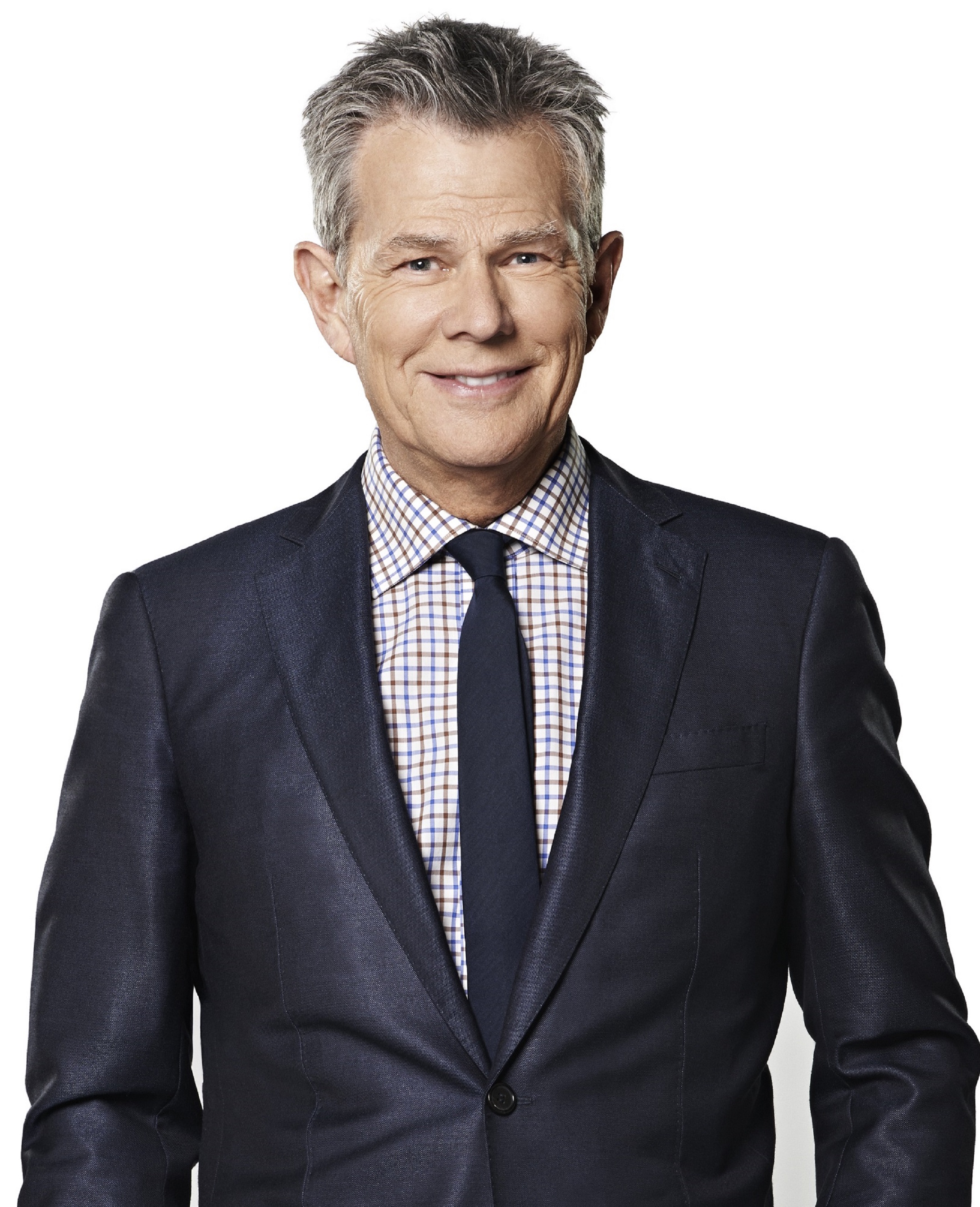

David Foster's utopia reflects digital music dichotomy

Given a chance to go back in time, David Foster would emphatically say no to the internet.

The multi Grammy Award-winning songwriter and music producer readily admits the digital era has impacted the world significantly, but notes that it also has greatly damaged the music industry.

I recently sat down for a chat with the effusively charming 65-year-old who was in Singapore for talent show Asia's Got Talent, for which he was a judge. The first question I fired off was how he thought the music industry had gained from the internet evolution and had intended to follow that with what he thought the industry had lost as a result of the internet.

