Facebook and employment: an equal opportunity information trap

I had a number of follow-up questions for George after reading his series, and he was good enough to provide answers. Our discussion follows, as well as links to the series itself.

My first question was about whether fine-grained privacy controls solve the problem: if a person's social networking data is sufficiently restricted does this become a non-issue? George says not necessarily.

Denise: One thing I don't see addressed: one of the most powerful features of Facebook (and a host of other social networking sites) is the fine-grained privacy control users have over the visibility their data. Often, only "friends" have access to the kinds of details George discusses. But, lots of people do make their data more generally visible. It's ironic that employment laws are such that though "the public" may be invited to view such information, lucrative damages awards or settlements could be associated with doing so in the context of employment or potential employment.

George: The Wall Street Journal recently had a column on what to do if your boss wants to be your "friend." Extremely close to home (where my daughter works), a bunch of kids got fired last week based on pictures posted on facebook. They may have been on a "friends-only" profile, but the URL history trail of kids viewing them was left on a work computer, and, in any event, one of the managers was a friend of the poster so would have had legitimate access. It seems the privacy controls do provide a legal basis for "reasonable expectation of privacy" claims, but as a practical matter there may be fairly simple ways of getting around them. Such as using a computer that has a password memorized in order to gain access, essentially impersonating that user. Probably illegal, perhaps under federal computer fraud and abuse act, but you may lose your job or not be hired without ever knowing that this snooping occurred and was the reason why.

I next wondered, since George's series focused on the hiring process, whether the same concerns also affect existing employment relationships and potential wrongful termination claims. Yep.

At first I only thought about the hiring context because this was the manner in which the question was posed to me by Steve Rothberg of collegerecruiter.com. Yet I had previously done a series on termination of bloggers.

In my career representing employers in employment law matters, termination cases have dominated over everything, except perhaps sexual harassment. I suspect when someone is not hired for a particular position, it is not perceived as such a damaging event compared to termination, although both result in lost wages. Nonhiring is so much more frequent of an experience for job seekers than termination for employees. And reason for suspicion of employment law violations is less likely to be apparent. Arguably, proof is also more difficult. If there were a thousand applicants for one position, how do you rebut the employer's contention that someone else was better qualified?

In any event, I think the concerns about the lawfulness of accessing personal information are pretty much the same for termination as hiring.

One exception would be that a current employee has probably given up any expectation of privacy in Internet activities that take place using the employer's computer systems. It is certainly a routine element of a recommended employer policy regarding computer systems to inform employees that their usage may be monitored. In other words, for reasons predating blogs and social networks, employers have had reason to take steps to defeat any claim of employee privacy rights with respect to use of employer systems.

In the incident I mentioned involving my daughter's coworkers, such waiver of privacy rights was probably a crucial element It is my understanding the employer found the damning evidence because the employees had viewed it using the employer's own computers, which the employer then had a right to access (or assumed that such right).

Applicants would not have waived their privacy rights (if any exist) in this manner.

The discrimination issues would also be the same to a considerable extent, with one obvious difference. With applicants, I expressed concern about "too much knowledge," referring to gaining information about applicants via Internet that could be claimed to have given rise to discriminatorily motivated decisions -- and doing so at an earlier stage in the application process, sacrificing the employer's ability to use the defense of ignorance (e.g."I didn't even know he was black"). Obviously, with a discharge of existing employees, this defense is less likely to be available (though it was at issue in a case that was almost decided by the Supreme Court – search "cat’s paw" in my blawg if you’re curious).

Back to the question of privacy controls and restricting data access to "friends," I was curious about the enormous professional networking role played by the social networking process. Many understand, and indeed fervently anticipate, that their social networking efforts will play a productive role in their professional life. In such an ecosystem, employers, potential employers, or their representatives routinely have "friend" access to data a person might otherwise restrict. George thinks employers in this sort of relationship would likely escape discrimination or privacy related liability, but it's not a slam dunk.

It seems that making someone a "friend" waives any conceivable privacy claim as to the information you have made available to "friends," regardless of the purpose for which they use the information. That is, the "friend" is not invading a privacy interest if they access the profile and directly use information on it. However, the election to limit the information to "friends" creates a privacy interest as against all non-friends. This interest might be violated if a "friend" communicated the information to others for purposes of employment decision-making. In this regard, it is not equivalent to "the candidate volunteering the information." It's as if I said "Denise, confidentially, just between you and me, my parents are Jewish"; not as if I said "my parents are Jewish."

Along these lines, I also wondered whether it would make a difference that a candidate's "friend" was not directly involved in the hiring process, but perhaps just shared the information with those who were.

Yes, as I indicated, I think passing it along is different than directly using it. So if the friend is the sole decision-maker, or if the friend keeps the private information to himself/herself, but recommends the "friend" as a candidate without mentioning such information, I see no privacy issue. Of course, the "too much information" problem applies to anyone who gains the sensitive information in any manner — including "friends."

Finally, George offered this:

I just found this, in a Jay Parkhill post citing my blog: "Permission to one use does not mean permission to others, but the technical tools can’t always recognize these distinctions. A friend can give me special permission to see his/her semi-private Flickr photos. Do I violate my friend’s copyright or privacy rights if I stream those photos to my own blog- with unrestricted access? Probably yes, is the answer. Given how easy it is to do that, what are the consequences and how can we address it? Good questions- no sure answers."

Seems a bit analogous to what I said about using your "friends" access to provide info to your employer, which is contemplating hiring your "friend" (ironically, perhaps on your recommendation). Your "friend" granted you permission as "friend" to view, but not necessarily to transmit to your employer in this context.

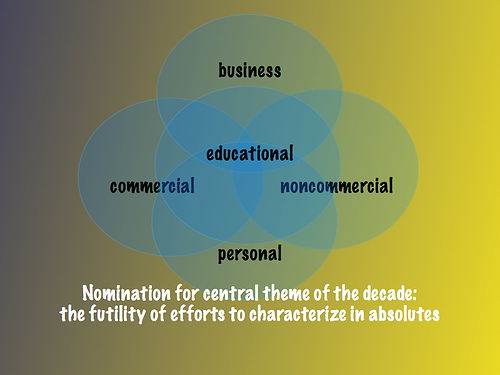

A very nuanced understanding of "private" that may be lost on judges who don't use these apps and thus feel "the Internet is public space, and that's that."

I think most judges, especially at the appellate level, will grasp the nuances, but will need to be educated carefully, perhaps with demos or screenshots showing the complex privacy controls now being offered.

It may also help to remind them that even in the familiar physical world privacy is not all-or-nothing. My (admittedly imperfect) example: I invite you to my home for a party. You use the restroom. While there, you open a closed medicine cabinet and snoop on what prescriptions I have in there. Can anyone say I gave up reasonable expectation of privacy in that information by inviting you into my home and allowing you to relieve yourself? (I admit I've never researched non-cyberspace privacy cases involving such issues.)

Indeed. The Live Web is not backward compatible with a world that assumes the mebranes around our personal and professional lives (and information) are impermeable.

For further proof, I commend to you George's whole Facebook series:

- Employers Using Facebook for Background Checking: Is It Legal?

- More on using facebook et al. in recruiting and hiring (Part II)

- More on using facebook et al. in recruiting and hiring (Part III)

[Update:] Bonus link: Your boss could own your Facebook profile