familiar connections like HDMI or the USB plug (and protocol) — they'll just be faster, and they may use less power. At 10Gbps you can copy a Blu-ray disc in less than 30 seconds, and that's just the start: "We can do multiple lanes, like PCI Express, and run two lanes with four fibres and get 20Gbps. We can go up to 100Gbs over the next decade", claims Ziller.

Achieving compatibility will limit cable length, and for USB 3.0 that could be 3 - 4.5 metres. With a future Light Peak protocol, cables could be as long as 100m (some consumer electronics companies are considering it for home wiring). Unlike USB, Light Peak daisychains devices, so you could interconnect your home entertainment system and connect on to your PC too.

Light Peak's common optical I/O architecture for a mix of ports, protocols and connections is cheaper to build into a PC — or a docking station — than multiple controllers. "In the short term," suggests Ziller, "the biggest use will be putting this into a docking station so you get all your display connections, Ethernet and storage through a single cable going into your laptop."

Won't break, won't break the bank

Up to now, optical connectors have been too expensive — and too fragile — for general use. Light Peak will "radically reduce the cost from the way optical devices are made today," according to Victor Krutul, Light Peak senior manager at Intel, who predicts that Light Peak cables will be no more expensive than HDMI.

Intel's Light Peak add-in card comprises a protocol-handling controller and a module that converts signals between electrical and optical

At the heart of Light Peak is an Intel-designed controller chip that handles the protocols, along with an optical module that converts electrical signals to photons and vice versa — the add-in board shown above replaces a previous, much larger and more complex, controller. Having two optical fibres (one to transmit, one to receive) rather than decoding two-directional traffic reduces the complexity (and hence cost). Ultra-hard telecoms-grade lenses bend the light 90 degrees (from incident to planar light) to take it from the cable to the controller, but these are 25c injection-moulded Ultem plastic rather than glass. Using standard components — like low-power, low-cost Vertical Cavity Surface Emitting Lasers (VCSELs) already made for datacentres — keeps down the price. A Light Peak module is now straightforward enough to be assembled on a production line in four seconds.

A prototype Light Peak cable (left): it has the familiar USB connector, but under the pre-stretched Kevlar are two optical fibres. The large connector (right) is the kind of optical transceiver installed by specialists today and is a single channel, 10Gbps connection. The connector on the twin LightPeak fibres beside it is one eightieth of the size and handles two channels.

Light Peak cables will have to stand up to daily use and abuse. "Today, optical systems are installed and maintained by professionals," says Krutul; "everyday users will be plugging and unplugging cables all the time, dropping it in the sand, getting jelly in the connectors…" Light Peak will be rated for 7,000 insertions, which matches or exceeds other PC connections.

The plastic lens is recessed by 1mm from the end of the cable, so you're less likely to touch it. Even so, the Light Peak team tested the effect of dirt on the connection. "We did take suntan lotion and actually paint it on there," says Krutul. "We took a magic marker and literally painted onto the edge of the lens and plugged it in and it worked. We had a fingerprint test where we touched the end of the plug 5,000 times. We bought mill-grade dust and circulated it in a dust chamber for two hours, at 11 or 12 miles per hour. When we opened up the door, the boards and connectors were literally just covered in dust. And after that we had .1dB, .2dB loss, which is very small."

The internal diameter of each LightPeak fibre is 62.5 microns (around half the size of a human hair, but thicker than the fibre used in telecoms). The beam expander moulded into the lens expands that to 700 microns, so that dust — usually around 100 microns — may interrupt the beam partially but the connection will still work. The beam expander also compensates for distortion or movement in the connector after you've been using it for a while. This thicker fibre means it doesn't have to be aligned as accurately, Krutul explains: "If you're 4 microns off in the alignment of an 8-micron fibre you've lost half your light; if you're 4 microns off on 62.5 microns you've only lost five or six percent".

Glass fibre has tensile strength greater than steel, but at 62.5 microns thick it's fragile. USB cables are often rolled up, and that can crack the glass fibre. Light Peak fibre has a 3-micron coating to prevent cracking — you can bend it to a radius of 3mm and it won't break, says Krutul: "We've tied the cables in multiple knots to make sure it didn't break and the loss is acceptable — usually about .1dB to .2dB. We have on the order of an extra 5dB of margin to compensate for things like that", he says. To stop the fibre breaking if you pull on it — if an external drive slips off the edge of the table, or you just yank the cable out of the socket — the cable includes pre-stretched Kevlar (as well as a copper wire for power). "You can almost get two people pulling on it at once and it won't break the fibre", says Krutul.

When will devices have Light Peak?

In January, Intel CEO Paul Otellini promised: "You can expect PCs to have this in a year from now". The components of Light Peak are finished and working, says Jason Ziller, but third-party component manufacturers have to start manufacturing them and PC makers have to design them into systems: "We're looking to go to market with the components later this year, and we expect systems to be available on the market early next year", he says. The PCI card that Intel has used to demonstrate Light Peak with USB connectors isn't a product yet, but if there's demand to upgrade existing PCs it could come to market.

Intel is talking to manufacturers of consumer electronics, PCs, peripherals and phones about a Light Peak standard that will take advantage of 'the full capability' of fibre, although this could take 'a few years' to finalise. The official process starts later this year, and there are early adopters: "Sony and Nokia would like to work with us on a global standard for mobile computers and smartphones", Ziller confirms. Toshiba is positive about Light Peak too: "I think it could supersede USB 3.0 very quickly", notebook product manager Ken Chan told ZDNet UK. However, Light Peak will take longer to appear in phones, warns Intel's Ziller: "the solution we have today wouldn't fit into a phone, but we're on the path to miniaturise in next few years".

The switch to optical won't happen overnight, so you'll still be using copper cables for the foreseeable future. But it will happen, says Ziller: "the move to optical connections is a transition to a whole new generation, and we need to start it now".