Ancient vulnerabilities are geddon in the way of security

"We are failing at communicating to the rest of the world," says James Lyne, global head of security research at Sophos. "I think that we have a fundamental broken behaviour in this industry that we need to go and shift." And he's got numbers to back up his claim.

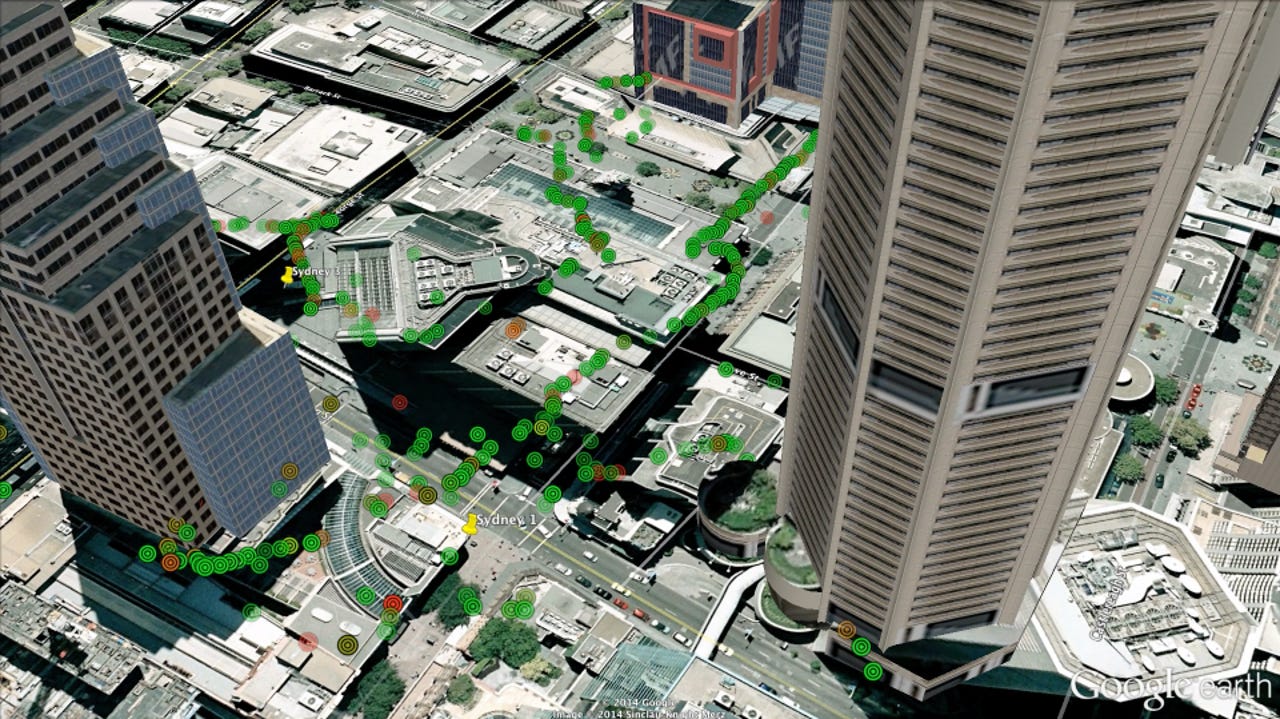

Lyne has been warbiking. That's exactly the same thing as wardriving, that is, driving around a city to map out its open and poorly secured wireless networks, but with more lycra. His results for London and San Fransisco are already online, and those for Las Vegas, Hanoi and Sydney are coming soon.

On Wednesday, journalists were given a preview of Sydney's results, which Lyne described as the "least worst of a bad bunch".

Of the 34,476 wi-fi networks he detected while cycling Sydney streets, 1,371 (3.98 percent) were still using the obsolete Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) protocol. That's significantly better than San Francisco's 9.5 percent, which presumably has so many obsolete wireless networks because it rolled them out sooner, but it's still a worry.

"WEP is just broken, bad, has been known-bad for such a long time, and there really isn't a context in which it should be used now — and it's still remarkably present," Lyne told ZDNet.

"Yes, we're talking single digits, not double, but these are thousands of networks in 2014 that anyone can break into in a short period of time. And worse still, these people have a password, so they think that they are safe."

The newer WPA protocol was used by 9,704 of Sydney's networks (28.15 percent), WPA2 by 15,177 (44.02 percent), and WPS by 11,981 (35 percent).

Open networks accounted for the remaining 8,224 (23.85 percent). Many would be captive networks belonging to hotels and other semi-public providers, requiring a further login, but without any encryption they can expose users' network traffic to monitoring.

"You can see that a security problem that's over ten years old is still a major issue for society," Lyne said.

So why is this?

"I think there's definitely an element of geeky ADHD, and as a researcher I absolutely understand that you want to find the latest interesting thing ... the latest exploit, the latest vulnerability," he said. "You don't get a Nobel Prize for going back to a wireless security issue of 15 years ago and stating the obvious, that it's still a problem."

Infosec vendors also need to generate a constant stream of new things to talk about to attract media attention. A new threat, or a new way of organising network defences, even just a new buzzword to describe existing concepts, all provide a new reason to contact potential customers, and a new justification for them to spend more money.

"I think sometimes we forget that our objective is to get this across to members of the public that really have very little context about what we do day to day, and we forget that real good comes when we change behaviours, when we change the underlying technology and actually fix these problems — as opposed to just going, 'I'm smart. I found a thing,' and moving on to the next thing," Lyne said. "People are quick to pass over the human and social element. Maybe some of that is the commercial nature of the security industry. I think a larger part of it is [that] many of us who work in research and actually understand what is going on aren't necessarily always the most talented at dealing with actual people."

So how do we fix this?

"First off, we have to actually educate people that they do need to go back and look at this stuff more frequently, and that you can't just use something for ten years and expect it to be secure," Lyne said.

"Secondly, as a community of security professionals, we have to get better at giving actual clear, simple advice." No jumbles of jargon and justification, just a concise explanation of the risk, and how to fix it — with specific instructions.

And finally, Lyne says, we need to call manufacturers to task.

"We should be planning auto-update. We should learn from the fact that people do not make these changes, and try and make it really simple to facilitate this stuff for them. Think about that now in the context, not only of this wireless kit, but think about smart grid devices [and] all of these internet of things devices getting deployed in our homes. Most of them are being built with a very 1990s mentality, as opposed to learning from our mistakes and engineering for failure — because I can guarantee you, there will be security failure in these systems."

Well, I've already warned of the impending refrigergeddon and how we know how to avoid it, but I'm inclined to agree with my colleague Chris Duckett, who thinks refrigergeddon is inevitable because we won't bother fixing the Internet of Broken Things (IoBT) until a disaster happens.

On another happy note, we might also be facing routergeddon.

According to Dimension Data's annual Network Barometer Report 2014 released today, the proportion of ageing and obsolete devices in corporate networks is at its highest in six years.

"The conventional assumption was that a technology refresh cycle was imminent. However, our data reveals that organisations are sweating their network assets for longer than expected," said Gregg Sultana, Dimension Data's national manager for networking, in a press release.

"We believe that the advent of programmable, software-defined networks may be causing organisations to 'wait and see' before selecting and implementing new technology — a factor we expect will become more influential in the next 18 to 36 months."

I wonder how many of those rickety old corporate networks, with their wireless SSIDs conveniently set to the company's name, still run WEP, or are still unpatched against ancient vulnerabilities. I suppose the bad guys already know.