Mozilla appears to abandon Firefox tracking protection initiative: Is privacy protection impossible?

Mozilla has included a feature in Firefox that can dramatically speed up web browsing. In a paper that was awarded top honors in the recent Web 2.0 Security and Privacy workshop, Mozilla researchers reported that turning this feature on dramatically improves performance on top news sites, page load times by 44 percent.

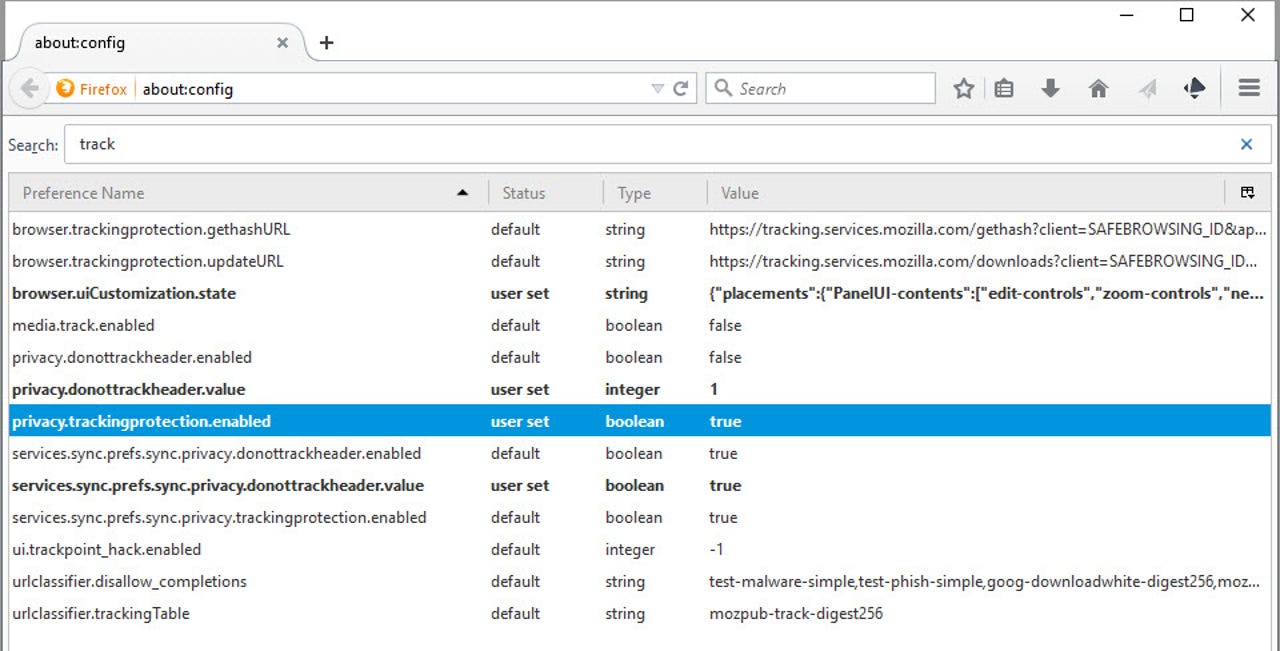

This magic feature is called tracking protection, but you won't find it exposed as an official Firefox option. Instead, it's an experimental feature that must be manually toggled on. The privacy.trackingprotection.enabled setting is in about:config, which you can only reach after clicking past the stern "You might void your warranty!" warning.

Double-click to toggle this setting to True, and any future pages you visit will refuse to connect to third-party servers identified on Mozilla's list of known tracking domains.

With tracking protection on, this badge appears in the address bar of any page you visit that contains third-party content from the block list. You can click to see whether content has been blocked and, if necessary, disable tracking protection.

Ironically, the Mozilla page that documents this feature contains content (a Google Analytics tracker) that is blocked by its own tracking protection feature.

Mozilla isn't alone in offering tracking protection. Microsoft has had a richer version of this feature in Internet Explorer since 2011, including a repository of custom, third-party Tracking Protection Lists.

There are also plenty of third-party solutions, including the one I personally use, Abine's Blur (formerly DoNotTrackMe).

Sadly, it doesn't appear that Mozilla is committed to this experimental feature. If this feature had been developed, it might include a way to identify domains that have been blocked and allow exceptions for some domains. Instead, the only way to see what's been blocked is to turn on Mozilla's Web Console and view long, inscrutable lists of warning messages.

Monica Chew, who demoed the Firefox tracking protection feature publicly for the first time last summer and was a co-author of that award-winning paper, left Mozilla in early April. Her parting shot was a blog post that contained this blunt assessment:

This paper is the last artifact of my work at Mozilla, since I left employment there at the beginning of April. I believe that Mozilla can make progress in privacy, but leadership needs to recognize that current advertising practices that enable "free" content are in direct conflict with security, privacy, stability, and performance concerns -- and that Firefox is first and foremost a user-agent, not an industry-agent.

Advertising does not make content free. It merely externalizes the costs in a way that incentivizes malicious or incompetent players to build things like Superfish, infect 1 in 20 machines with ad injection malware, and create sites that require unsafe plugins and take twice as many resources to load, quite expensive in terms of bandwidth, power, and stability.

This feature is one of two interesting privacy initiatives from Mozilla in recent years. The other is Lightbeam, which offers a visual map of trackers and offers granular control over individual trackers. Judging by its Github page, it appears to have been abandoned.

Meanwhile, the useless Do Not Track flag, which does nothing to actually prevent third-party tracking, is the only option on the Privacy tab in Firefox Options. The third-party tracking industry has neutered that standard but is happy to leave it in place to give the appearance that browsers offer some privacy protection. It's disabled by default.

The problem with tracking protection is that it is a blunt instrument trying to stop an industry that is worth many hundreds of billions of dollars and doesn't want to be slowed down in any way. Turning on tracking protection has the salutary side effect of blocking a lot of advertising, which tends to anger the big companies that pay for most of the free web.

As a result, tracking protection, regardless of the tool being used, has a tendency to break the rendering of webpages. (Here at ZDNet, for example, tracking protection software breaks the viewing of some image galleries in the site's current design and causes layout problems on other pages.)

If you're sophisticated enough to realize that tracking protection might be blocking content that is required to load a page properly, you can disable the feature as a troubleshooting measure. But if that fixes the problem, you're in the awkward position of having to decide whether to allow tracking for that site or to stop visiting.

Tracker-blocking programs could be maintained as assiduously as antimalware programs. If that had happened in recent years, we would have seen continuous improvement in Microsoft's tracking protection implementation, for example, with regular updates to the TPLs. Instead, the feature has been essentially abandoned--kept in Internet Explorer as a checklist item but not maintained at all.

Mozilla appears to be heading down the same road. The Bugzilla page for the feature hasn't had a comment in many months. It's not listed for inclusion in any of the next three Firefox releases, and there's no sign that the feature will ever become official, much less be maintained or expanded.

I've been pounding the table about privacy for years, long before Ed Snowden appeared on the scene. As far as I'm concerned, the likelihood that you and I will be bothered by the NSA is vanishingly small. We have much more to fear from shadowy corporations gathering our data and building profiles that they sell to marketers.

But effectively managing the web so that we have control over our own information is hard work and requires significant development resources. Mozilla severed its long-term partnership with Google last year, but immediately rebounded into a relationship with Yahoo. Both companies make their livelihood from selling targeted ads, which means tracking protection software is anathema.

Barring some sort of cataclysmic shift in the online economy, the status quo is likely to survive and even thrive. Privacy might be an abstract value that consumers prize, but they're not going to pay for the expensive ongoing development that effective tracking protection requires.