After WannaCry, ransomware will get worse before it gets better

WannaCry played havoc with systems across the globe: what can we learn from it?

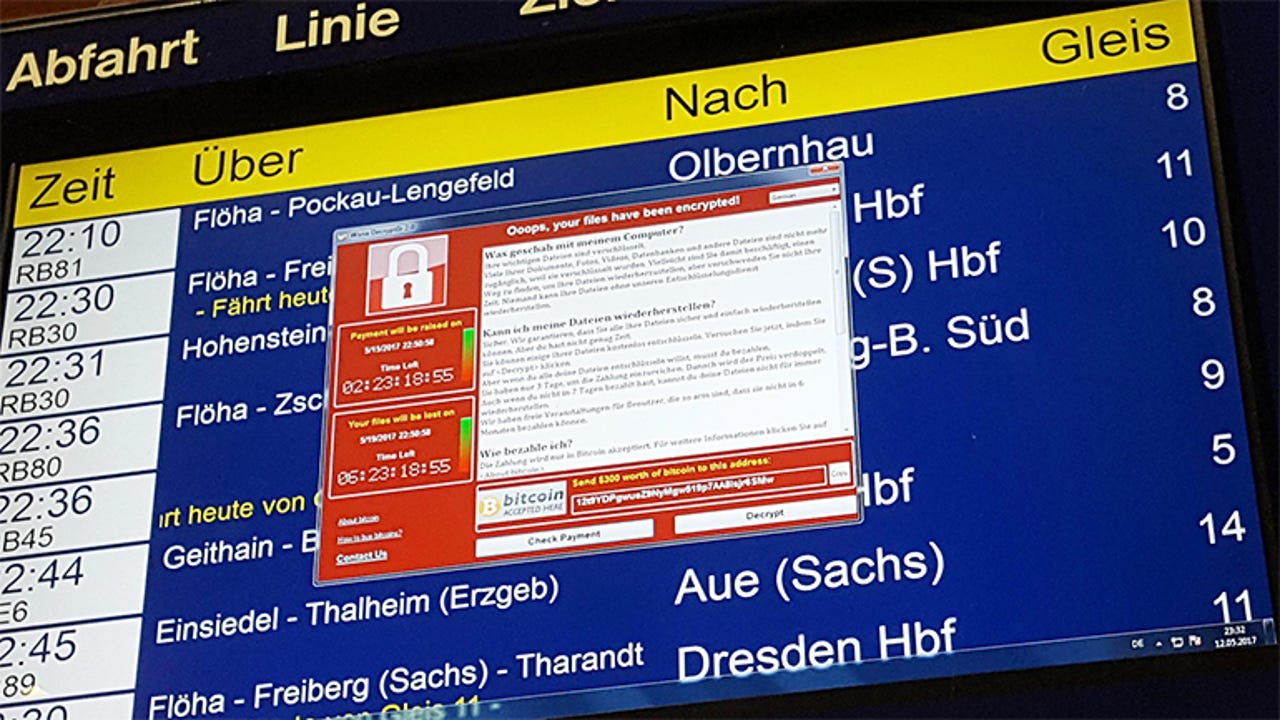

The WannaCry outbreak put ransomware into the global spotlight, generating global coverage across mainstream media outlets as the malware epidemic locked governments, hospitals, public transport networks, factories and more out of their computer systems.

Thanks to its worm-like features, WannaCry was able to quickly spread itself across an infected network, taking advantage of a vulnerability in some versions of Windows. Over 300,000 Windows PCs succumbed to the ransomware before the outbreak was brought to a halt when a kill switch was discovered. But plenty of damage had already been done, with billions of potential revenue lost.

All of this was caused by a rather basic form of ransomware that came to life after haphazardly being bolted onto EternalBlue, an NSA-built exploit leaked by hackers. Researchers have suggested that we're lucky that those behind WannaCry appear to be rather amateurish, because a slick operation using more advanced code could have caused much more damage.

Just imagine if WannaCry had come with Locky- or Cerber-grade encryption...

Ransomware in the spotlight

Nonetheless, the global impact of WannaCry has thrust ransomware into public view in an unprecedented way, despite it generating $1bn in 2016 for cybercriminals.

"We've turned a corner; it's an unfortunate reality that it takes bad news to create awareness, but it is a reality," says Darren Thomson, CTO and VP of Technology at Symantec, who notes that the 'real-world' impact of the outbreak is what has got people talking.

"The day WannaCry happened, at the same time I was getting notified by our global intelligence I was getting texts from my mother who was in hospital who couldn't check in because of the problem," he says.

So what's next for ransomware after the infamous WannaCry? After all, cybercriminals are developing new families of malicious code all the time.