I was expecting him to herald the digital age as one that had made music more accessible, allowing more people around the world to hear the music he created. I also expected the maestro to champion technology for enabling him to create songs more efficiently.

Instead, Foster related how someone had once asked if he had a chance to go back in time, would he say no or yes to the internet. "I would say no," he continued. "It's the greatest change that we've seen obviously. It is exponential and influential...but the internet has really hurt our business."

While the music business in itself was still doing great, the record business isn't faring as well, he said. At its height, the industry was a US$40 billion business but revenue had been on a steep decline over the last 15 years, he noted.

Figures from the International Federation of Phonographic Industry (IFPI) put recorded music sales at US$40 billion in 1999, dipping to US$15 billion in 2014.

Despite the dismal numbers, Foster is optimistic that industry stakeholders will figure out a way to revitalize the market. "Streaming obviously is the way it's going to go, but if everyone plays by the rules, we may be an even bigger business than before," he said. He added that most music lovers would have little qualm paying $10 a month to access any song they wish, and at any time.

"And it's easy access," he said, pointing to the days when even software pirates would have to sieve through a wave of dummy or corrupted files to download a usable, but illegal, copy of the song they were looking for.

With easy and affordable access to music streaming services such as Spotify, fewer people now choose to download pirated copies. The music industry, however, still needs to plug some pretty big holes.

Foster pointed to the likes of YouTube as the "biggest crusher" of the music industry. "The company that really needs to get their s*** together is YouTube," he said, noting how easy it was to freely access music on the video-sharing website. "It's not right that your song can be heard a hundred million times on YouTube and you're not getting paid for it."

He admits, however, that he himself is guilty of tapping YouTube when he needs to reference, for instance, a particular drumbeat he had heard in a song. He stresses, though, that he is willing to fork out $100 a month if the video site started charging a fee to ensure due revenue makes its way back to the rightful stakeholders.

"I happily pay Spotify money and pay a lot more to not see ads on YouTube, but I realize I'm in an upper income bracket," he said, adding that he stopped buying CDs years ago, and currently accesses music via Spotify and other legal downloads.

It's clear Foster's biggest beef is that artistes aren't getting back the appropriate amount of revenue their music is generating on third-party platforms, which really doesn't deviate from others in the industry--notably, Taylor Swift. The singer pulled her albums from Spotify and suggested artistes weren't paid their due worth via the streaming site.

Swift said: "Everybody's complaining about how music sales are shrinking, but nobody's changing the way they're doing things. They keep running toward streaming, which is, for the most part, what has been shrinking the numbers of paid album sales."

According to IFPI, digital music revenues worldwide grew by 6.9 per cent to US$6.9 billion last year putting it on par with physical music sales for the first time, with each accounting for 46 percent of overall revenues.

Spotify says it pays 70 percent of its revenue to recording companies, handing over US$1 billion alone last year. Between its debut in 2008 and 2013, it coughed out another US$1 billion in royalties. CEO Daniel Ek wrote in a blogpost following Swift's departure: "We've already paid more than US$2 billion in royalties to the music industry and if that money is not flowing to the creative community in a timely and transparent way, that's a big problem."

So perhaps the real issue is that the money isn't trickling down to the artistes, and the bottleneck lies with the labels.

And not every artiste has a bone to pick with Spotify. Flavor of the month singer-songwriter Ed Sheeran is a vocal supporter of the streaming site. At the BBC Music Awards last year, 24-year-old Sheeran said: "I'm playing sold-out gigs in South America, I've sold out arenas in Korea and Southeast Asia. I don't think I'd be able to do that without Spotify.

"For me, Spotify is not even a necessary evil. It helps me do what I want to do," he said, adding that he felt royalties paid out to the artiste community were fair. He, too, suggested that the monies were locked out by recording companies.

However, he noted that selling CDs was no longer the main source of income for many of these artistes, pointing to concerts tours as the main revenue stream."I think Spotify are paying the right amount... We're just not seeing it because the labels aren't making as much as they used to, so they want to keep a lot of the money that Spotify gives them," Sheeran noted. "I get a percentage of my record sales, but it's not a large percentage. I get [the profits from] all my ticket sales, so I'd rather tour."

Foster couldn't explain the contrary views of Sheeran and Swift, both of whom belong to the same generation of musicians. He did reveal that he paid for downloads of Swift's 1989 album when he couldn't find it on Spotify. "So, it worked for her, right? Because I went out and bought her album," he quipped.

