GreenDust wants Indians to be in with the old, out with the new

In India, Diwali, or the festival of lights, where a gazillion firecrackers are set off in streets, alleyways, and parks to celebrate the coming home of the god Rama after vanquishing the purportedly evil king Ravana, buying new things is a tradition, even a ritual — new clothes, perhaps a scooter or a fridge.

But in India's new consumer economy, of course, you don't really even need the excuse of Diwali to get something new. The steady traction of e-commerce companies and the proliferation of shiny new malls is ample proof of India's urge to splurge on new baubles, proof that Indians are now more than at any point in their history an important cog in the global consumer machine.

Still, this doesn't mean that used things don't command popularity in India. In fact, if anything, India is one of the most efficient recyclers of stuff, largely because of relatively large numbers of poor, some of whom become rag pickers and ensure that all the waste you carelessly throw from your house is painstakingly separated, sorted, and sold. Even hair, if you can imagine it, commands a price. (I wrote about the travails of this industry here.) If you've ever lived in an urban neighbourhood in India, you would have undoubtedly also done business with the local recycler, or "kabadiwala", who cruises around on a cycle, announcing his presence via a sonorous chant that basically says "newspaper and bottles", and will purchase all of your old newspapers and beer bottles.

However, on the whole, our experience with buying old things of larger ticket value is relatively new, and two sites that have tried to foment a revolution in Indian purchasing habits are listings sites OLX and Quickr. "We've broken some social barriers with OLX," the company's co-CEO Amarjit Singh Batra told Ndtv Gadgets.

"Earlier, people wouldn't sell things second hand. When something got old, you'd either give it to a family member or give it to a friend, or you'd let it sit and gather dust until you gave it to the kabadiwalla. The same was true about buying; there was a stigma about using used goods."

Quikr has raised a total of up to $140 million, which is a vindication of the platform-for-used-goods business model. OLX, meanwhile, is backed by the South African media company Naspers, which has also invested in companies like Flipkart, redBus, Ibibo, and others.

When I shifted houses some time ago, I got a first-hand taste for how eager we Indians are for a good second-hand deal if we can avail of it. I had decided to flog many of my appliances with the objective of getting new ones — such as my fridge, my washing machine, and my flat-screen TV, which had all provided good service for years but were now going to be upgraded — and I was shocked as to the sheer volumes of people who responded or raced to my house to put money down for them. Most paid nearly all of the asking price for each item, despite the fact that I needed to hold on to them for a month or so, as I wasn't moving until then. I could have easily decamped with their money and my goods in the middle of the month. For some reason, the trust factor here was high.

