Meet Android's patron saint: The IBM PC

Ice Cream Sandwich is here, a new version of Android soaking its way towards us through the lumpy sponge of the operators.

There is, as usual, a flurry of articles about Android fragmentation: by some counts, there are over a thousand different variations of hardware and software out there marching under the robot flag. How can any developer cope? How miserable must the punters be, in such chaos?

Even discounting Android's most vile public crime — that it offended Steve Jobs and is therefore haraam — there is an inescapable trade-off at work. A tightly controlled platform is easier to get on with, as a user, developer or manufacturer. It also offers more potential for controlling supply and access, which encourages high margins and market distortion.

An open platform encourages competition and differentiation. But as diversity goes up, the chances diminish of any particular variation being the best, however you choose to define it — so most are sub-optimal. And developers have to decide how much of that market to approach — not the hardest part of the job, but one much easier when there's less choice. As the Dead Kennedys so cogently observed: give me convenience or give me death.

Your iPhone is either the best iPhone or nearly the best. Your Android almost certainly isn't the best Android. That's inescapable logic, but says little about what that choice actually means — nor what it's actually like to use an Android phone.

The question isn't even about which of the Apple or the Android approach is better, whatever that means. The market is improved by having both: it's better to have two dogs fighting each other than one dog growling at you. Rather, are the downsides to Android's openness so bad as to make it unsustainable? Is variation venomous?

A lesson from history

We've been here before, in the early days of another transformative technology. Thirty years ago, a tiny company called Microsoft created an operating system called MS-DOS, the defining feature of which was that it ran on the Intel 8086 chip. The rest of the hardware, it didn't really care about: manufacturers could configure MS-DOS to run on their particular systems, and many did.

Trouble was, MS-DOS wasn't much of an operating system, and developers (programmers, as they were called back then) soon found it easier and more effective to bypass it and control the hardware directly. The result was messy: you could buy an 'MS-DOS compatible' PC and find a lot of 'PC compatible' software wouldn't run properly. There was pain, and lots of it.

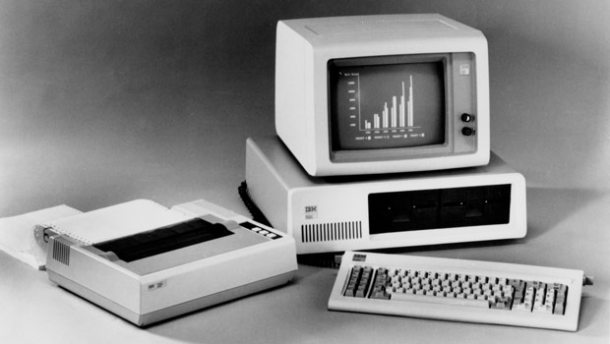

Can Android learn lessons from the IBM PC? Image credit: IBM

Inadvertently, IBM saved the day. It had commissioned MS-DOS to go with its own 8086-based PC, the hardware design of which was basic but flexible. Developers wrote for that hardware platform first; other PC manufacturers found that if they made certain key parts of their products compatible with the way IBM did things, they also got the best software first.

The effect on the market was to produce an open yet standard hardware platform, driving down prices, encouraging differentiation in ways that didn't break compatibility and creating a lot of choice. The process was so successful that in time, even Apple adopted the resulting hardware — and IBM got out of the PC business altogether.

The Android you're looking for?

Is that possible for Android? Not only possible, but inevitable. With every force on the planet driving mobile technology down in cost and up in number, there are ever fewer choices for the hardware designer, combined with increased pressure to create standard parts with standard interfaces. (That's one reason among many that Intel hasn't got a prayer in handsets: the ecosystem is maturing fast without it. It has as much chance there as the PowerPC had on the desktop.)

The result will be that the major points of incompatibility will be sorted out over time and subsumed into the standard Android experience, with plenty of room for icing on the top.

Yes, you'll always be able to buy an Android device that runs out of upgrade before the one your annoying friend bought instead. But no, that won't kill the platform. It won't alter the fact that, for most people, the best phone is the one that's with you and that, for most people, the hardware upgrade cycle will be so close to the operating system's cadence that the difference is otiose.

Fragmentation is another word for diversity, and diversity is another word for evolutionary potential. Provided only that Android is flexible enough to develop freely in a changing world, its future is guaranteed in a way that other systems, defined by a central intelligence, are not.

Get the latest technology news and analysis, blogs and reviews delivered directly to your inbox with ZDNet UK's newsletters.