Kepler finds first 'habitable' planet orbiting distant star

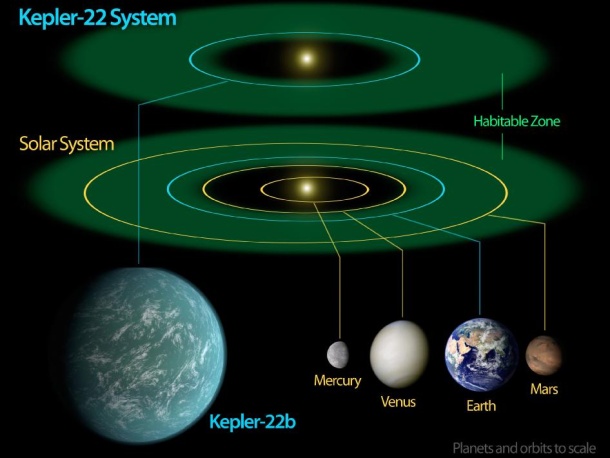

It's 600 light years away, twice the size of Earth and has the unassuming name of Kepler-22b. But Nasa says that the planet is the first we've found, apart from our own, that could have liquid water on its surface — in other words, it orbits its star in a habitable zone.

Found by the Kepler project using the Spitzer orbiting telescope in conjunction with ground-based observations, Kepler-22b still has many mysteries. We don't know whether it's rocky like Earth, gaseous like Jupiter or Saturn, or even mostly liquid, but we do know it's the first of more than a thousand candidate exoplanets — those orbiting other stars — that passes the first test for life support.

Others have come close: two other small planets orbiting stars cooler and smaller than our sun have been discovered, right on the edge of their systems' habitable zones, rather like Mars and Venus are on the edge of ours. But Kepler-22b's sun is G-type, very similar to our own Sol if slightly smaller and cooler, and the planetary orbital period is 290 days, again in line with our own.

"Fortune smiled upon us with the detection of this planet," said team leader William Borucki, Kepler principal investigator at NASA Ames Research Center in California, in a news release. "The first transit was captured just three days after we declared the spacecraft operationally ready. We witnessed the defining third transit over the 2010 holiday season."

After some debate, the Kepler team's first definition of a habitable zone was adjusted and tightened up after the first list of 54 possibles was reported as part of a major project update in February 2011. However, longer observation periods have increased the number of potential Earth-sized planets known by more than 200 percent since then, raising expectations that many more will be categorised as potentially life-supporting.

"The tremendous growth in the number of Earth-size candidates tells us that we're honing in on the planets Kepler was designed to detect: those that are not only Earth-size, but also are potentially habitable," said Natalie Batalha, deputy science team leader at San Jose State University, in the release. "The more data we collect, the keener our eye for finding the smallest planets out at longer orbital periods."