Ground zero for credibility in blogging and journalism

This blog entry originally started as an e-mail to media academicians (ie: John Palfrey, Jay Rosen, and David Weinberger), media revolutionaries (ie: Dave Winer, Jason Calacanis, and Dan Gillmor), public relations/marketing mavens (ie: Andy Lark and Steve Rubel), and media researchers such as Forrester's Charline Li. Then I realized, why not share it with everyone.

If you didn't follow the vociferously argued debate between me and Microsoft's Robert Scoble (in our blogs) about fact checking, then you can start here and work your way back through it. But you really don't have to to get the gist of what I'm about to say. What started as a disagreement (over the how the service Technorati should be evaluated) shifted into a discussion of journalism and blogging and finally landed on an important point that really sets the stage for the next big mind meld on blogging, journalism, and credibility.

That stage might not have been set had Dave Winer not chimed in with the phrase "taking a chance." Whether he knew or not, his usage of that phrase may have pinpointed ground zero for those still struggling to articulate the difference between bloggers and journalists in the context of credibility. As many have written or implied before, these aren't two mutually exclusive realms with a portal between them that when crossed, magically changes one's credibility. Here's why.

Across the spectrum of those who think of themselves as journalists, you'll find some taking more chances than others. On the right end (appropriately so because it is ultra conservative behavior) of the spectrum are journalists that cross every single t three times, dot every single i four times, and double check every single fact they've asserted even though they may already know it to be true. They don't take any chances.

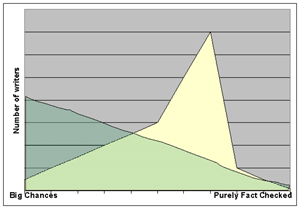

As you look left, you'll find journalists (in fact, the bulk of them) that take some chances. The more you move to the left on the spectrum, the more chances those journalists take (less and less fact checking). If the spectrum is the x-axis on a graph and the y-axis is the number of all journalists, you wouldn't see many so-called journalists at either extreme and you might see a big hump closer to the fact checking end. Likewise, based on that dialog with Robert Scoble and Dave Winer, you'd probably see the number of bloggers taking chances rise steadily as you move from right to left. With the transluscent wedge representing self-proclaimed bloggers and the beige-ish area representing self-proclaimed journalists, the graph might look something like this.

source: me (I'm positing this. It's not actual data)

A few measurements are noteworthy on this graph. First, while the number of bloggers that purely fact check their work shrinks as you move to the right, it never goes to zero. I'm guessing that there are at least some people out there that think of themselves as bloggers that take no chances. Also noteworthy is that there is no such thing as a journalist that doesn't take big chances. They exist.

Also of import is that the spectrum from purely fact checked on the right to big chances on the left is not, by itself, a guaranteed gauge of credibility (although some may use it that way). Other factors can affect credibility. For example, just because something isn't fact checked doesn't mean the writer doesn't know it to be true because of his or her expertise. But, given this information, another factor that could help gauge credibility might be a writer's agenda. While it can be argued that all writers have an agenda, I think that as you move left across the spectrum, the likelihood that you'll encounter highly agenda-driven writing (the type that draws credibility into question) goes up. If you really wanted to, you could overlay one more wedge on this graph to represent the range of writers that might have an agenda. It would start somewhere above zero way off to the right (there are plenty of heavy fact checking writers with a agenda) and grow from there as you move to the left.

You should also note that the labels "bloggers" and "journalists" are purposely left off the graph and the y-axis is simply lableled number of writers. That's because the two areas shouldn't be overlayed as they are in the above graph. They should be stacked. At the end of the day, it doesn't matter whether people think of themselves as bloggers or journalists. They're all writers, all taking chances. Some less than others. Some more than others. And, as has been proven in multiple instances -- depending on how many writers glom on -- a greater degree of chance-taking can sometimes flush out the truth in a heartbeat. Dan Rather took a chance and wasn't long before the truth was out. Whether or not a particular writer arrives at the truth through chance-taking or fact checking is not a matter of what he or she calls himself.

It's a matter of personal style and their comfort level with the chosen approach and all that goes with it (eg: impact on audience perception). When Robert Scoble decided that the time may have come to do more fact checking, he didn't go from being a blogger to a journalist. He went from being a writer that took more chances to a writer that took fewer. You'd be hard pressed to find a self-proclaimed journalist that hasn't also moved in one direction or another for whatever reasons.

This is a good time to draw the public relations community into the discussion. Much the same way writers find themselves wanting to do more or less fact checking, a lot of that has to do with how quickly we can get a response. Before recently writing a blog about how Bank of America was falling short on an advertised IT- guaranteed promise, I called the company for comment. I found a warm body to talk to and if she herself wasn't the person who could get me the answers to my questions, she clearly knew who that person was (based on my conversation). I called on a Monday. She asked if it was OK if someone got back to me on that Friday. "Um, no" I said. "I was thinking like the next 30 minutes." We were miles apart on what a reasonable time frame might be. Right now, as I write this I'm working on another blog and am trying to find out exactly what "unacceptable potential risks" Continental's free Wi-Fi access points at Boston's Logan International Airport pose to the communication gear used by the Massachusetts State Police and the Transportation Security Administration. So far, of the people I've contacted, only the State Police have gotten back to me and all they did was refer me back to MassPort (the state agency that runs the airport).

Last week, I received a letter from Siebel CRM OnDemand CRM Bruce Cleveland that was worthy of further exploration. Earlier this week, I asked Siebel's public relations folks for some of Cleveland's time. I was offered another a briefing with another executive. Next Wednesday. [Update: Now, I've been offered Monday. Accepted but still wish it was yesterday.]

Thanks to the blogosphere, on relatively short order, I went from writing twice a week to 10-15 times a week and sometimes more. There are plenty more where I came from that are feeling and responding in-kind to that same pressure. But, as the established media community picks up the pace, there are those of us in it who would prefer to keep constant the number of chances we're taking. But if the PR community doesn't also reinvent itself to keep pace with the media revolution by responding to the fact checkers on blogopshere time, it will leave those writers with no choice but to take more chances. I don't know about you, but if I were a PR professional, I sure wouldn't want to be the guy that blew that one opportunity to contain the story that snow-balled into a disaster for the company I represent.

You only get one shot, do not miss your chance to blow, this opportunity comes once in a lifetime - Eminem