Can GIMP replace Photoshop?

Almost everyone has heard of Adobe's Photoshop, but far fewer people have actually paid for it. With prices necessarily high to combat piracy of its flagship application, Photoshop is beyond the reach of most casual users. Even professionals in small businesses may find the program's list price of £485 (ex. VAT) prohibitively high.

Fortunately for the budget-strapped, there are alternatives to Photoshop, some of which cost absolutely nothing. The most popular is the open-source project, GIMP (GNU Image Manipulation Program), which has won many fans over its several years of development.

But can you really replace Photoshop with free software? For basic operations, an advanced application like Photoshop certainly isn’t necessary — even professionals, who use the program daily, often make use of only a fraction of its capabilities. Only a small subset of Photoshop’s features is required for everyday tasks such as editing pictures for web use or retouching photos from digital cameras; much simpler applications, including free ones such as GIMP, can do the job just as well.

GIMP is a favourite among Linux fans, coming preinstalled or easily installable on many distributions. It's also available for Windows and Mac OS X. For many people, GIMP offers all the image manipulation tools they need: most of Photoshop's core functions are present, and its functionality is being expanded all the time. In this article, we examine just how far a serious (professional or semi-professional) user can get with GIMP.

Basics

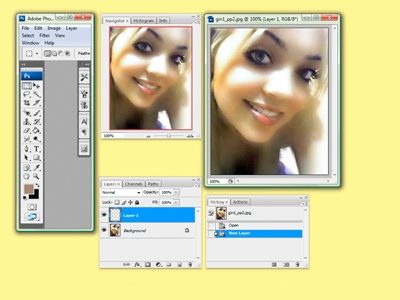

If we consider a simple task such as editing a digital photograph, it's clear that Photoshop and GIMP can provide very similar working environments.

Obviously there are some differences in layout and terminology and, as you delve deeper, you may notice some bits missing from GIMP as well as usability differences. However, the navigation, layer and history palettes are all essentially the same in both applications.

What can’t GIMP do?

Although new features are being added all the time, GIMP is currently missing some major features. Some of this functionality isn't essential — it may make life easier, but with a little effort it can be lived with. Some missing features can be added via plugins and extensions, but inevitably some users will come across show-stoppers — features without which they simply can't do their jobs.

So let's start with the biggest issues, bearing in mind that the goalposts are constantly moving: if GIMP doesn’t do it already, then there’s probably someone coding away furiously to make it happen, be they part of the official development team or not. However, for now, if you absolutely need the following features, then GIMP won’t be of much use to you.

Bit depths higher than 8-bit

When using GIMP, you’re restricted to images with 8 bits per channel: for an RGB image, 8 bits per channel gives 28x28x28 = 16,777,216 colours. Although the vast majority of digital camera images use a maximum of 16.7 million colours, advanced users often need to use high bit-depth images of 16 or more bits per channel.

Examples of such images can be RAW or TIFF images from digital cameras, as well as those produced by high-end scanners. Today, it’s popular among both hobbyists and professionals to make use of RAW images as digital SLRs keep falling in price and HDR (High Dynamic Range) photography increases in popularity.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to be able to work with any of these types of image in GIMP. But don’t despair: A fork of the GIMP project, originally known as 'Film GIMP', is designed specifically with high-bit depth processing in mind, and is used in many high-end professional environments such as movie-making. It’s now known as Cinepaint and you can download this software free of charge. Although it’s aimed primarily at retouching movies and comes with support for various esoteric industry-standard file formats, you can also use it to process high bit-depth images from professional-level cameras and scanners.

The code base for Cinepaint forked away from GIMP several years ago, and has not seen the same level of development. So if you work with both 8-bit and high bit-depth images you may find you need both packages to get all the features you need.

No CMYK

If you use Photoshop to create artwork for print, then you can forget about replacing it with GIMP for now, as GIMP supports only RGB colour. CMYK support is due to be added, but for now it's not available. If you’re sending artwork or images off to repro, they’re going to want everything in CMYK mode; and if you want to see on-screen how things will look on paper, you’ll need a CMYK preview mode. Furthermore, Pantone colour requires licensing and is therefore unlikely to be included in a free software package, so there’s no industry-standard spot colour capability.

The lack of CMYK therefore makes GIMP unsuitable for use where you’re producing professional work for print. It’s still absolutely fine for printing on your inkjet at home or at a kiosk, as these printers use RGB drivers anyway. Lab colour is also missing from GIMP, leaving you with only device-dependent RGB to work with, which brings us on to the next missing feature.

No colour management

Accurate colour reproduction is critical for imaging professionals, and Photoshop takes full advantage of the colour management support available in Windows and Mac OS X.