Will it require everyone working as one?

So what will it take, I asked Foster, probing him for what he thought was the ideal model for digital music consumption that would work for all stakeholders involved.

He pitched the idea of record companies and artistes as equal partners in the entire music-making process, so "we're all in it together" with the label making half of every dollar the artiste makes, while the other half goes to the artiste. "It's one where everyone is working together for the same cause. The record company has to earn that half," he said. "The notion of record companies putting in all the money, all the risks and millions of dollars [to support the artistes], and only have a small share of the album sales is a dinosaur model."

I'm assuming this model includes a shared cost structure where record companies also pay for the cost of hiring the band, managers, lawyers, producers, and so on.

According to a BBC report, some independent labels are already supporting the 50-50 revenue model, particularly in digital music sales.

And unlike Swift, Foster supports the concept of streaming and believes the model can be fixed, for instance, through higher awareness and educating people about the value of paying for their music.

"Most kids would suffer through an ad to get to music as opposed to paying a premium price for it. We have to educate the next generation of music listeners," he said, while acknowledging that "people love free s***". "We're all addicted to free [but] it can't continue like this."

It's interesting to note here that, despite its apparent success, Spotify is yet to be profitable. It states that it has more than 15 million subscribers of its paid Premium service, which accounts for 20 percent of its overall active subscriber base that totals more than 60 million active users. The streaming service offers more than 30 million songs, adding 20,000 more each day, and is available in 58 markets including Singapore, Australia, Hong Kong, and the Philippines.

Industry observers believe the streaming site needs to restrict its free service tier, but Spotify has insisted this model is essential to converting users to its paid service.

Jonathan Foster, head of Spotify's Nordics region, said in an FT report: "Without free, pay has never succeeded. We're one of the greenest shoots of growth in the industry. We don't want to destabilise that. We think that this model works."

Ek further explained in his post that Spotify helped eradicate music piracy, offering a "freemium" model that balanced the needs of both the free and paid worlds:

The paid-only services never took off, despite spending hundreds of millions of dollars on marketing, because users were being asked to pay for something that they were already getting for free on piracy sites.

The free services, which scaled massively, paid next to nothing back to artists and labels, and were often just a step away from piracy, implemented without regard to licensing, and they offered no path to convert all their free users into paying customers.

Today, people listen to music in a wide variety of ways, but by far the three most popular ways are radio, YouTube, and piracy--all free. Here's the overwhelming, undeniable, inescapable bottom line: the vast majority of music listening is unpaid. If we want to drive people to pay for music, we have to compete with free to get their attention in the first place.

Dichotomy of digital music industry, consumers

Therein lies what I believe is the main challenge facing the industry: there will always be pockets of consumers who like to access their music differently--be it via free streaming service or paid downloads, or even CDs.

I belong to the old school of music lovers who want to own their music, rather than access it only as a streaming service. In fact, I just bought Sheeran's X album on CD a couple of weeks back and regularly purchase iTunes downloads when I prefer to buy single tracks off an album. It's the primary reason why I'm not a user of Spotify.

"But that's only because we're old school, we like to own [our music]," Foster said, when I told him about my preference. "Kids today don't want to own, they couldn't care less. They just want to hear it."

He's right, of course, and there also are folks out there including Foster who still turn to "free" services like YouTube because there isn't a better paid option.

Clearly, there is no easy solution.

Foster's utopia requires record labels and artistes to work together toward a similar cause, but this won't work either if consumers aren't along on the same ride. And they'll feel little need to do so when they see artistes drenched in expensive gowns and lapping up the high life on an island in Hawaii--while, under the same breath, lamenting how they're not getting their due revenue.

Perhaps Spotify does need to tweak its freemium model, for instance, by restricting the number of times users can listen to a song for free, so they will have to upgrade to the Premium tier if they want to play their favorite song on a loop. It could also limit the songs that are available on the free service, for example, where only Top 40 songs for the week are available, and make any albums or songs released more than six months ago accessible only on its Premium service.

I also believe artistes and musicians should earn their keep the way previous generations did, by hitting the road with concert dates and touring. After all, the likes of Madonna and Swift must earn the bulk of their income from their high ticket prices.

Whatever the answer may be, ultimately, industry stakeholders will need to consider the varying consumer needs and make as many accessible to them as possible. Above all, give consumers--regardless of their age group--a reason big enough for them to want to pay for their music.