One security expert believes that WannaCry, by not even having the ability to unlock the files of those who paid the ransom, could be the beginning of the end for ransomware because it has broken the 'trust model' of the criminal scheme.

"Ransomware is one of those crimes which relies on an 'honest' criminal, "says Rik Ferguson, VP of Security Research at Trend Micro.

"It relies on the fact that if you pay the ransom you get the data back, and the more it becomes apparent that you pay the ransom and don't get your data back, the less likely you are to pay the ransom."

"That could be the single biggest silver-lining to do with WannaCry; it may have killed the goose which laid the golden egg from a criminal perspective," says Ferguson.

But that might be wishful thinking, because WannaCry was unique and while the security industry will tell people that they need to take additional precautions, the public will likely be back to business as usual soon enough.

"I don't buy it that the ransomware in general will start to see a decay because of the publicity of WannaCry," says James Lyne, Global Head of Security Research at Sophos.

"I'd love to think that means that everyone has backups, everyone is prepared to follow the ethics of not paying cybercriminals and make it a crime which doesn't pay. I'd love to see it, but it won't happen."

See also: How to defend yourself against the WannaCrypt global ransomware attack| Ransomware: An executive guide to one of the biggest menaces on the web

More advanced ransomware

If anything, ransomware is going to become more advanced, harder to decrypt with free tools, and things are going to get worse before they get better -- before enough individuals and organisations learn to not to pay ransoms, or to protect their systems with backups.

"I think we're going to go through a period of much more painful ransomware before that happens. I think we're still on the up, rather than the drop," says Lyne.

"We're going to go through a period of ransomware authors having much more robust crypto, robust payment channels, the death of decryption tools which help people get their data back without paying".

And even now, despite some ransomware variants being inherently poorly built, ransomware is working because victims are giving into ransom demands, with some figures suggesting that as many as two-thirds of victims will pay up.

As a result, cybercriminals know they can get away with charging higher ransom demands -- helped along by the rocketing value of Bitcoin, the most common form of currency used to exploit ransoms.

"The average size of ransoms has tripled in the last year, because it's supply and demand. If a criminal can charge more because they know they're going to get a return, they will," says Thompson.

He calls it "worrying dynamic" especially because "this would die tomorrow if people stopped paying, because there'd be no return on investment whatsoever."

"One of the reasons we see so many people paying ransoms is they're hearing stories of other people being attacked who have got their data back. In the case of WannaCry, they didn't at all, so it should show that paying is never a good idea," Thompson adds.

However, WannaCry, despite being massive, was still just one outbreak and lessons about not paying aren't going to be learned from just a single incident.

"If we had 30 WannaCrys over the next year and it became known that you never get your data decrypted, over a long period time and after a lot of pain the dynamic would start to change as people start to stop paying," says Thomson, while noting that such a number of catastrophic incidents is unlikely.

Be prepared

That's not to say something along the lines of WannaCry won't terrorise the world again in the near future, with new strains of having spotted in the wild and the exploit behind it even powering Trojan malware. Next time, it could be the work of a much more professional outfit.

"These government agencies obviously have offensive weapons like these. Remember Hacking Team? They got hacked," says says Marcin Kleczynski, CEO of Malwarebytes.

"They had something like ten exploits; ten really good exploits that they sold to the highest bidder. In the wrong hands they get weaponised and used for a ransomware attack or disruption instead of spying."

That means future ransomware attacks like WannaCry are very much on the cards. "My hypothesis is we'll see two or three more of these attacks this year -- if not more" he says.

Given how unprepared many organisations are to deal with even the most basic ransomware attack, this could potentially spell disaster for some.

"If people don't prevent the impact by proactively preparing with the right security controls, patches and backups, we're going to have many more people in positions of irrecoverable data loss if they don't pay," says Lyne.

But maybe, just maybe, the notoriety of WannaCry could give some organisations that extra push they need to ensure they are protected against future ransomware attacks.

"It's made people aware that even if they do pay the ransom there's no guarantee they'll get their data back, and that they do have to focus on other forms of recovery and mitigation from those kinds of attacks," says Ferguson, arguing that mainstream coverage of the outbreak has pushed ransomware outside of the security industry.

"Hopefully people are going to pay a little more attention to vulnerability management, patch management, legacy systems," he says. "I think there's a lot of good stuff which is going to come out of WannaCry".

READ MORE ON RANSOMWARE

- Ransomware attack: How a nuisance became a global threat

- Microsoft warns of 'destructive cyberattacks,' issues new Windows XP patches

- Hackers behind stolen NSA tool for WannaCry: More leaks coming [CNET]

- 3 best practices for protecting yourself from WannaCry and other ransomware attacks

- Don't be the weak link that brings us all down: Keep your OS patched and up to date [TechRepublic]