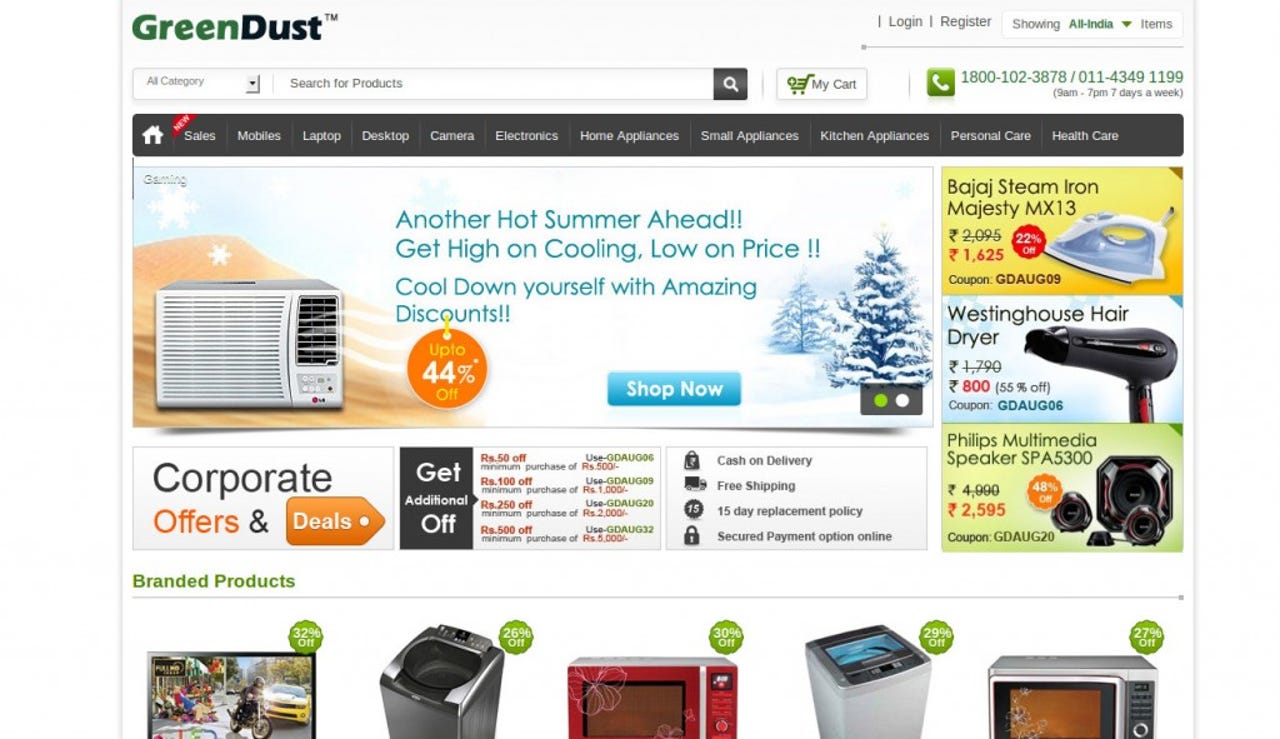

So, it's no surprise that a company like GreenDust has hit gold in its business model that buys up returned name-brand goods from retailers and e-tailers, refurbishes them, and sells them with a year's warranty to value-conscious Indians. This is done through its e-commerce portal GreenDust.com, and through its network of 170-plus franchise stores across India, which is now quickly expanding to the lucrative tier 2 and tier 3 smaller towns that have a huge pent-up demand for cheaper goods from reputed brands.

Sometimes, the unlikeliest of events, in GreenDust's case a tragedy, bring about the birth of a company. Hitendra Chaturvedi, head of Microsoft's OEM unit, returned to India to take care of his ailing father after 17 years of a working life in the US. When Chaturvedi's father passed away, he decided to stay on to look after his mother, but couldn't really find a comparable job with a comparable salary. The only viable option in his mind was going it alone and launching a business.

In this case, the industry Hitendra chose was "reverse logistics", also known as "reverse supply chain" — a term used to describe what happens to all the stuff that people return for one reason or another — an attractive business, considering 4 percent of slightly defective items get returned every year, making it a $15 billion to $16 billion opportunity. And here's the catch: At least $4 billion to $6 billion is spent bringing it back, which is a not insignificant, annoying charge that companies will be delighted to avoid.

As Chaturvedi describes in this interview to the Economic Times, companies can improve cash flow from asset recovery and working capital by injecting reconditioned merchandise into stocks, thus reducing the reliance on fresh inventory. So far, 300,000 products have been saved from the scrap heap, and a whole host of corporates including Samsung, LG, Panasonic, Philips, Toshiba, Apple, Whirlpool, and Amazon are working with the company. According to TechPanda, the company would have crossed an impressive $100 million by the end of the last fiscal year. Its business proposition was attractive enough for Vertex Venture Holdings, Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers (now Lightbox), and Sherpalo Ventures to put $40 million into it.

Of course, customer service and quality of equipment checks and upgrades over time will be the ultimate test of whether GreenDust has the chops to make it in the business, something that even the premium brands have stumbled over in India.

But for now, next time you decide to buy something new, think again. You may just as easily get it somewhere else for 70 percent of the original price.