Full support for ICC and ColorSync profiles means that you can guarantee consistent colour from one PC to the next. This means you can create accurate — or at least repeatable — soft proofs, predicting with some degree of certainty what colours will end up in print or whatever your final delivery medium might be.

As standard, the GIMP has no support for colour management, although attempts have been made to incorporate it via plugins. The good news is that the forthcoming version 2.4 release of GIMP will incorporate native support for colour management. Current releases of CinePaint also support colour management on Linux.

Colour management is something no-one wants to have to worry about, and much work has gone into making it happen mostly behind the scenes in Windows Vista. Unfortunately, when it’s not happening at all, getting your photos to look right can result in you attempting all sorts of strange adjustments to compensate for your poor monitor, or the fact that you’ve loaded a photo from a camera set to Adobe RGB mode.

Usability issues

If you can live without, or don’t need, any of the features above then you may find that GIMP is just the application you need. It has a much smaller footprint than Photoshop on your system, and won’t cost you anything to use.

However, even when a given feature is available in GIMP, you may find that Photoshop can do the same thing better. For example, performing a levels adjustment in Photoshop results in a live preview that changes before your eyes as you move the relevant sliders. Performing the same function in GIMP, by contrast, requires you to let go of the slider each time you want to see the effects of your adjustment.

If we take a look at the brush tool in each application, we can see that Photoshop’s offering is more sophisticated:

GIMP allows you to create custom brushes of any size, but in Photoshop you can resize brushes dynamically while you’re using them. This is an invaluable time-saver, especially when creating masks, as you don’t have to go and specifically create a new brush whenever you need a new size.

Other features in Photoshop offer a great deal of convenience, but you can generally get by without them. Functions such as the healing brush, layer effects, layer folders and recordable actions are a boon to heavy-duty users, yet many never use them.

Adding functionality to GIMP

For those who do need more than the standard package provides, there’s a whole world of plugins and add-ons for GIMP.

Although Photoshop just installs out of the box and is ready to go, to get advanced functionality out of GIMP requires some effort on the part of the user. Some standard Photoshop features are possible in GIMP, but require the installation of additional software.

It’s the nature of open-source development for different development teams to be working on related projects. What this means for the user is that you often won’t find what you need all neatly packaged up in one place. The functionality you need may be available, but you may have to spend some time finding it and then getting it to work.

Using Photoshop plugins

There are many freely and commercially available plugins for Photoshop, and if you already use these, you’ll be please to know that of these can be made to run successfully in GIMP using a plugin called PSPI.

PSPI was developed in 2001 and was recently updated (in 2006) to run not only on Windows, but also on Linux. It uses Photoshop’s plugin SDK to form a bridge between the two plugin formats, thereby allowing you to load up Photoshop plugins directly in GIMP.

GIMP’s interface is different to Photoshop

GIMP was never intended to be a Photoshop clone, and so it doesn’t use the same menus, keyboard shortcuts or terminology. If you’re used to Photoshop, then although GIMP is relatively straightforward to use, you’ll find the user interface and control system rather different. To help Photoshop users make the transition, GIMPshop takes a normal GIMP installation and modifies it to look more like Photoshop.

By mimicking Photoshop’s menu layout, GIMPshop aims to make GIMP simple to use for Photoshop users, although it’s not officially supported by GIMP’s developers.

Coming soon to GIMP

As with most open-source projects, GIMP is under constant development and new features are being added all the time. Development releases, with version numbers 2.3.x, have started to incorporate some level of colour management by supporting embedded colour profiles when loading images. This is still very much a work in progress, and we should not expect to see a sophisticated colour management solution anytime soon.

One of the proposed systems for supporting colour management in GIMP is LittleCMS (LCMS) which has been ported to Windows, Mac OS and Linux platforms. You can follow the development of GIMP, by checking the developer site.

Conclusion

So can free software really compete with Photoshop? For the vast majority of ordinary users the short answer is certainly 'yes'. However, for graphics professionals — that is, Photoshop’s target market — the answer has to be a resounding 'no'.

There are many people who are using Photoshop, legitimately or otherwise, who would be served just as well by software such as GIMP or its derivatives. Those wishing to learn image editing can also gain much from using GIMP, especially as GIMPshop enables many Photoshop tutorials to be run on GIMP.

But GIMP has a long way to go before it can gain a strong foothold in the industry. Although CinePaint has found a niche market in professional movie production, wide acceptance of GIMP would require major work if it’s to be relied upon by those who would make their living from it — especially if they are creating work for print.

Many of the required features are already in development, and if they’re implemented successfully we should see more people being able to create and edit their work entirely on free software. This has to be a good thing for everybody — except perhaps Adobe.

Ultimately, though, there are some proprietary technologies that simply must be paid for — Pantone support being a good example. Until we see free alternatives with widespread industry support, we’re going to have to pay for software that licences such technologies.