Consumer-Generated Pricing: Foundations of a democratic patronage

Any band that doesn't fit these existing price systems, because their audience is "too small" or too far-flung to be served efficiently is typically left out and on their own, seeking a channel for their music that allows them flexibility in pricing. This is an aspect of the foundational problem of "consumer-generated media" on YouTube, Revver, MySpace and every other site where new talent attempts to address an audience.

A while back, I asked you how much a Web star, such as Ze Frank of The Show With Ze Frank, should be able to earn from their work. An overwhelming number of respondents to that poll said "The sky is the limit." Ze Frank found some interesting ways to make money, selling icons that serve as a kind of day sponsorship analogous to public radio, but he's still guessing at what people might pay him, if they had the chance to decide. Donation systems, while interesting, lack the force of social expectations, so they fail to provide a sustainable flow of payments.

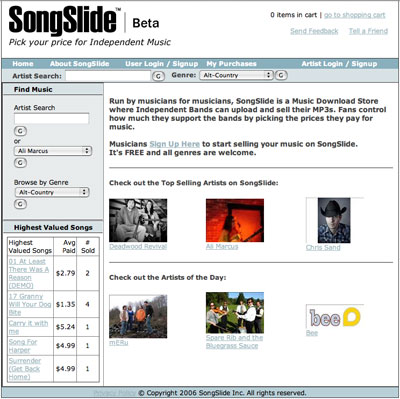

So, I was very intrigued to hear from the guys at SongSlide.com, Devin Brewer and John Hurd, musicians from Seattle who decided that they needed to find a better way to let fans of music support the bands. Their tagline is "pick your price for independent music." Setting a minimum fee of $0.59 per song (which is a function of having to generate transactions of a certain size in order to be able to use processing services like PayPal), SongSlide lets fans of new music set their own price, and, typically, they pay more than three times the minimum price for a song. Artists earn an average of $1.93 a song.

Still in beta, SongSlide has about 100 bands signed up and using the service. Especially interesting in this Digg-powered marketplace of ideas we live in is the daily listing of songs earning the most, which is displayed on the home page and currently depend on very small volumes to calculate value. This kind of social pricing information can become a very sophisticated foundation for fans to support the music they love.

In the past, before corporate music came along, patrons of the arts were the primary makers of taste. They supported works and artists, allowing them to build an audience over long periods of time. Out of that, we got some fine culture. Corporate music and arts, too, have produced some good stuff, but the limits on creativity have only increased in proportion to companies' concerns about the cost and risk associated with new ideas and technology, so we get fewer and fewer really new kinds of music, art, writing and performance.

What SongSlide represents is a kind of "new patronage" in which everyone can participate. If you love a particular performer's work and can support it with higher payments, you create longer runways for their success to take flight. With this approach, much distributed by the Web's ability to link creative people and audiences, it would be possible to pay a lot for an artist's work early in their career so that, later on, you get lots of music (or film or whatever) from them at lower prices due to market efficiencies. Then you can support new artists and pay just a little to the established stars.

A democratic patronage would spread economic benefits more efficiently, because it would help defray risks for younger/earlier artists, who, in turn, could afford to live well on very small payments from the larger audiences they build over time.

Look, if everyone who hears the Rolling Stones this year gave the band a penny twice a year, Mick and the Boys would double their current revenues from sales. But its out in the cultural weeds, where new stuff is cooking, that we most need to get the nourishment of revenue. If small groups within the same audience that gave a little to The Stones could give 100,000 less successful artists than the Rolling Stones $10.00 twice a year, we'd have a far richer culture. And avid customers who successfully build the audiences for the bands they follow could become part of the value flow, as well, just as influential Digg members are beginning to do. The marriage of aesthetic and economic interests has consistently produced real quality in the arts, Berlioz notwithstanding (curse you, Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, for your patronage of Berlioz).

The challenge for SongSlide will be to make its system accessible through APIs as quickly as possible, so that it can allow artists and audience to connect and determine the prices to the greatest extent possible. The founders tell me they believe they can eliminate their minimum price requirement after they achieve a certain volume of transactions and, at that point, the system seems ideally suited to solve problems in music, video, movies and other creative markets. However, at least one cafe in the Seattle area, owned by a Google engineer, is trying a pay as you see fit approach to food. I think this form of pricing is most applicable to titles and services delivered over the Internet, because food and hard goods come at a fixed price based on the supplies needed. Creativity, once produced, can be copied without any additional costs, so the producer must learn to start small and build their audience up to blockbuster production costs.

SongSlide has filed a patent for consumer-generated pricing that can be applied in a variety of markets, including music, video and other forms of artistic and creative work that depends on digital replication rather than physical goods. This is one to watch.